Series introduction

In this blog series we will consider the relative GCSE English and maths attainment of pupils with additional needs during the Covid-19 pandemic – those with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) and those who speak English as an Additional Language (EAL) – and in particular, we will make comparisons between pupils with similar additional needs but differing ethnic backgrounds.

Our focus on additional needs is motivated by the increased GCSE attainment gaps experienced by pupils with EAL or SEND in 2020, and our analysis by ethnicity reveals further variation in outcomes within these groups.

In later blogs in this series, we will extend our analysis to show how attainment differed or was similar for pupils of different ethnicities whose schools made additional provision for additional needs, and those whose schools did not offer that provision.

The types of provision for SEND we will consider are whether the school had a SEN Resourced Provision, or a SEN Unit; and whether or not the school was among those with the most teaching assistants (in the top quartile for the ratio of teaching assistants to teachers).

For EAL, we will consider whether the school was in the top quartile with the most teachers of Black and Minority Ethnicity, alongside the teaching assistants measure.

The pandemic context

The context for this analysis was the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic which resulted in the use of GCSE grades based on centre-assessed grades, i.e. grades that were decided by teachers and moderated by school leadership, since examinations were cancelled.

Through this ‘exceptional’ awarding process in 2020, most groups of pupils held their relative positions in the national attainment distribution steady between 2019 and 2020, and indeed guidance issued to schools emphasised the need to ensure that the distribution of grades between more and less educationally advantaged groups of pupils would be fair and justified by the standard of schoolwork completed by each pupil.

Previous research and rationale

Previous analysis by EPI of national data confirmed that this awarding process had worked equitably for economically disadvantaged pupils and between ethnic groups. However, two groups experienced wider attainment gaps in 2020 than in 2019, and these were pupils with SEND and pupils who speak EAL. The rationale for examining the attainment of these groups is twofold.

Firstly, following from our previous research into EAL and attainment and SEND identification, we wished to follow up on ‘hidden’ variation within these groups of pupils.

In the case of EAL, we found that there was substantial variation in attainment outcomes within the EAL group according to the time of a pupil’s first arrival in an English state-funded school (a proxy for earlier or later migration and higher or lower proficiency in the English language), and according to the particular first language spoken.

In the case of SEND we found that there was variation in the probability of being identified with SEND between ethnicities even after accounting for many factors that influence SEND status. It wasn’t possible to determine whether this difference in identification reflected ‘real’ differences in need between ethnicities or differences in recognition of needs and access to support. Both findings suggest that further investigation is warranted into how pupils of ethnic minority heritage are affected by access to support for additional needs.

Secondly, it is important to understand as much as possible about what happened in 2020, who was worst affected, and whether there were any exceptions to this.

It seems plausible that pupils with SEND or EAL needs were ‘left behind’ following the introduction of hybrid remote schooling during lockdowns because they are among the most reliant on one-to-one assistance from teachers in order to make academic progress.

Although schools were asked to remain open for in-person teaching for some children with SEND, they were not asked to do so for children whose first language is not English, and some schools struggled to make socially distanced in-person provision for all children with SEND as well as children with social workers and children whose parents were essential workers such as nurses or supermarket staff.

Definitions of attainment, SEND and EAL

The attainment outcome used in this blog series is GCSE English and mathematics grades, expressed as percentile points in the national distribution. Effects of group membership were initially modelled in comparison with the reference group who were White British pupils, with no SEND, who do not speak EAL, and have never been eligible for free school meals. For ease of interpretation, these effects have been translated into comparisons with pupils whose attainment is at the 50th percentile, i.e. those at the median or midpoint of the national attainment distribution.

Longitudinal data on SEND status at the January census each year were used to assign pupils to one of four SEND need categories:

- ‘Never SEND’ pupils had no recorded SEND in any year;

- ‘1-5 years School Support’ pupils never had an EHCP but were recorded with SEND in at least one year and not more than five years by the time they finished year 11;

- ‘6+ years School Support’ pupils never had an EHCP but were recorded with SEND in at least six years by the time they finished year 11;

- ‘EHCP’ pupils had a statutory Education, Health and Care Plan in at least one year by year 11.

