Since the pandemic, high levels of pupil absence have been one of the biggest challenges facing schools in England. Its impact has not been felt evenly, and it has contributed to the widening of the disadvantage gap. Last week, the Department for Education published the latest absence statistics which show that, overall, absence rates are at least falling. In this analysis, we use the latest school census data to explore whether absence has declined across the distribution or continued to rise for some absence categories, at persistent or severe levels, or for pupils with certain characteristics. Our key takeaways are:

- Overall absence rates, as well as persistent absence rates, are falling and there are signs that severe absence is starting to plateau;

- Unauthorised absences are starting to fall;

- Absence gaps are narrowing for disadvantaged pupils but are widening for those with SEND;

- Absence rates are increasing amongst the very youngest.

Overall absence rates continue to fall

Overall absence rates continued to fall in the autumn term of 2024/25 to 6.4 percent (from 6.7 per cent in autumn 2023/24 and having peaked at 7.5 per cent in autumn 2022/23. Attendance gains were particularly marked in secondary schools where post-pandemic absence challenges have been some of the greatest.

Across the country, absence remained lowest in London (5.8 per cent) and highest in the North East (6.9 per cent) but has declined across all regions compared to the previous autumn term. Despite having the lowest rates of absence overall, falls in London were relatively small and in eleven London boroughs (plus eight local authorities outside of London), the rate of absence actually increased.

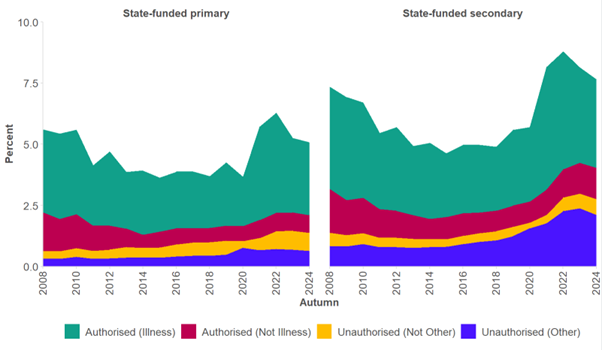

Unauthorised absences are now falling

We find that the fall in the overall absence rate is being driven not only by lower authorised absence (notably illness) but, unlike in previous years, lower ‘unauthorised other’ absence too. This is welcome and the first time this ‘catch-all’ category (often used when the reason is unknown to teachers) has fallen post-pandemic. There has been little change in most other absence types since the previous year, though the late rate has edged up (to 0.20 per cent, from 0.16 per cent in the previous autumn term) and more than trebled since pre-pandemic (0.06 per cent in 2018/19).

Figure 1: Overall absence rates over time by education phase

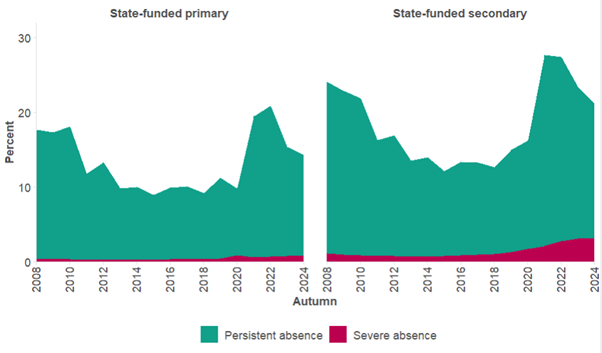

Persistent absence is falling but severe absence continues to rise

Persistent absence is defined as missing at least 10 per cent of sessions. In autumn 2024/25 the persistent absence rate was 17.8 per cent, down from 19.4 per cent in autumn 2023/24 (and having peaked at 24.2 per cent in 2022/23). Again, this is good news with decreases across both primary and secondary schools (as well as special schools), with a particularly big drop at secondary, though persistent absence remains far above pre-pandemic levels (10.9 per cent in 2018/19).

Figure 2: Persistent and severe absence rates over time, by education phase

Severe absence (missing at least half of all sessions) continues to rise – a trend that predates the pandemic and persists across all school types. The size of the severely absent group remains small – at just 2.0 percent – but it has almost trebled since pre-pandemic. We now have 148,000 pupils missing half or more of their time in school. But encouragingly, the rate of increase has slowed considerably since the previous autumn, indicating that severe absence might be approaching its peak.

