Last week we published an estimate of the effects of potential changes to fees and student loans’ conditions for graduates, public spending and universities. It was based on The Times’ speculation on the Chancellor’s plans for higher education funding. Our findings can be found on our website and on The Times Higher Education.

Following this, on the opening day of the Conservative Party Conference, Theresa May shed some light on the Government’s proposed changes to higher education funding. Although there is still a lack of policy detail, there are two changes that are now quite certain. First, tuition fees will be frozen at £9,250, which means they will not be uprated in line with inflation (as previously proposed). Second, the repayment threshold will rise from £21,000 to £25,000.

We have updated our analysis from last week to reflect these latest announcements.[1] The first scenario (baseline) is a replication of the current system: tuition fees are uprated with the inflation every year and the repayment threshold stays on £21,000 until 2020, where it will start to raise in line with annual inflation. The second scenario assumes that both the freeze on tuition fees and the new repayment threshold are introduced as early as next academic year, and that the repayment threshold increases with inflation every year. We assume that for both scenarios the interest rate remains unchanged.

Increase in public subsidy

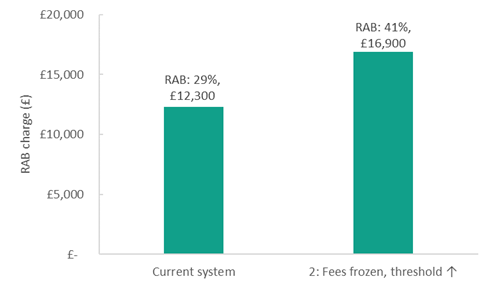

The RAB (Resource Accounting and Budgeting) charge reflects the level of public subsidy to student loans. As we suggested last week, the government currently writes off 29 per cent of all the money lent to students in the form of loans. In absolute terms, this represents £12,300 per student. The RAB charge would grow dramatically if the changes were introduced: from 29 to 41 percent, and from £12,300 to £16,900 per student. Unless actions are taken to mitigate this or cuts in other areas introduced, this could add considerable pressure to Government finances.

Figure 1. Increase in the public subsidy if tuition fees were frozen and repayment threshold raised to £25,000

Same student debt, more progressive conditions

It is noteworthy that the debt students would leave university with if fees were frozen would not differ significantly from the level they accrue now: it would only go down from £45,800 to £44,400.

In our piece last week, we stated that lowering interest rates would make the system less progressive as, under the current system, high earners are net contributors as they pay back more than they borrow. Although further changes to interest rates cannot be ruled out in the current policy environment, our alternative scenario does not contemplate any change on that front.

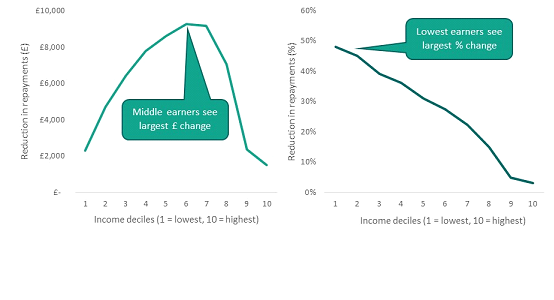

Keeping interest rates unchanged and raising the repayment threshold to £25,000 would have the opposite effect; the changes are progressive, with low and middle-income graduates benefiting from the changes the most. Figure 2 shows how much less graduates in different income deciles would pay if the threshold was raised and fees frozen compared to the current system, both in absolute (2a) and relative terms (2b). It shows that graduates in middle income deciles (5th and 6th deciles, earning £27K-£30K per annum) would be the main winners in absolute terms repaying around £9,000 less than under the current system. Whereas low and high earners would see more modest changes. However, the picture is different when considering relative terms (the percentage change in their total repayment). In this case, low earners see the largest reduction in repayments. The lowest earners (1st decile, earning £17K per annum) would repay 48 per cent less than they do under the current system. Middle earners would pay around 30 per cent less, and the highest earners (10th decile, earning £84K per annum) would only be repay 3 per cent less than under the current system.

Figure 2 – Reduction in repayments if tuition fees were frozen and repayment threshold raised to £25,000 across earning groups

2a – absolute reduction (£s) 2b relative reduction (%)

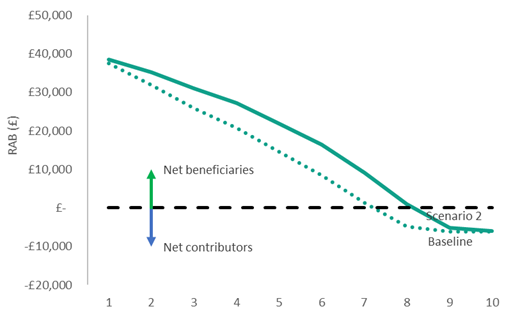

This is also reflected in the distribution of the RAB across earning groups. The additional subsidy to loans benefits middle earners more than low or high earners. Under the current model, the 30 per cent highest earners are net contributors to the system, paying back more than they borrow – by increasing the repayment threshold and freezing fees, only the top 20 per cent highest earners become net contributors.

Figure 3. Distribution of RAB in pounds per person across future earning deciles (1 = lowest earners, 10 = highest earners)

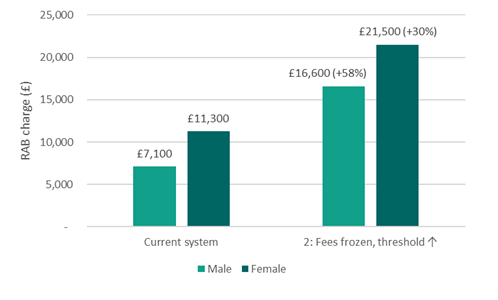

These changes would affect male and female graduates differently. Both men and women would receive more subsidy to their loans, but the increase among men would steeper. The RAB charge for male graduates would go up from £7,100 to £16,600 (an increase of 58%), while it would increase from £11,300 to £21,500 (30%) for female graduates.

Figure 4. Increase in public subsidy (RAB charge) for male and women

Conclusions

There has been widespread debate around higher education funding lately, with a lot of speculation on whether the government will amend its policy on fees and student loans. Theresa May hinted at some of the changes to come last weekend, with a lot of detail still missing. However, it is quite certain that tuition fees will be frozen at £9,250 (although the government may allow variation across subjects) and that the repayment threshold will be raised to £25,000. If these changes are implemented without any reduction of the interest rate, we should expect a more progressive system where middle earners repay a lot less in absolute terms than they do under the current system, and where lower earners see the greatest percentage reduction in the amount they pay. Nevertheless, with the public subsidy (RAB charge) increasing from 29 per cent to 41 per cent, these changes will come at a high cost for the Treasury.

Gerard Dominguez-Reig, Senior Researcher, Post-16 and Skills, Education Policy Institute

________________________________________________________________________

[1] As in our article last week, we used the BIS/DfE repayment ready-reckoner student loan repayment model to estimate the impacts of these changes. Unlike the BIS/DfE 2015 model, we have used the latest inflation and wage growth forecasts for the period 2015-2020, and have kept the long-term forecasts in place. The methodology and limitations of the approach used can be found in last week’s blog.