Longitudinal data on EAL status and enrolments at state-funded schools in England were used to assign pupils to one of four categories:

- ‘English First Language’ pupils were never recorded as speaking EAL in any year;

- ‘EAL Arrived by Y7’ pupils were recorded as speaking EAL in at least two years and were found to be enrolled in any state-funded school in England for at least one year between Reception and Year 6, inclusive;

- ‘EAL Arrived Y7-9’ pupils were recorded as speaking EAL in at least two years and were first found to be enrolled in any state-funded school in England between Years 7 and 9, inclusive;

- ‘EAL Arrived Y10-11’ pupils were recorded as speaking EAL in at least one year and were first found to be enrolled in any state-funded school in England in either Year 10 or Year 11.

Ethnicity, gender and attainment

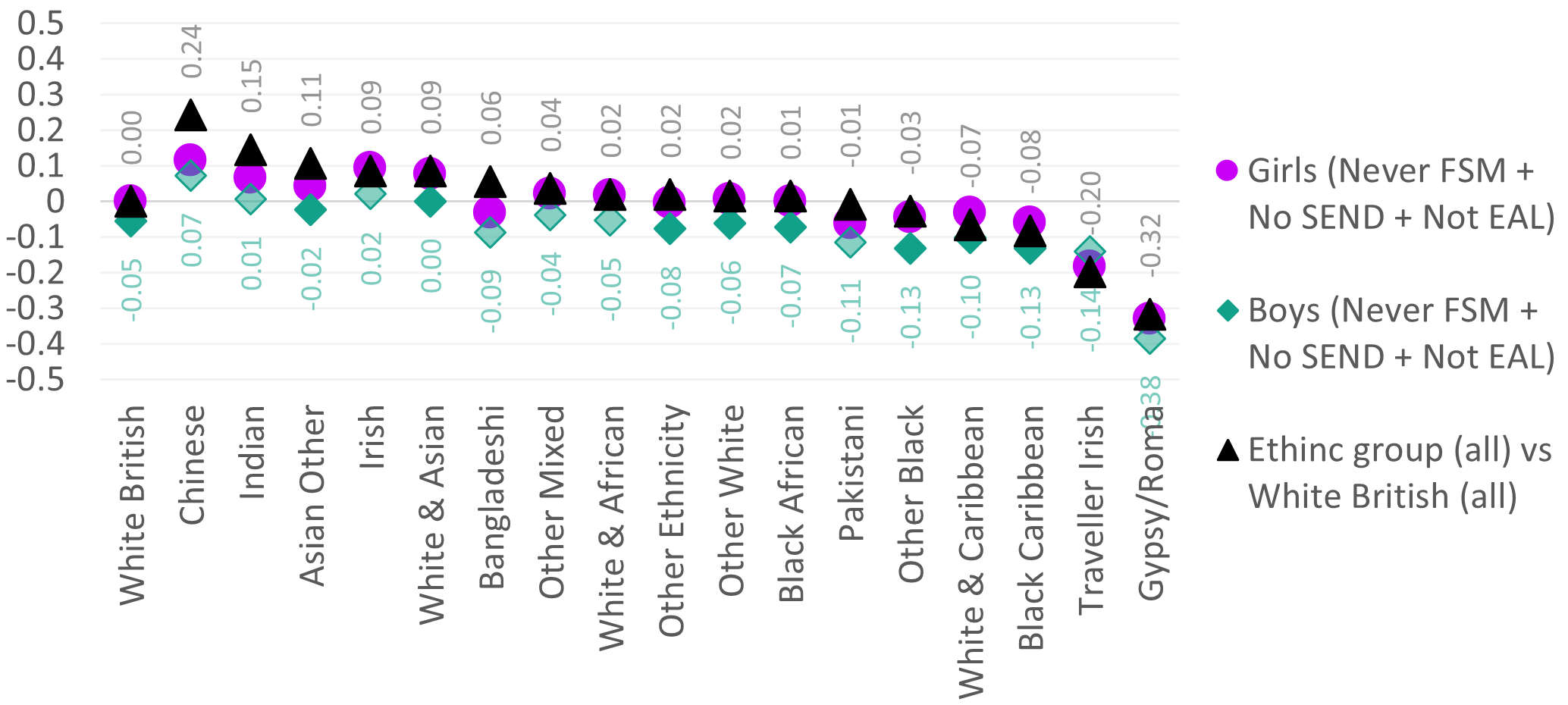

As a starting point for exploring the role of ethnicity, additional needs and additional provision in attainment, we begin by examining pupil attainment by ethnicity. In Figure 1, the black triangles represent the attainment of all pupils in each ethnic group, compared with the median national attainment for all pupils in all ethnic groups, as represented by the horizontal axis value of zero.

