Does moving schools from one academy trust to another improve performance? Jon Andrews looks at the latest evidence.

While it may have seemed that the debate about school structures had moved on, Angela Rayner’s speech to the Labour Party conference, [1] and the uncharacteristically strong response from the Secretary of State himself [2] mean that we are back on a fairly familiar battleground.

So, let us return to the evidence.

Neither full academisation nor a wholesale return to local authority oversight of schools is supported by the data. The Education Policy Institute has now published several reports that show that, when taken in aggregate, there is little difference in the performance of academies and local authority maintained schools. A big push in either direction would be likely to create a lot of work for DfE, and yet more turbulence in the system, but would be unlikely to increase standards.

What we do know is that some academy trusts are performing better than others, and schools in some local authorities are performing better than in others. Our latest league tables show that for pupils, the difference between being in a high or a low performing school group is equivalent to around half a grade in each of their GCSE subjects. [3]

Proponents of the academy system argue that one of its strengths is that it provides the option to shut down poorly performing academy trusts and move schools to ones that are more likely to help improve results. A process commonly known as ‘re-brokerage’.

In our report we argued that this should also include the option to move schools back to the local authority, if that authority is itself high performing. One of the main reasons for that is simply one of capacity in the system. The argument behind moving schools between academy trusts relies on an assumption that schools can be moved on, and hopefully quickly. We know that in many cases that has simply not happened, with schools being left ‘in limbo’ for months on end. [4]

Such delays can be caused by a lack of local capacity or because there can be disincentives for trusts to take on some of the most challenging cases. The Regional Schools Commissioner may decide that it is better to wait, and build that capacity in the right place, rather than rush to move a school between trusts and risk that school having to be moved again in future. But these delays can cause a great deal of uncertainty within the school and within the local community. It risks the school facing falling rolls – with knock on effects for school funding – and struggling to recruit and retain teachers. Anything that can help mitigate against these risks should be welcomed.

And while the principle of re-brokerage sounds fine in theory there has to date been little analysis of the impact of these moves on pupil outcomes, yet these moves are becoming an increasingly important feature of our school system.

Analysis published by the Department for Education shows that between 2013-14 and 2016-17, 332 academies moved between academy trusts.[5] These moves may have happened for a number of reasons, it is not just because a trust has closed down. For example:

- a voluntary move, for example a stand-alone academy moving because they want to join a MAT;

- moving one or more academies from a trust due to performance issues with those individual academies; or

- moving one or more academies from a trust due to capacity issues with the trust (for example, to allow the trust to focus on improving standards across a smaller number of schools).

As a first step in understanding the impact of these moves, we have looked at the Progress 8 scores of these academies.

We matched data from DfE’s provisional performance tables for 2018 with the published list of academies that have moved schools. [6] In total, we were able to identify 162 academies that had a published Progress 8 score and that had moved trusts between 2013-14 and 2016-17.

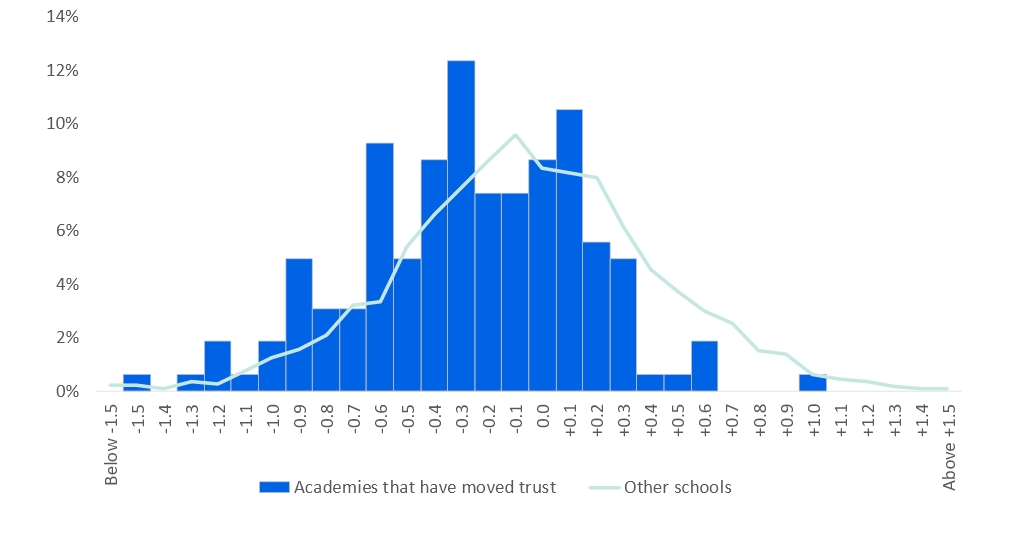

We began by looking at simple averages. We found that schools that have moved trusts tend to achieve lower outcomes than other schools and are less likely to be amongst the highest performing schools (Figure 1). The group of schools that have moved trust at some point achieved an average Progress 8 score of -0.2, meaning that they achieve around a fifth of a grade lower than pupils with similar prior attainment nationally.

