Intro and recap

In the first blog in this series, we examined the relative GCSE English and maths attainment of pupils with additional needs – those with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) and those who speak English as an Additional Language (EAL) and broke our findings down by ethnicity. We drew the following conclusions:

- In 2020, pupils with 6+ years of School Support had similarly low GCSE results to pupils with Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs), who receive greater support for their needs and the protection of a statutory plan.

- This meant that for Gypsy Roma, Traveller Irish, and Black Caribbean pupils with long-term School Support but no EHCP, attainment was in, or near, the bottom quarter nationally.

- This suggests that pupils with 6+ year of School Support may need additional support, particularly during and after the transition to secondary school.

- In 2020, most ethnic groups of pupils who speak EAL and arrived during Years 7-9, and all but one ethnic group among late arrivals in Years 10-11, had attainment below the national median in the core GCSE subjects of English and maths. This demonstrates that late arrival into the school system carries a serious attainment penalty, across ethnic groups.

- Previous research found that some of this low attainment was ‘additional’ or specific to 2020 and the pandemic onset, and extra funding alone would have been unlikely to fix this because it could not turn back the clocks for a group who suffered twofold interruption to their education through migration and then pandemic restrictions.

- The largest attainment gaps for pupils who speak EAL were similar to the largest SEND attainment gaps. For instance, pupils with EHCPs in the Irish, Traveller Irish and Gypsy Roma ethnic groups had attainment gaps of over 30 percentiles below the median; the same ethnic groups, plus Black Caribbean and White and Black Caribbean pupils among those who arrived latest and spoke EAL had gaps of over 30 percentiles. Yet there is almost no policy attention given to EAL.

In this second blog in the series, we will zoom in on pupils with SEND and extend our analysis of 2020 GCSE results to show how attainment differed or was similar for pupils of different ethnicities whose schools made additional provision for SEND, and those whose schools did not offer that provision.

- Previous research by EPI of national data found that two groups experienced increased attainment gaps in 2020, versus 2019, and these were pupils with SEND and pupils who speak EAL.

- Although schools were asked to remain open for in-person teaching for some children with SEND during pandemic lockdowns, some schools struggled to make socially distanced in-person provision for all children with SEND as well as children with social workers and children whose parents were essential workers such as nurses or supermarket staff.

- Our previous research on SEND in primary schools found that there was variation in the probability of being identified with SEND between ethnicities even after accounting for many factors that influence SEND status.

Analysis in Blog 2

The types of provision for SEND we will consider are whether the school had a SEN Resourced Provision, or a SEN Unit; and whether or not the school was among those with the most teaching assistants (in the top quartile for the ratio of teaching assistants to teachers).

The attainment outcome used in this blog series is GCSE English and mathematics grades, expressed as percentile points in the national distribution. Effects of group membership were initially modelled in comparison with the reference group who were White British pupils, with no SEND, who do not speak EAL, and have never been eligible for free school meals since this is the natural comparison group within a regression framework. However, for ease of interpretation given the number of different overlapping group memberships in the analysis, these effects have been translated into comparisons with pupils whose attainment is at the 50th percentile, i.e. those at the median or midpoint of the national attainment distribution. We felt this was an appropriate framing as the school peer group for many pupils includes a variety of ethnic backgrounds, and not just White British pupils.

Longitudinal data on SEND status at the January census each year were used to assign pupils to one of four SEND need categories:

- ‘Never SEND’ pupils had no recorded SEND in any year;

- ‘1-5 years School Support’ pupils never had an EHCP but were recorded with SEND in at least one year and not more than five years by the time they finished year 11;

- ‘6+ years School Support’ pupils never had an EHCP but were recorded with SEND in at least six years by the time they finished year 11;

- ‘EHCP’ pupils had a statutory Education, Health and Care Plan in at least one year by year 11.

In addition to SEND status, our models controlled for deprivation, classifying pupils who were ‘sometimes eligible’ or ‘always eligible’ for free school meals (FSM). Additionally, a control was included for pupils living in medium or high deprivation neighbourhoods (IDACI). This means that the effects we found for SEND and for additional provision do not include variation that is associated with these deprivation indicators.