The label above each triangle reports the size of the gap in attainment between each ethnic group and the median, expressed in percentiles. For example, Indian pupils have attainment that is 15 percentiles higher than the national median, and Black Caribbean pupils have attainment that is eight percentiles lower than the national median.

Each ethnicity is also represented by a circle and a diamond, representing girls and boys respectively, but specifically those girls and boys in each ethnic group who do not have any additional needs. As girls typically have marginally higher GCSE attainment than boys, the circles for most ethnic groups appear slightly above the diamonds.

Figure 1: GCSE Attainment of All Pupils by Ethnicity, and for Girls or Boys with no Additional Needs

To take an example from Figure 1, Black African girls without any additional needs have GCSE English and maths attainment that is equal to the national median, and for boys without additional needs this is 7 percentiles below the median. The average for all Black African pupils including those with additional needs is one percentile above the national median.

In a few cases, mainly among the higher attaining ethnic groups towards the lefthand side of the figure, attainment of all pupils in the ethnic group was higher than attainment for girls without any additional needs. This seems counter-intuitive at first because pupils with additional needs typically have attainment that is compromised or lowered to some extent by those needs; in other words, their needs are not fully compensated for by provision that schools put in place to support them.

However, this is not always the case when considering minority ethnic groups, and particularly those including many pupils who speak English as an Additional Language. This is because pupils who speak EAL can learn English, given sufficient time and support from teachers and other school staff; and indeed many are already bilingual or multilingual and speak some English by the time they first attend a school in England.

This is especially the case for children born in the UK who have a mother tongue other than English, but who are also exposed to English throughout their lives.

Our previous research on EAL and attainment found that it is simultaneously true that on average, pupils who speak EAL go on to achieve above-average GCSE grades, and that nevertheless a subset of more vulnerable pupils whose proficiency in English is low because they arrived close to Year 11 do suffer a substantial GCSE penalty, since there is little time for this subset of pupils to become proficient in English and learn the curriculum before being assessed for their GCSEs.

What is happening in the case of Chinese, Indian, Other Asian and Bangladeshi pupils is that many within these groups who were proficient in English, or had enough time and support to become proficient, were able to go on and achieve strongly in their GCSEs.

It may be the case that pupils within these groups who speak EAL are supported by parents who value educational opportunity, and/or their parents are highly educated. It is not uncommon to be proficient in English despite this not being one’s first language and it is possible to be eligible for free school meals despite having highly educated parents because qualifications from other countries are not always recognised in the UK in order to access better-paid occupations.

It is also true that some families migrate to England in order to seek educational and economic opportunities and are highly motivated to succeed in school despite any linguistic or economic challenges they face.

Some combination of these circumstances could account for the reversal of the expected pattern of attainment between pupils with and without additional needs for Chinese, Indian. Other Asian and Bangladeshi children.

In Figure 1, there is a spread of attainment across ethnicities including around one third of ethnic groups with above-average attainment, one third with close-to-average attainment, and one third with below-average attainment.

However, around half of ethnic groups have statistically significantly below-average attainment for boys, and several more follow the same pattern but this is not statistically significant, sometimes due to small numbers of pupils in the 2020 GCSE cohort.

The lowest attaining boys in 2020, excluding those with additional needs, were Gypsy Roma boys whose attainment was 38 percentiles below the national median, and six percentiles below all Gypsy Roma pupils. Black Caribbean boys, excluding those with additional needs, were graded 13 percentiles below the national median or five percentiles below the total Black Caribbean group.

At the other end of the attainment distribution, the attainment of Other Asian boys, excluding those with additional needs, was two percentiles below the national median, while comparable girls were 4 percentiles above the national median, and the total Other Asian group including pupils with additional needs had attainment 11 percentiles above the national median.

