Executive Summary

Context

Following widespread pandemic disruption during 2020 and 2021, 2022 saw the return of summer exams. During the pandemic years, pupils’ grades were awarded using alternative processes known as centre assessed grades (CAGs) and teacher assessed grades (TAGs), whilst statutory assessments were cancelled altogether at earlier key stages. As part of the transition back to exams in 2022, adaptations were made to exams and overall results were set broadly at a mid-point between (the higher grades of) 2021 and 2019, with 2022 marking a staging post back to pre-pandemic grading.

Although the immediate disruption of the pandemic on learning and assessments has passed, this analysis considers the longer-lasting impacts of the pandemic on attainment gaps for cohorts aged 5, 11 and 16, as well as those at the end of 16-19 study in 2022. Given the unprecedented change in the way results were awarded in 2020 and 2021, we compare 2022 results with those of 2019 when exams were last sat.

In our October publication, we explored attainment gaps at a national level for key characteristics relating to disadvantage (including those in long-term poverty), special educational needs and disabilities, and ethnicity. In this release, we additionally consider attainment gaps by gender, for pupils with English as an additional language, gaps for students in the 16-19 phase of education, and subnational disadvantage gaps across all phases. Newer findings and proposals are shown here with (new).

Unlike for earlier phases, gaps shown for the 16-19 phase are shown in grades rather than months as the underpinning assumptions for our month methodology do not extend to the 16-19 stage. Also, the results for the 16-19 phase will include qualifications assessed under CAGs and TAG, as many 16-19 study programmes consist of smaller qualifications taken throughout 16-19 study, or courses which have a modular assessment structure.

Disadvantage

In 2019, the year before the pandemic, progress in closing the gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers had already started to stall. We had seen signs of the gap starting to widen in the early years and secondary phases, but 2019 also saw worrying signs emerge in the primary phase.

The pandemic then accelerated that trend and, between 2019 and 2022, we have seen the disadvantage gap widen across all phases of education. The attainment gap is even wider for persistently disadvantaged pupils (those eligible for free school meals for at least 80 per cent of their time at school).

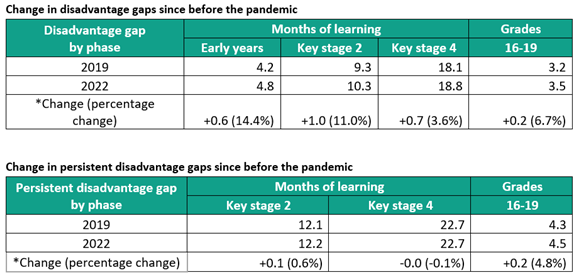

The tables below show how the gap has widened across all compulsory educational phases since 2019.

- At age 5, disadvantaged pupils were 4.8 months behind their peers in 2022, a wider gap than in 2019 (4.2 months) and its highest level since 2014 (when it was 4.9 months).

- By the end of primary school (key stage 2), the disadvantage gap was 10.3 months – one month wider than in 2019 and higher than its 2012 level. This has reversed a sustained period of decreasing inequalities between 2011 and 2018.

- By the end of secondary school (key stage 4), disadvantaged pupils were over 18.8 months behind their peers. This gap has widened since 2019 (by 0.7 months) to reach its highest level since 2012.

- Persistently disadvantaged pupils were around one year (12.2 months) behind their non-disadvantaged peers by the end of primary school and almost two years (22.7 months) behind by the end of secondary school. And counter to the trend for all disadvantaged pupils, there has been no progress in closing the gap for this group over the last decade or so.

- Whilst the raw data suggests that the gap for persistently disadvantaged pupils has not changed since 2019, when we adjust this for changes in the composition of those eligible for free school meals (due to Universal Credit ‘transitional protections’), there is some evidence that gap for persistently disadvantaged pupils has, indeed, widened since 2019.

- (new) Disadvantaged 16-19 year olds were 3.5 grades behind their peers across their best three subjects in 2022. This is the widest this gap has been in comparable years since our time series began in 2017, and compares to 3.2 grades difference in 2019, just before the pandemic.

- (new) The 16-19 disadvantage gap was wider still for persistently disadvantaged students, who were 4.5 grades behind their peers.

- (new) Differences in the qualifications that students from different backgrounds entered was a key driver of the overall 16-19 disadvantage gap widening during the pandemic, as those taking A levels tended to benefit from more generous grading compared with those taking Applied General qualifications. The grading approach in 2022, which preserved some of these differences, is likely to be one factor resulting in the 16-19 disadvantage gap remaining wider now than it was in 2019.

