With the rate of university student suicides rising over the last 10 years, mental health has become a topic of increasing focus in higher education.[1] This analysis examines the prevalence of mental health issues within the student-aged population, before exploring issues affecting mental health prevalence and the barriers that may prevent students from receiving the help they need.

Prevalence of mental health issues

Sixty-four per cent of the university student population (and 83 per cent of the undergraduate population) are between 16 and 24 years old, an age group that is particularly vulnerable to mental health issues, as 75 per cent of mental health problems are established by the age of 25.[2] Data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey shows an increase in the prevalence of common mental disorders (CMDs) for 16- to 24-year-olds, indicating that today’s young adults are more likely to experience mental illness than previous generations. In England, the proportion of 16- to 24-year-olds experiencing a CMD rose from 15 to 19 percent between 1993 and 2014, representing an increase of over 25 per cent.

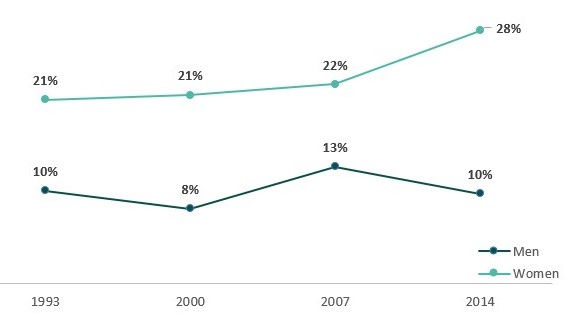

Figure 1 shows that this increase is mainly driven by women, who are almost three times more likely to experience a CMD than men. Between 1993 and 2014, the proportion of 16- to 24-year-old women experiencing a CMD increased by 38 per cent, compared with a decrease of three percent for 16- to 24-year-old men.

Figure 1: Diagnosed CMD experienced in the past week in 1993, 2000, 2007 and 2014, by sex[3]

The extent to which younger adults (16- to 24-year-olds) are more likely to experience mental health issues than older adults (25- to 54-year-olds) is unclear: although CMDs were slightly more prevalent in older adults, the rise in the proportion of younger adults experiencing a CMD between 1993 and 2014 was sharper than the rise for older adults. In addition, younger adults are more likely to have suicidal thoughts, attempt suicide, and self-harm than older adults.

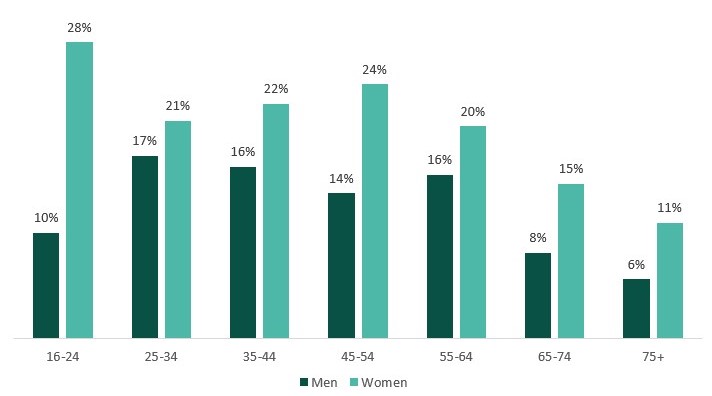

However, there is a disparity by sex when comparing CMD prevalence in younger and older adults. In 2014, the proportion of 16- to 24-year-old women who experienced a CMD was higher than the proportion of women in all other age groups. Women in this age group were also approximately one and a half times more likely to have suicidal thoughts or attempt suicide, and almost three times more likely to self-harm than all women on average. Conversely, 16- to 24-year-old men were among the least likely to experience a CMD, with lower rates occurring only in men aged 65 and above. They were also no more likely to have suicidal thoughts and attempt suicide than men in other age groups.