The intersection of ethnicity and SEND

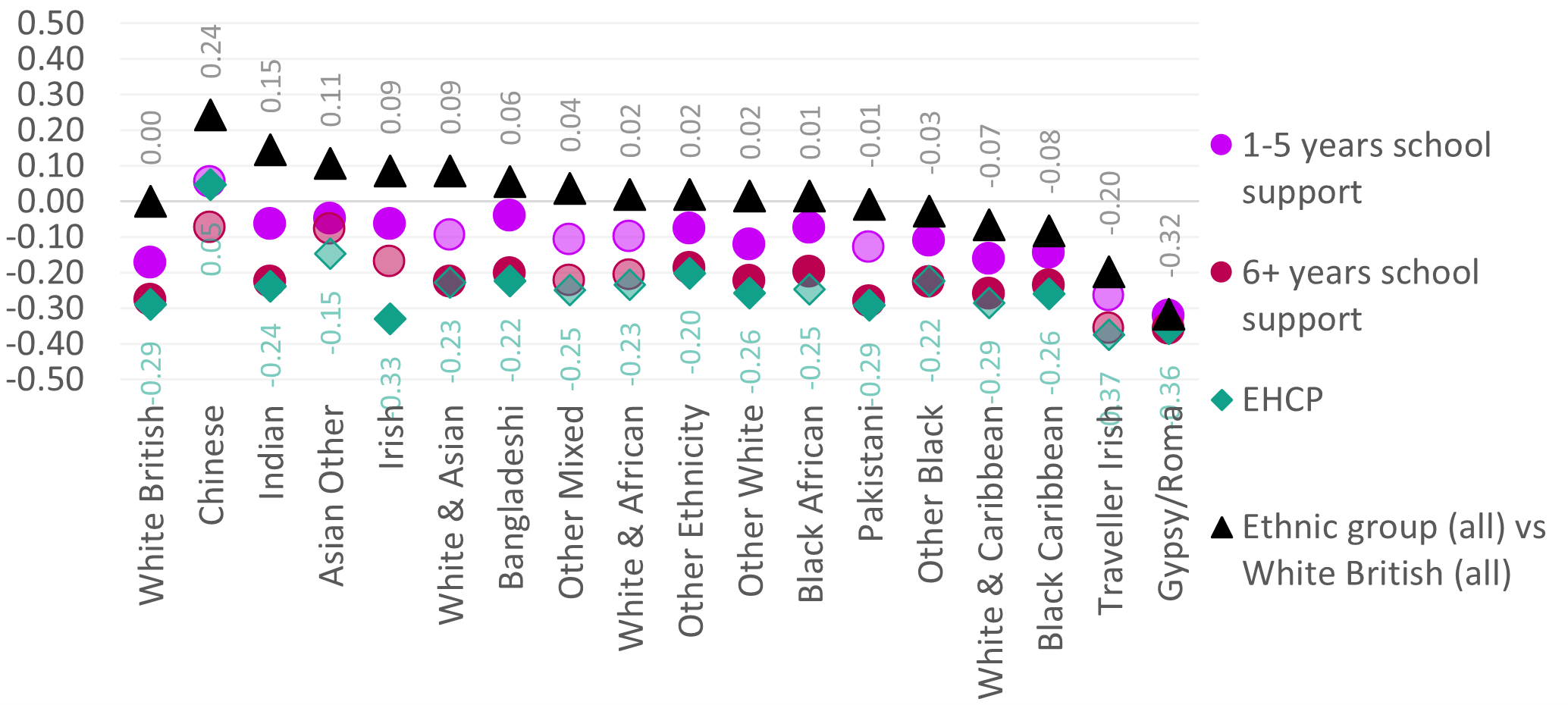

We next consider the effect of membership of the SEND categories in addition to membership of each ethnic group, and how these multiple identities are associated with GCSE attainment. The black triangles in Figure 2 again represent all pupils in each ethnic group, while the circles and diamonds represent those pupils with each category of SEND described earlier.