Gender (new)

Girls outperform boys across education phases but unlike other characteristic breakdowns, the gender gap is unique in narrowing during the primary school phase – before widening again during secondary school. The gender gaps we find are not unique to the English education system and point to common challenges in supporting boys’ literacy outcomes. The 2022 data finds that:

- Among reception-aged pupils: girls were already 3.2 months ahead of boys, an increase from 2.9 months in 2019 (although this gap is still nearly one month narrower than in 2013). Girls consistently outperform boys in all key learning areas but historically, this is most marked for literacy (especially writing) and least marked for maths.

- By the end of key stage 2: girls were 2.1 months ahead of boys, a decrease from 2.4 months in 2019 and similar to the 2011 gap of 2.0 months. Looking at reading and maths separately, girls were 5.5 months ahead in reading in 2022, whereas boys were 2.0 months ahead in maths. This means boys overtake girls in maths during primary school.

- By the end of key stage 4: girls were 5.0 months ahead of boys, averaged across GCSE English and maths – a narrowing from 6.3 months in 2019 and marking the smallest gender gap since the start of the series in 2011. Girls were almost 10 months ahead in GCSE English – a much larger gap than the one for reading at the end of primary school (of 5.5 months), whilst the gap for GCSE maths was negligible (at 0.4 months). This indicates that over the course of secondary school, girls pull further away in English and fully catch-up with boys in maths.

- In the 16-19 phase: female students have consistently achieved higher grades than male students, but this gap has widened since before the pandemic. In 2022, female students were 1.8 grades ahead of male students over their best three qualifications, compared to 1.6 grades in 2019.

English as an additional language (new)

Attainment varies significantly by first language and pupils arriving late to the English state school system with English as an additional language (EAL) incur a significant attainment penalty. This is broadly similar in magnitude to economic disadvantage, yet there is almost no policy focus on EAL in England. We are not able to identify late arriving EAL students in the 16-19 phase. The 2022 data finds that:

- Children with EAL in reception year were 1.9 months behind their peers – a similar sized gap to 2019 (1.8 months) but a long-term reduction of over one month since 2013.

- By the end of primary school, pupils with EAL who arrived late to the state school system were almost one year (11.6 months) behind their peers. This is a significant reduction on the 2019 gap (15.5 months) and marks a faster rate of progress in gap-narrowing than over the pre-pandemic period 2011-2019. Most (60 per cent) of this gap-narrowing during 2019-2022 reflects compositional shifts within the EAL group towards historically high-attaining ethnic groups (including unprecedented growth in the number of Chinese pupils with EAL over this period) and away from lower-attaining ones.

- By the end of secondary school, late-arriving pupils with EAL were 16.6 months behind their peers. As with key stage 2, this is a marked reduction on the 2019 gap of around 4 months. It reverses the trend of widening inequalities at GCSE for late-arriving EAL pupils in the years leading up to, and during, the pandemic. The marked gap-narrowing during 2019-2022 again at least partly reflects compositional shifts within the EAL group, towards Chinese and Indian pupils and away from Gypsy Roma pupils.

Special educational needs and disabilities

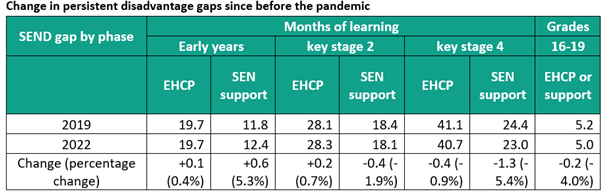

Children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) are significantly educationally disadvantaged and have some of the largest attainment gaps. The impact of the pandemic has been mixed for SEND learners depending on their age and level of need. Over the last decade or so, there has been better progress in gap-narrowing for older pupils than for those starting school, as well as for those with less significant needs. The 2022 data finds:

- Among reception-aged pupils: those with an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) were7 months behind their peers and pupils receiving SEN Support were 12.4 months behind. These gaps have flatlined and widened respectively during the pandemic and, unlike for later phases, they have also widened since the start of the series in 2013.

- Among pupils at the end of key stage 2: those with an EHCP were 28.3 months behind their peers, while those receiving SEN Support were 18.1 months behind. These gaps have narrowed overall since 2011 but with slower progress in recent years – and for the EHCP group, progress has gone into reverse, with this gap widening since 2016, including during the pandemic period.

- Among pupils at the end of key stage 4: those with an EHCP were well over three years (40.7 months) behind their peers, while those receiving SEN Support were almost two years (23.0 months) behind. Both gaps have narrowed over the course of the pandemic, continuing the longer-term trend of gap-narrowing since 2011 – indeed the gap among pupils aged 16 receiving SEN Support was almost six months smaller than in 2011.