Figure 2: Diagnosed CMD experienced in the past week by age and sex[4]

For students in higher education specifically, there is also evidence of increasing levels of reported mental health issues. The proportion of UK-domiciled first-year students at higher education institutions (HEIs) who disclosed a mental health condition in 2015/16 was two per cent, five times the proportion in 2006/07.[5] Furthermore, a survey conducted by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) revealed that the demand for counselling services has increased significantly. Ninety-five per cent of HEIs reported an increase in the demand for counselling services, and for 61 per cent of HEIs this increase was greater than 25 per cent.[6]

Suicide in higher education

It is true that the mental health prevalence trends discussed above may reflect an increase in disclosure due to greater public awareness and reduced stigma surrounding mental health conditions, rather than an actual increase in prevalence. However, student suicide rates have also increased by 52 per cent since 2000/01, reaching 4.7 per 100,000 of the population in 2016/17. Given the strong link between suicide and mental health issues (over 90 per cent of suicides and suicide attempts are associated with a psychiatric disorder), the increasing suicide rate indicates that both disclosure and prevalence of mental health issues are on the rise.[7]

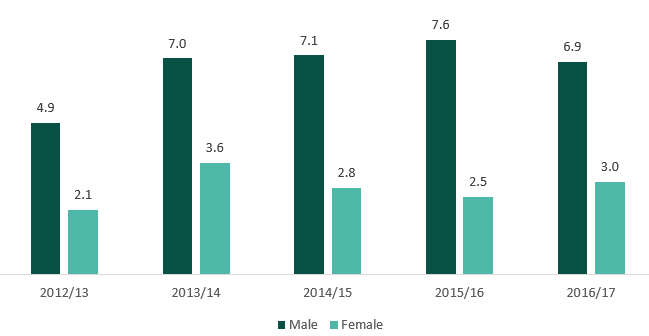

Looking into variations by sex, we notice that men are at the greatest risk of suicide. Despite being almost three times less likely to report experiencing a CMD, suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts, male students were more than twice as likely to die by suicide than female students between 2012/13 and 2016/17.[8] This suggests that the gender gap in the prevalence of CMDs may be partly attributed to men being more likely to underreport their mental health difficulties, rather than representing a true difference in CMD prevalence between men and women.

Figure 3: Rate of suicide among higher education students in England and Wales, by sex.[9]

Students over the age of 25 were overrepresented among undergraduate students who died by suicide: they accounted for 46 per cent of undergraduate student suicides in 2016/17, despite only accounting for 31 per cent of the undergraduate student population, while students aged 24 and younger accounted for 54 per cent of suicides in 2016/17.[10]

Possible factors affecting student mental health

Changing demographics in higher education may partially account for the higher prevalence of mental health issues. The number of young people from disadvantaged backgrounds in higher education has increased over the last five years. Three of the indicators used by the Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA) to measure widening participation are the state school marker, low participation neighbourhoods and parental education. Between 2012/13 and 2016/17, the number of higher education students:

- from a low participation neighbourhood increased by 13 per cent;

- whose parents did not attend university increased by 23 per cent;

- from a state-funded school or college increased by nine per cent.[11]

While mental health issues can affect individuals in all socio-economic groups, being from a more socially disadvantaged background is associated with a substantially higher risk of experiencing a CMD.[12]

In addition, financial and academic stressors associated with university life may have a negative impact on mental health. Research has linked high financial concerns with poor student mental health, suggesting that increasing financial concerns may provide a partial explanation for the rise in mental health issues in higher education students.[13],[14]

Today’s students are faced with larger debts than previous generations, particularly in light of the rise in tuition fees and the abolition of maintenance grants. The 2018 repayment cohort had an average loan balance of £34,800 upon entry into repayment.[15] This is almost twice the average loan balance of the 2013 repayment cohort and more than three times the loan balance 2008 repayment cohort, reflecting the escalating costs associated with higher education.[16] In a Unite Students survey, 41 per cent of students reported feeling very or fairly concerned about being able to repay their loans, with this figure rising to 48 per cent for students from the lowest socio-economic group.[17] However, it is important to note that these concerns may reflect students’ perception of their loans rather than the reality of the student finance system: loan repayments are income-contingent, and three-quarters of graduates will never fully repay their student loans.[18]