This result is far from surprising and can certainly not be taken as a reflection on the effectiveness of the re-brokerage policy. In a lot of cases, academies were moved precisely because they were underperforming so it is not surprising to see that they have results that are below average – in the same way that we would not judge the overall effectiveness of sponsored academies by their headline results, at least not initially (they are sponsored academies because they are poorly performing, not the other way round.)

Figure 1: Distribution of Progress 8 scores for academies that had moved trusts and other state-funded mainstream schools (including academies that had not moved trusts). (Click to enlarge).

To explore this further we then tracked the performance over time of schools that had moved trusts. This is not without difficulty. Progress 8 is only in its third year and is not a measure that can meaningfully be applied retrospectively (since it is heavily influenced by curriculum choices). In our latest academies report we constructed a ‘best 5’ GCSEs progress measure – outcomes in English, mathematics and three other GCSEs – to have something that was aligned to Progress 8 but without being so distorted by changes to the subjects that students were taking. We have used that here to provide a longer time series of outcomes. It is still not perfect, not least because we are also dealing with qualifications that have themselves changed over this time, particularly the move to the new 9-1 scale.

In Figure 2 we group schools that have moved trust by academic year and track their results over time, we highlight when the results apply to the new trust. [7]

Figure 2: Distribution of progress scores over time for academies that had moved trusts to illustrate pre and post move outcomes, including comparison to other state-funded mainstream schools (click to enlarge).

As a note of caution when interpreting these results. We would normally expect schools with very low results to move closer to average over time regardless of any intervention. This is commonly seen in school results and is an effect known as regression to the mean. We are also not controlling for other factors such as whether the composition of schools has changed over time.

Keeping in mind those caveats, there are a few things we can see in this analysis.

Firstly, schools that moved trusts four years ago (having results published for the first time in 2014/15) do appear to now be performing, on average, better than they did at that point. In fact, there is a clear shift in the part of the performance distribution that they now occupy. Now, this group is relatively small and there are some schools with very low results (small numbers make extreme results more visible), but outcomes for these pupils are now better than they were five years ago.

There were also improvements in the ‘2015/16’ group and these appear to have been sustained. However, these improvements began prior to moving trusts and so do not appear to be directly related to moving (in any of this we cannot see where a trust was working with a school prior to them officially joining the trust but in this instance the improvement appears to have happened over a relatively long time period so this is less likely).

Secondly, for more recent movers we have not yet seen a real shift in results, though these schools did not tend to have such low results prior to moving trust. In the case of the ‘2017/18’ group there had been a steady decline in average outcomes in recent years, which at least appears to have been arrested post move. We will need to see what way the trend goes from now on.

Finally, at aggregate level at least, there does not appear to be any negative ‘shock’ to the school in the year that it moves trust (i.e. it does not appear to result in a significant dip in results due to any turbulence within the school). This is something though that really does require further exploration, not only in terms of outcomes but what a move means for pupil intakes and the teacher workforce.

So overall, while at this stage our analysis is fairly crude and we are reluctant to draw too many firm conclusions, there are indications that moving schools between trusts does appear to be associated with some positive outcomes and we may see further improvements over time. As ever it is a bit of a mixed picture and some schools continue to achieve the same results that they did before with some being particularly low. A more detailed analysis is needed before we are able to draw a causal link between re-brokerage and improving outcomes, particularly as schools with low outcomes tend to achieve the greatest improvements regardless of intervention

What we can say with confidence, is that tracking the performance of these schools will become increasingly important in the debate around the performance of the system as a whole.

Findings from this paper also feature in an article for Schools Week. You can read it here.

[1] Schools Week, ‘Angela Rayner: full text of Labour party conference 2018 speech’ https://schoolsweek.co.uk/labour-party-conference-angela-rayners-speech/

[2] Schools Week, ‘Leave our kids alone, Hinds to tell Labour in speech’

https://schoolsweek.co.uk/leave-our-kids-alone-hinds-to-tell-labour-in-speech/

[3] J. Andrews (2018), ‘School performance in academy chains and local authorities 2017’, June 2018

https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/performance-academy-local-authorities-2017/

[4] Schools Week, ‘Sponsors found for eight of the 12 Education Fellowship Trust schools’, March 2018 https://schoolsweek.co.uk/sponsors-found-for-eight-of-the-12-education-fellowship-trust-schools/

[5] DfE (2017), ‘Academy trust transfers and grant funding’, September 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/academy-trust-transfers-and-grant-funding

[6] As an additional match we used the ‘links’ data from Get Information About Schools to allow for cases where schools had changed their unique identifier (URN) at some stage. https://get-information-schools.service.gov.uk/

[7] Consistent with DfE measures we say that the results apply to the new trust if they are with the trust in September of that academic year