- (new) There has been some progress in closing the 16-19 SEND gap since before the pandemic. In 2022, students with an identified special educational need or disability were around five grades behind other students, compared to 5.2 grades in 2019 and 5.5 grades in 2017.

Ethnicity

Attainment varies significantly between ethnic groups and many ethnic groups improve their position relative to White British pupils – the largest ethnic group – as they progress through schooling. The attainment of White British pupils has also declined relative to most other ethnic groups in the wake of the pandemic.

- At age 5, only four ethnic groups were ahead of White British pupils in 2022: Chinese, White Irish, White and Asian, and Indian pupils. These gaps are small at under two months, though have generally widened since 2019. The lowest attaining ethnic groups at age 5 were Gypsy Roma pupils (who were 8.6 months behind White British pupils in 2022) and Irish Traveller pupils (7.9 months behind).

- By the end of primary school, Chinese pupils were 10.7 months ahead of White British pupils and Indian pupils 8.8 months ahead. The lowest attaining groups at the end of primary school remained Gypsy Roma (19.2 months behind White British pupils in 2022) and Irish Traveller pupils (18.2 months behind). Between 2019 and 2022, most ethnic groups narrowed the gap relative to White British pupils at the end of key stage 2, except for White and Black Caribbean and Irish Traveller pupils whose gaps both widened.

- By the end of secondary school, Chinese pupils were a full two years (24.1 months) ahead of White British pupils whilst Gypsy Roma pupils were over 2.5 years (31.4 months) behind. Between 2019 and 2022, higher-attaining ethnic groups at GCSE have pulled further away from White British pupils and lower-attaining groups have generally narrowed the gap, with the exception of White and Black Caribbean pupils.

- (new) In the 16-19 phase all ethnic groups which had average attainment greater than that of White British students in 2019, had extended this lead further by 2022. The ethnic groups with the biggest grade increases over this period were those from Any Other Asian Background, Chinese students and Indian students. Black Caribbean, as well as White and Black Caribbean, students fell further behind White British students between 2019 and 2022.

Geography (new)

This report includes new interactive geographic tools for understanding how disadvantage gaps vary across England. For all phases and levels of geography, we compare the attainment of disadvantaged pupils locally to the attainment of non-disadvantaged pupils nationally. The 2022 data finds that:

- Disadvantaged pupils in London continue to pull away from other areas in England across education phases. In London, the disadvantaged gap was 3.4 months at age 5, 6.3 months by age 11 and 10.0 months by age 16. The West Midlands also stands out as the region with the second smallest disadvantage gaps across all school phases.

- The regions with the largest disadvantage gap at each phase were the North West at age 5, the South West at age 11, and the South East at age 16, whilst both the South East’s and North East’s relative rankings declined between the ages of 5 and 16.

- At a local authority level, Newham is notable in its success in consistently achieving the smallest disadvantage gap at the end of primary and secondary school (1.2 and 3.8 months respectively). Slough also distinguishes itself as having one of the smallest gaps across phases outside of London. In the 16-19 phase Southwark had the smallest gap, with disadvantaged students actually ahead of the national average for non-disadvantaged students by 2 grades.

- By the end of secondary school, there are particularly large disadvantage gaps in Torbay (27.7 months), Kingston-upon-Hull (26.7 months) and Blackpool (26.6 months), whilst recognising that Kingston-upon-Hull and Blackpool are also among the fifth most deprived local authorities in England.

- Whilst no local authority had a smaller gap for pupils aged 16 than pupils aged 11, some London authorities have increases of under one month, namely: Westminster, Ealing, Hounslow, Wandsworth and Hillingdon. At the other extreme, the biggest increases over the course of secondary school occurred in Blackpool (with a gap-widening of 18.7 months between the ages of 11 and 16), Torbay (+18.4 months) and Kingston-upon-Hull (+17.6 months).

- Looking across the full period of schooling from ages 5 to 16, it is remarkable that the gap increases by less than 2 months over 11 years of schooling in Tower Hamlets, Westminster, Redbridge and Newham. Indeed, the twenty local authorities with the smallest total gap-widening over the course of primary and secondary schooling are all in London. The three local authorities with the biggest gap-widening across school phases are Kingston-upon-Hull, Torbay and Blackpool.

- There are some signs of promise from the government’s flagship Opportunity Area (OA) programme (notably during the primary phase), though only one OA (Oldham) has managed to narrow its disadvantage gap across all phases between 2016 and 2022.