Additional Provision for SEND and Ethnicity

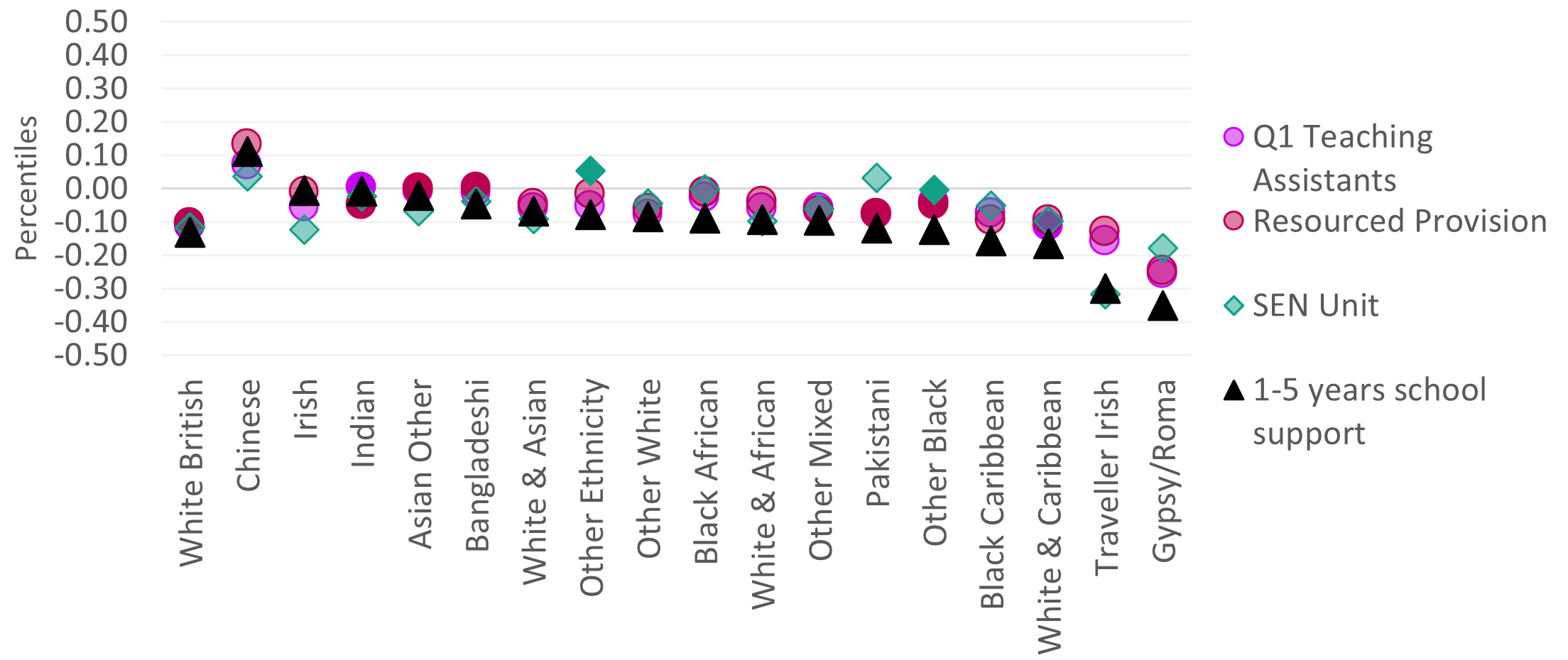

Beginning with pupils with 1-5 years of school support, Figures 1 to 3 below present the attainment effects for pupils with SEND of attending a school with additional provision. The black triangles represent the total group of pupils within each SEND category in each ethnic group. The circles and diamonds represent those pupils within these intersectional groups attending schools with different types of provision that we can distinguish in the data available.

It’s important to note that this is a blunt measure of support available to individual pupils, but it does give us some sense of how broad differences in provision between schools may influence attainment.

However, when interpreting this analysis, we must be alive to the reality that schools whose pupils have the greatest levels of need are those most likely to have more funding available and to receive funding to provide resourced provisions and SEN units, or to employ a greater quotient of teaching assistants. Indeed, pupils with more severe SEND needs may have been admitted to a school precisely because it has a SEN Unit in which they are allocated a place. The differences in provision are therefore not independent of need, even within our SEND categories that aim to group pupils by need level.