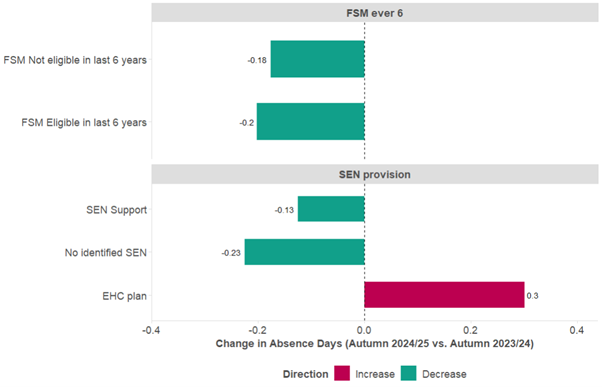

Absence gaps have narrowed for disadvantaged pupils, but widened for those with SEND

We have previously raised concerns that absence gaps continue to widen for more vulnerable groups, notably disadvantaged pupils and those with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND). The latest release shows the first green shoots for disadvantage but a deteriorating picture for SEND.

Compared with the previous autumn term, the absence gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers narrowed in autumn 2024/25, particularly at persistent levels. Based on the average number of days of absence, this fell slightly more rapidly among disadvantaged pupils (by 0.20 days to 6.6 days of absence) than non-disadvantaged pupils (by 0.18 days to 3.4 days).[1]

But SEND gaps have widened further. While absence fell among pupils on SEN support, it fell by more among those with no identified SEN, causing the SEN support gap to widen. Meanwhile absence continued to rise among those with EHCPs (from 8.4 days of absence in autumn 2023/24 to 8.7 days in autumn 2024/25) causing this gap to widen even more. And as ever with SEND data, it is worth remembering that these are the children who have received a diagnosis; there are many others with unidentified and unmet needs who remain invisible in the data and system at large.

Figure 3: Changes in the average days of absence between autumn 2023/24 and 2024/25, by pupil characteristics

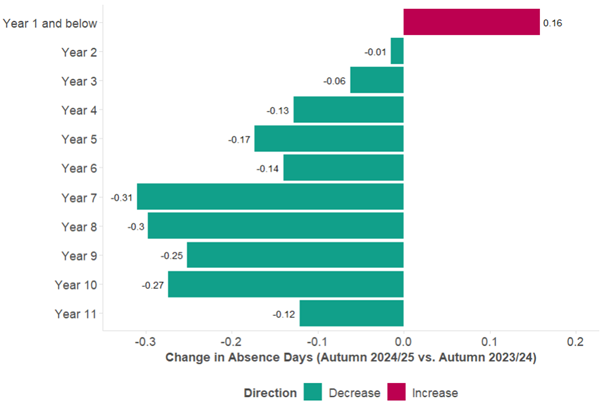

Absence rates are increasing amongst the very youngest

Absence rates tend to increase as children get older (with a step-change in absence as pupils transition from year 7 into year 8), with the most marked increases in absence post-pandemic initially seen among pupils in Year groups 9 to 11. However, the latest data reveal a concerning picture for those just starting school. Compared to the previous autumn term, the only school year group to experience an increase in absence in autumn 2024/25 was Year 1 and below, with declines for all other ages up to Year 11. Indeed, this year group was unique in seeing worsening absence across all three headline measures, including persistent and severe absence.

Figure 4: Changes in average days of absence between autumn 2023/24 and 2024/25, by year group

Conclusion

The latest absence data provides some long-awaited good news, with falling overall and persistent absence – notably at secondary school – and some early signs of plateauing in severe absence. Importantly, for the first time post-pandemic, we are seeing narrowing absence gaps for disadvantaged pupils. However, this is in the context of the overall absence rate for FSM eligible pupils remaining almost twice that of pupils not eligible, and the severe absence rate being over three and half times as high, with recent EPI research showing that higher absence among disadvantaged pupils makes a major contribution to the overall GCSE disadvantage attainment gap (of over four months to the 18.6 month gap in 2023).

More worryingly, absence continues to increase among children with more severe SEND and is not yet falling among pupils on SEN support at the same rate as their peers, meaning SEND absence gaps continue to widen.

We’re also seeing rising absence among children at the start of their school journeys, raising questions over what this means for future absence as they progress through the system and how well children in the earliest years of life are being supported to transition to school. This echoes concerns raised in our 2025 Annual Report regarding a post-pandemic widening of the early years attainment gap for disadvantaged 5 year olds and those with SEND.

It is clear that the government needs to focus on, and invest in, the early years – including increasing the rate of the early years pupil premium to match the rate in primary school – and, as part of wider SEND reforms, prioritise training in child development and different types of SEND as a mandatory part of initial teacher training and early career development.

[1] We define ‘disadvantage’ based on being eligible for free school meals at some point in the last six years