- In our previous annual reports, we have shown the importance of persistent poverty as a driver of the disadvantage gap both nationally and regionally. In this report, we do not provide further analysis of how persistent poverty affects subnational disadvantage gaps (although it undoubtedly does). This is because Universal Credit not only complicates what is happening to the persistently disadvantaged group over time, its effects will not be evenly felt across the country due to it being rolled out to different places at different times.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

The pandemic continues to cast a long shadow over the attainment of children whose educational experiences were disrupted several years earlier or, in the case of reception children, during their earliest years at home. However, this shadow was not cast equally across all groups of children, with some of the country’s most vulnerable children falling further behind their peers since 2019.

But educational inequalities existed before the pandemic. In many cases, the patterns of the last few years continue a long-term trend where progress in gap-narrowing had ground to a halt – or even started to reverse. With the pandemic generally exacerbating these trends, policymakers now face an even greater challenge that has concerning implications for social mobility in England.

Yet widening attainment gaps do not have to be inevitable, demonstrated by the generally good progress in reducing attainment gaps during the earlier period of 2011-2015, as well as the rapid catch-up achieved by some minority groups as they progress through their schooling.

Our latest recommendations for policymakers are as follows:

- (new) Given the common challenges across developed countries in supporting boys’ literacy outcomes, the Department for Education should explore international evidence on best practice from nations that have secured high quality educational outcomes whilst limiting gender gaps.

- (new) In addition to the basic EAL funding factor in the national funding formula for EAL pupils during their first three years in school in England, the government should introduce a ‘late arrival’ premium for schools to provide intensive support to address the large attainment penalties for pupils with EAL who arrive late during the primary or secondary phases.

- (new) To inform a coherent EAL policy, the government should improve official data on this highly diverse group of pupils. This should include a reintroduction of mandatory assessment and national data collection of English language proficiency for pupils who speak EAL (to help schools monitor the progress of EAL learners through the curriculum and align with the data collected in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland), and publishing pupil attainment data broken down by time of arrival, first language, ethnicity, and ideally, proficiency in English.

- (new) Now that the programme has concluded, the government should publish an impact evaluation of the Opportunity Area programme and use this to inform policy development on place-based approaches to tackling social mobility, including the future direction of the Education Investment Area programme.

- (new) The government should introduce a student premium in the 16-19 phase, akin to the pupil premium at key stage 4. This additional funding should be weighted towards persistently disadvantaged students, as our evidence shows they suffer even greater educational challenges. Detailed thinking about the level the premium should be set at, how it should interact with other funding, and accountability arrangements will be needed if such a policy is to be implemented successfully. EPI will be conducting further research to inform these considerations during 2024.

Our previously published recommendations for policymakers in relation to disadvantaged and other vulnerable learners are as follows:

- The Department for Education (DfE) should publish a strategy setting out how it will reduce the disadvantage gap in the wake of the pandemic. This strategy should clarify the government’s level of ambition regarding educational inequalities, should assess the effectiveness of existing policies aimed at reducing disadvantage, and should set out a pathway to implementation based on the best available evidence.

- There is also an urgent need for a cross-government child poverty strategy which recognises that the social determinants of educational inequalities – such as poverty, housing, healthcare, transport and many other aspects of daily life – cannot be addressed by schools in isolation or even any one government department.

- There should be higher levels of funding for disadvantage, which is then weighted more heavily towards persistently disadvantaged pupils. These pupils are now almost two years behind non-disadvantaged pupils, and four additional months behind the wider group of all disadvantaged pupils, by the time they take their GCSEs.

- To target this additional support, the DfE should ensure persistently disadvantaged pupils can be easily identified by schools. Including these identifiers on the National Pupil Database will additionally support research on the outcomes of these pupils. The DfE should also make available centrally held data linking family income to pupil-level attainment, given that Universal Credit protections will continue to affect who is considered disadvantaged based on FSM eligibility.

- There needs to be more effective support for the very youngest children with SEND and for all children with the most significant SEND, as there has been no progress in closing the gap for these groups in recent years. We have previously recommended better teacher training, reviewing the high needs budget, ensuring access to other professionals such as educational psychologists, as well as improving access to Child and Young People’s Mental Health Services and NHS assessments. There is also a need for improved early identification of SEND in young children. This could take the form of a thorough screening check during reception year.

- The DfE should develop an understanding of why the attainment of some ethnic groups has been more adversely impacted by the pandemic (for example White and Black Caribbean pupils) than others, including the roles of poverty and pupil absence which are known to vary by ethnicity.