It’s also worth reflecting on the fact that the three forms of provision analysed are all to some degree targeted provisions. Some pupils will access resourced provisions or be placed in SEN Units and others will not. Some pupils will be allocated dedicated time with teaching assistant support and others will not. These facets of selection in which pupils receive additional provision may confound the effects of provision.

For example, if there is little or no difference between the attainment of pupils in schools with a SEN Unit and those in other schools, this could be because SEN Units don’t improve attainment, or it could be because SEN Units have successfully closed a gap between pupils with more severe need and those with less severe need. If the attainment of pupils in schools with SEN Units is lower than that of pupils in other schools, this could be because SEN Units have a negative effect on attainment, but it is more plausible that it reflects differences in the severity of need.

So, what can we take from the analysis below? We will focus our discussion on cases where the attainment outcomes are different for pupils of different ethnicities, and we will refrain from drawing spuriously broad conclusions about the effectiveness of one form of provision or another in general.

While we may describe general differences in attainment by form of provision, we will not draw value judgements from these, but rather focus on what the relative position of different ethnic groups is within the broad patterns. In this way we will attempt to avoid making any unjustified conclusions. This cautious interpretation is also warranted because of the exceptional nature of the 2020 GCSE results, and we must not assume that patterns of attainment will be similar in other years. In general, we will treat the following analysis as exploratory.

Attainment of pupils with 1-5 years of school support

Figure 1: Modelled GCSE Attainment of Pupils with 1-5 Years School Support, by Provision

In line with the data limitations just discussed, we do not find evidence of drastically different GCSE attainment for pupils with 1-5 years of school support in schools with additional provision. However, in 2020, there were two groups of pupils that appeared to benefit from attending a school with a SEN Unit, differentially from other ethnic groups. These were:

- Other Ethnicities: +5 GCSE percentiles higher than the median, versus -8 without a SEN Unit

- Other Black: at the median, versus -12 GCSE percentiles from the median without a SEN Unit

In addition, Pakistani pupils with 1-5 years of school support had a marginally non-significant positive effect of attending a school with a SEN Unit, which may have been statistically significant had the group been larger.

In this analysis, because we are making inferences about the relative effects of provision, we will pay more attention to statistical significance than when we were simply describing patterns of attainment between different groups of pupils. This means we will avoid making interpretations when the circles and diamonds are faded out to signify non-significant effects.

It’s worth noting that our modelling gives effects for particular pupils attending particular schools; while it is possible that the correlations between attainment and the presence of additional provision are caused by that provision, it is also possible that these effects represent something else about the pupils or schools concerned that happens to correlate with additional provision but may not be caused by it.

Turning to resourced provision and pupils with 1-5 years of school support, four ethnic groups may have benefited from attending schools with this provision, differentially from other ethnicities:

- Other Black: -5 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -12 without a RP

- Bangladeshi: at the median, versus -5 GCSE percentiles below the median without a RP

- Pakistani: -8 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -12 without a RP

- Other Asian: at the median, versus -2 GCSE percentiles below the median without a RP

Additionally, Black African pupils with 1-5 years of school support had a marginally non-significant positive effect of attending a school with a SEN Unit.

Finally, there were two ethnic groups whose pupils with 1-5 years of school support who may have benefited differentially from attending a school with a high quotient of teaching assistants; these were:

- White & Black Caribbean: -11 GCSE percentiles, versus -17 percentiles without additional TAs

- Indian: at the median, versus -1 GCSE percentile below the median without additional TAs