There is also some evidence to suggest that students feel financially strained as they manage their own finances for what is often the first time. A poll conducted by HSBC found that one fifth of students spent all of their student loan within the first 100 days, with the average student spending almost three fifths of their loan in this time period.[19] Over 60 per cent of the students surveyed by Save the Student did not think that their maintenance loan was enough to live on, and 46 per cent reported that these financial difficulties negatively impacted their mental health.[20]

The academic demands of university life may also be a significant source of stress. In the Unite Students survey, 71 per cent of respondents reported that ‘performing well in tests and coursework’ caused them stress, and 65 per cent felt stressed trying to keep up with their studies.[21] ‘Study’ was also found to be the primary stressor among university students in a YouGov survey, as reported by 71 per cent of students.[22]

It is unclear whether academic demands are a greater source of stress among higher education students today compared to older cohorts – however it is true that the graduate job market has become more competitive as the number of graduate roles has failed to keep up with the growing supply of graduates. In the third quarter of 2017, 49 per cent of all recent graduates were working in non-graduate roles, representing an increase of 10 percentage points since 2001.[23] The YouGov survey reported that 39 per cent of students stated that finding a job made university life more stressful, making it second highest cause of stress after study.[24] In addition, for around 70 per cent of graduate employers, the minimum entry requirement is an upper second-class honours degree, placing further stress on students who may feel the pressure to achieve top marks if they want to succeed in the current market.[25]

Stress alone is not diagnosable mental illness, but excessive, poorly managed, and prolonged stress can have a detrimental impact on psychological health and can subsequently lead to common mental health issues such as depression and anxiety.[26]

Treatment barriers for students in higher education

Most mental illnesses manifest at a young age, and the stress faced by university students may have a further negative impact on their mental health. Yet, 16- to 24-year-olds are least likely to receive any form of treatment for their mental illness, regardless of the severity of their symptoms.[27] Furthermore, the Equality Challenge Unit (ECU) found that around one half of student respondents who had experienced mental health difficulties during their time at university had not received any therapeutic support, adjustments to course assessment, or other forms of academic/mental health support provided by universities.[28]

In part, this could represent an unwillingness to disclose a mental illness or seek help due to the stigma that still surrounds the topic. In a Student Minds survey identifying 93 challenges facing student mental health, students ranked fear of being judged as the biggest challenge and the idea that mental health issues are seen as a weakness as the fourth biggest.[29] An ECU survey reported similar findings. Of those who did not disclose their mental health issues or seek treatment, two of the main reasons that they gave for this were not wanting other students to think less of them and fearing ‘unfair treatment’ from their institution as a result of their illness.[30]

The remaining stigma surrounding mental illness is important for universities to address. Worryingly, those who do not disclose may be more predisposed to suicide, as only 25 per cent of those who died by suicide were in touch with mental health facilities at the time of their death.[31] The stigma surrounding mental health issues in men in particular should be addressed, since they are three times less likely to disclose a mental health issue but twice as likely to die by suicide than women.[32]

The beginning of university is a time of transition for students, which can also be a barrier to them receiving mental health treatment. They often move away from home and leave behind their regular GP and support system, making it more difficult to receive consistent and timely care. University mental health advisors and other healthcare professionals reported that the biggest challenge facing student mental health is that ‘the NHS is not set up to support students as they move between home and university.’[33] Students are currently unable to register with two GPs. If they are already in contact with mental health services before starting at university, it may take a while for the student’s notes and treatment plans to be transferred to a practice closer to where they study. In addition, when they return home, especially for longer periods of time over the summer, their notes and treatment plans are often inaccessible, raising significant issues for continuity of care.

Starting university can also coincide with the age at which many students would be transitioned from child to adult mental health services, which is typically age 18 but can vary by provider. Dr Jacqueline Cornish, NHS England’s National Clinical Director for Children, Young People, and Transition to Adulthood, has admitted that, in general, transitions are ‘poorly planned, poorly executed, and poorly experienced.’[34] This presents a real risk that vulnerable young people will disengage or become lost during the process, which would create more problems for the continuity of care that they receive.

To make sure that young people receive the help they need, policymakers should address the barriers that prevent or disrupt treatment at a time where students are already vulnerable, especially given the new pressures faced as they transition into higher education.