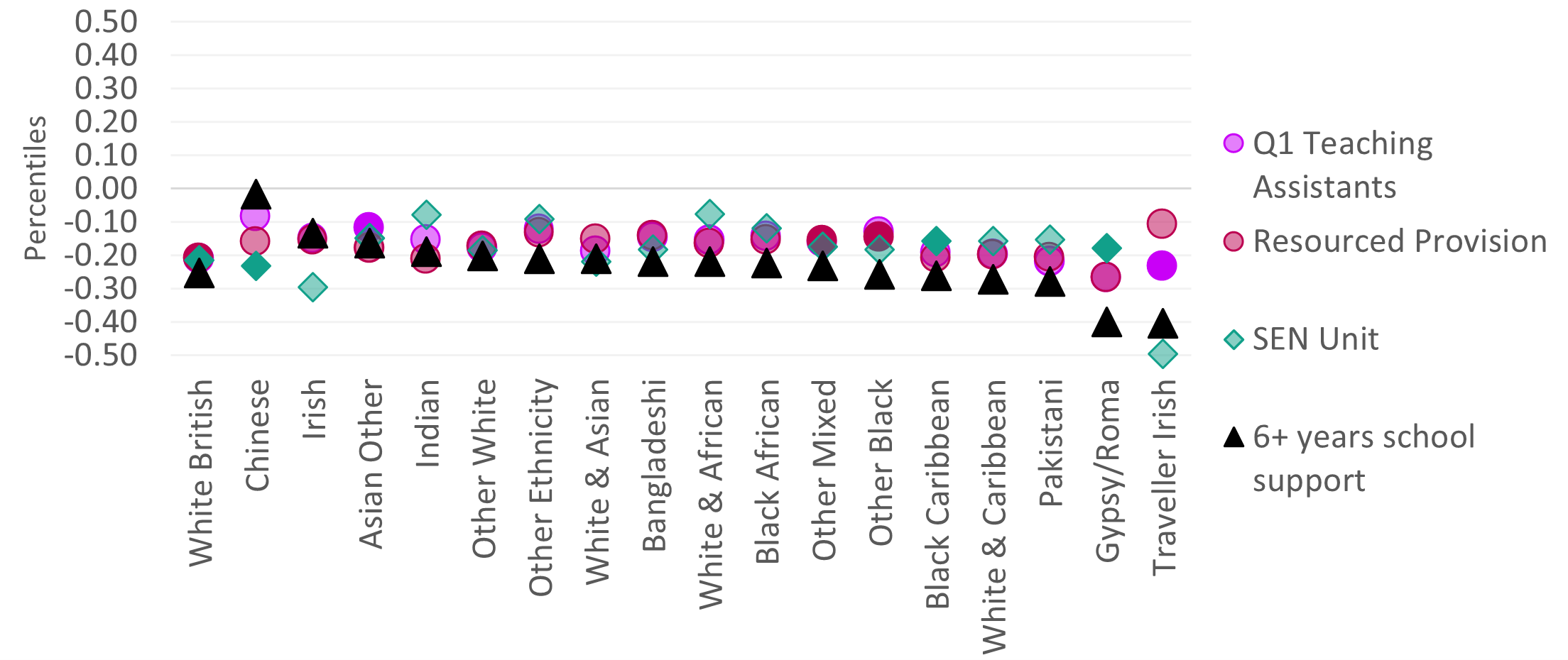

Attainment of pupils with 6+ years of school support

Turning to our category of SEND with medium levels of need, the ‘shadow ECHP’ group that had recorded school support for 6+ years, Figure 4 reports the attainment effects for this group.

Figure 2: GCSE Attainment of Pupils with 6+ Years School Support, by Provision

For this group of pupils with a longer duration of school support, there is a more general pattern of attainment that is higher for pupils in schools with additional provision than those in schools without this provision among ethnic groups with medium and below-average attainment.

Most of these effects remain statistically non-significant, but the small size of the intersections between ethnic groups and this SEND category may be responsible for this in some cases. There are a minority of ethnic groups with provision effects that appear to be negative, but none of these are statistically significant, and small sample sizes may result in atypical attainment profiles.

Despite the small sample sizes, we are able to distinguish a few statistically significant positive effects of attending a school with a SEN Unit for pupils with 6+ years of school support:

- Gypsy Roma: -18 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -40 without a SEN Unit

- Black Caribbean: -16 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -26 without a SEN Unit

- White British: -15 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -21 without a SEN Unit

Indian and Pakistani pupils with 6+ years of school support also had marginally non-significant positive effects of attending a school with a SEN Unit.

Turning to pupils attending schools with a Resourced Provision, three groups of pupils with 6+ years of school support benefited from this provision; these were:

- Other Black: -15 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -26 without a RP

- Other Mixed: -16 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -23 without a RP

- White British: -21 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -25 without a RP

Considering schools with a high quotient of Teaching Assistants, three groups have positive effects of attending these school for pupils with 6+ years of school support:

- Irish Traveller: -23 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -40 without additional TAs

- Other Asian: -12 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -16 without additional TAs

- White British: -21 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -25 without additional TAs

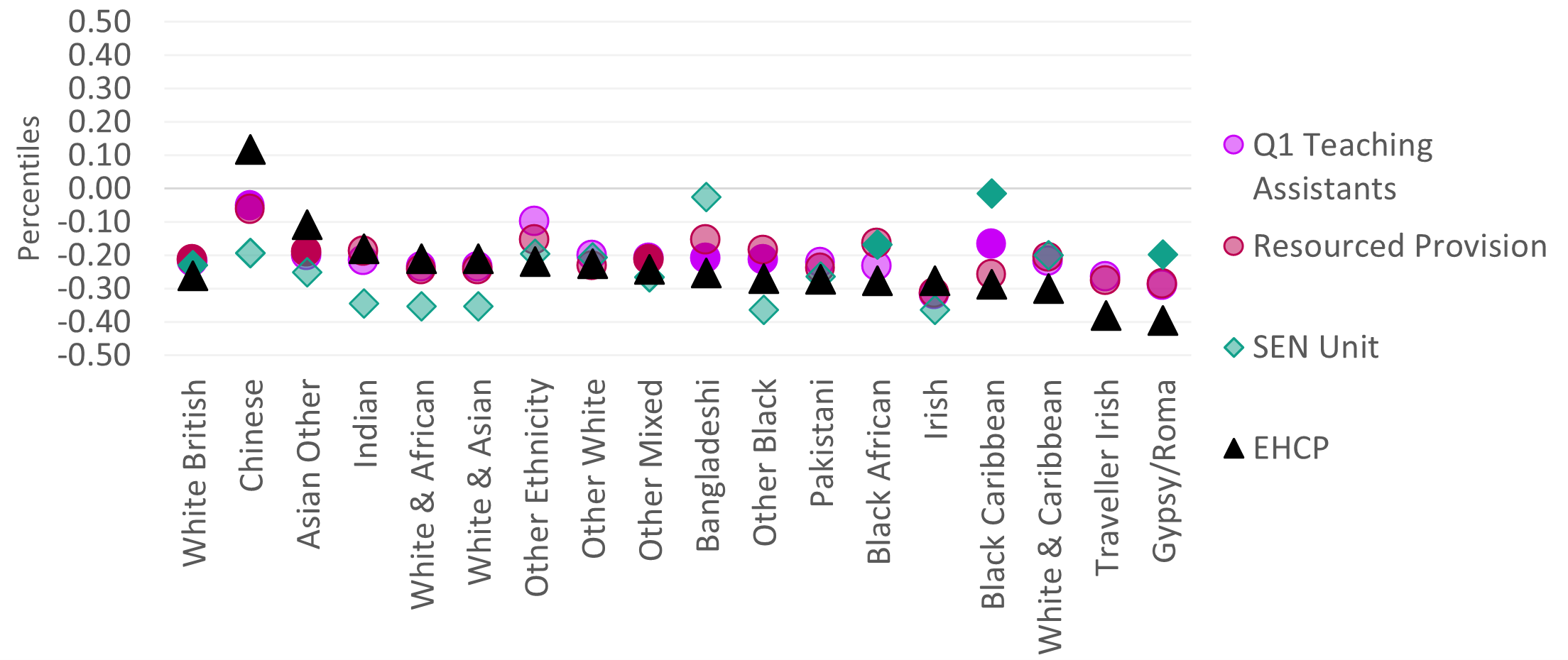

Attainment of pupils with EHCPs

Turning to our highest category of SEND need, pupils with an EHCP, Figure 3 reports the attainment effects for different forms of provision for this group.

Figure 3: GCSE Attainment of Pupils with an EHCP, by Provision

For this group of pupils with the most severe needs as understood by the education system, formalised in a statutory support plan, some larger positive effects of provision were found, particularly for pupils attending schools with a SEN Unit. Again, these were concentrated among the ethnic groups whose attainment of pupils with EHCPs was lowest.

These groups are similar but not identical to the ethnic groups whose overall attainment is lowest; the exception is that Irish pupils had the fifth lowest attainment for pupils with an EHCP in 2020, whereas for all pupils, they had the fifth highest GCSE attainment.

Again, most effects of provision were statistically non-significant for pupils with EHCPs, but a few ethnic groups did have statistically significant provision effects, and these are discussed below. Statistically significant positive attainment effects of attending a school with a SEN Unit, in 2020, were found for four groups with relatively low attainment for pupils with EHCPs, as follows:

- Black Caribbean: -1 GCSE percentile below the median, versus -29 without a SEN Unit

- Gypsy Roma: -20 GCSE percentile below the median, versus -40 without a SEN Unit

- Black African: -17 GCSE percentile below the median, versus -28 without a SEN Unit

- White British: -23 GCSE percentile below the median, versus -26 without a SEN Unit

Turning to pupils with EHCPs attending schools with a Resourced Provision, two much smaller positive effects were found among groups with low and medium attainment for pupils with EHCPs. These were:

- White British: -21 GCSE percentile below the median, versus -26 without a RP

- Other Mixed: -21 GCSE percentile below the median, versus -24 without a RP

One group of pupils with EHCPs had a statistically significant negative Resourced Provision effect, However, it is important to remember that this could reflect the selection of pupils with more severe need profiles into the provision, for this ethnic group. This was:

- Other Asian: -25 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -11 without a RP

Finally, we consider groups of pupils with EHCPs with positive effects of attending a school with a high quotient of Teaching Assistants. There were five groups with statistically significant positive effects, spread across the attainment distribution:

- Chinese: +12 GCSE percentiles above the median, versus -5 below without additional TAs

- Black Caribbean: -17 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -29 without additional TAs

- Other Black: -21 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -27 without additional TAs

- Bangladeshi: -21 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -25 without additional TAs

- White British: -22 GCSE percentiles below the median, versus -26 without additional TAs

Conclusions on the Attainment of Pupils with SEND in 2020

Our analysis found a range of positive effects of attending a school with additional provision. Some of these effects were more concentrated among ethnic groups with low attainment, making them even more valuable from an equity perspective.

Effects of additional provision were largest for pupils with EHCPs (i.e. those with the greatest needs) but were still larger for pupils with 6+ years of School Support than for those with 1-5 years of School Support.

Resourced Provisions were most associated with better attainment of pupils with 1-5 years of School Support, while both SEN Units and Resourced Provisions were equally associated with positive effects for pupils with 6+ years of School Support. For pupils with EHCPs, SEN Units, but mainly higher ratios of teaching assistants, were associated with better attainment.

However, the benefits of additional provision were not evenly spread across ethnicities. They were a patchwork with holes rather than a complete blanket. Some of these holes may be due to small sample sizes not supporting the detection of statistically significant effects. Others are more puzzling.

For example, it’s not clear why Black Caribbean pupils with EHCPs benefited from attending a school with a SEN Unit (+28 GCSE percentiles, net) to a greater extent than Black African pupils (+11 GCSE percentiles). Nor is it clear why Other Asian pupils with 6+ years of School Support benefited from attending a school with a high quotient of teaching assistants (+4 percentiles) but comparable Indian pupils did not appear to benefit.

These comparisons of ethnicities are within the same broad ethnic categories and sit near one another in the distribution of attainment of pupils in the relevant SEND category.

Ultimately, it is not possible to answer every question of interest through data analysis alone. Future research on SEND and ethnicity would benefit from the inclusion of qualitative methods to unpick what is happening on the ground in greater detail. Questions of interest would include the perceptions of pupils, parents and teachers on the pros and cons of specialist provision from the perspective of different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds, and comparisons of male and female pupils. Further questions could address ‘met’ and ‘unmet’ needs, and pupils’ subjective experiences of social inclusion or exclusion in different provision types.

This series of blogs has been produced in partnership with Unbound Philanthropy.

You can read the first in this series here: Ethnicity and additional needs in the pandemic: Intersections between ethnicity and additional needs (1).