In general, having SEND and having greater rather than lesser needs, makes more difference to the attainment of ethnic groups with highest overall attainment (on the lefthand side of the chart after White British), than to those with the lowest overall attainment (on the righthand side). This means that pupils without any SEND needs, and without any other additional needs since these are controlled for in the analysis, have attainment that is lower than the national median among the following ethnicities:

- Gypsy Roma

- Irish Traveller

- Black Caribbean

- Mixed White & Black Caribbean

- Other Black

- Pakistani

All other ethnic groups apart from White British have overall attainment that is above the national median, although their pupils with SEND attain below the national median with the exception of Chinese pupils with EHCPs.

Some of the SEND groups in Figure 2 have lighter-shaded circles and diamonds and these represent groups whose attainment gap is not statistically significant. This happens for two reasons; either the group is small and this results in uncertainty about the effect of group membership, or the group’s attainment gap is not sufficiently large given the size of the group, again resulting in uncertainty.

This applies to several ethnicities’ SEND categories. It means that we can’t extrapolate the results reported beyond the pupils in our analysis, i.e. those in the 2020 GCSE cohort in England, but this was already the case due to the exceptional nature of the GCSE results in 2020. As a factual representation of the groups in the analysis, the data points in Figure 2 are still valid even where gaps were not statistically significant.

Figure 2: GCSE Attainment at the Intersections of Ethnicity and SEND Status

We can learn from Figure 2 that pupils with 1-5 years of school support generally had attainment lower than the national median, with the largest gaps among the lower-attaining ethnic groups, in the following cases:

- Gypsy Roma: -32 GCSE percentiles

- Irish Traveller: -27 GCSE percentiles

- White British: -17 GCSE percentiles

- White & Black Caribbean: -16 GCSE percentiles

- Black Caribbean: -14 GCSE percentiles

- Other White: -12 GCSE percentiles

- Other Black: -11 GCSE percentiles

In the case of Gypsy Roma pupils, the attainment of pupils with 1-5 years of school support, and of 6+ years or an EHCP, was not substantially different from the overall ethnic group average.

Turning to pupils with 6+ years of school support, this group’s attainment was generally similar to that of pupils with an EHCP. In this sense, pupils with 6+ years of school support can be thought of as a ‘shadow EHCP’ group whose GCSE attainment is almost as compromised as pupils with EHCPs, albeit after those pupils with EHCPs have received some statutory support for the level of need they experience.

This pattern suggests that there may be a missed opportunity to increase the level of support provided to pupils whose SEND needs continue to be visible in their attainment by the age of 11, as they move into secondary school. In practice many pupils currently lose their school support status on transition to secondary school, and this may be potentially contributing to the pattern of similar gaps for pupils with 6+ years of school support and those with EHCPs.

The largest GCSE attainment penalties for pupils with EHCPs were for the following ethnicities, and were spread across both lower and higher-attaining ethnicities:

- Irish Traveller: -37 GCSE percentiles

- Gypsy Roma: -36 GCSE percentiles

- White Irish: -33 GCSE percentiles

- White British: -29 GCSE percentiles

- Pakistani: -29 GCSE percentiles

- Black Caribbean: -26 GCSE percentiles

- Indian: -24 GCSE percentiles

The intersection of ethnicity and EAL

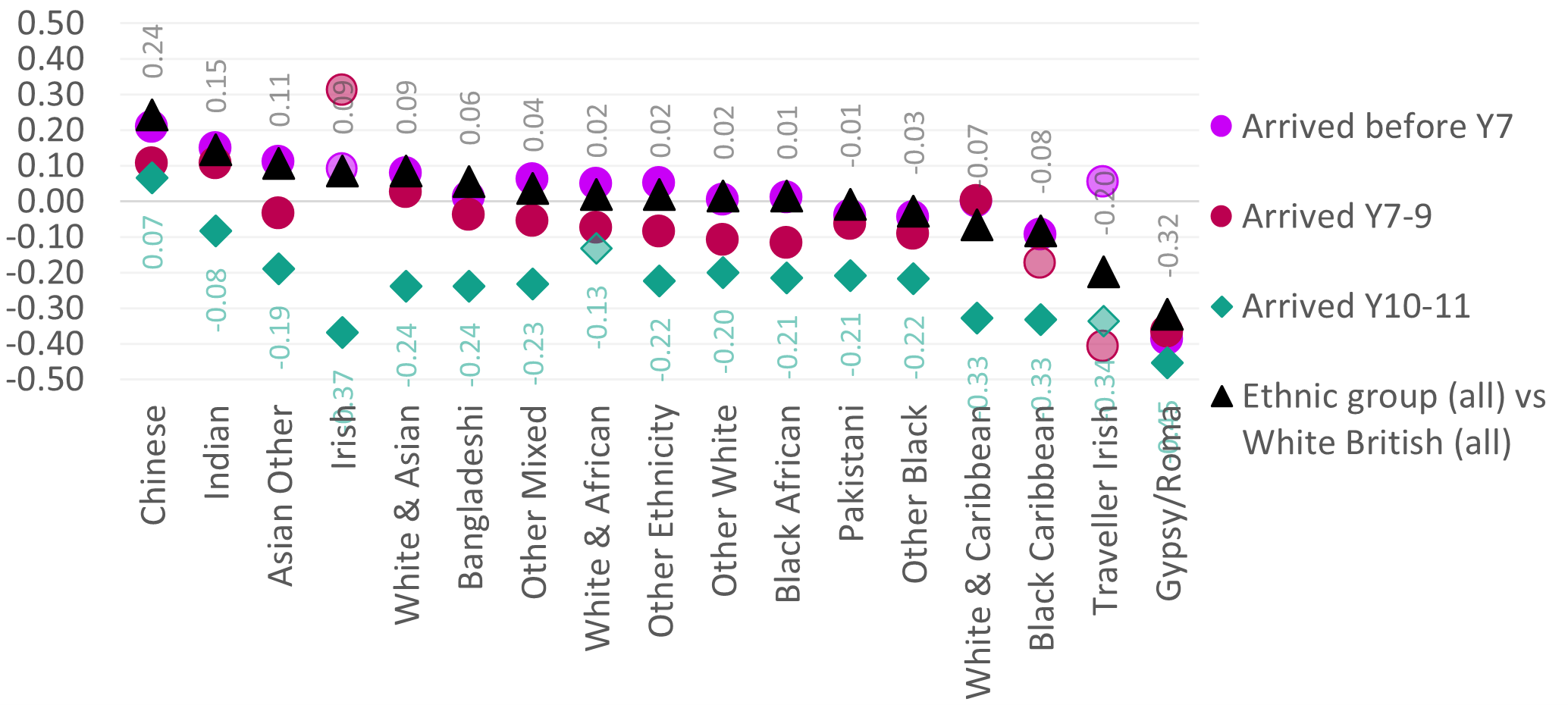

We now shift our focus from pupils with SEND to pupils who speak EAL. As we did with SEND, we consider the effect of membership of the EAL categories in addition to membership of each ethnic group, and how these multiple identities are associated with GCSE attainment.

The black triangles in Figure 3 again represent all pupils in each ethnic group, while the circles and diamonds represent those pupils with each category of EAL.

In general, speaking EAL and having arrived later rather than earlier, makes more difference to the attainment of a cluster ethnic groups with above-average (but not the highest) overall attainment towards the lefthand side of the chart, plus the Black Caribbean and Mixed White & Black Caribbean groups, with low overall attainment.

This pattern is less related to the overall attainment of each ethnic group than we saw with the SEND categories, and it may reflect other factors such as differences in the lives of migrant children before they arrived in England, including their journey here, or in the relative difficulty in learning English when one’s mother tongue is one language versus another.

In general, while the overall attainment of all pupils in each ethnic group is spread above, near to, and below the national median, and the same is true for pupils who speak EAL and had arrived in a state school in England before the start of secondary school in Year 7, pupils who speak EAL and arrived during the course of secondary school most often had attainment below the national median.

This was most extreme for pupils who arrived in Years 10 and 11, who we have previously dubbed ‘late-arriving EAL pupils’. This group had below-average attainment in all but one ethnic group (Chinese) and experienced extreme GCSE attainment gaps in 2020, but this followed a pattern that already existed before the onset of the pandemic.

Figure 3: GCSE Attainment at the Intersections of Ethnicity and EAL Status

As previously mentioned, late-arriving (Year 10-11) EAL groups with the lowest attainment were not confined to ethnic groups with low overall attainment. These included:

- Gypsy Roma: -45 GCSE percentiles

- White Irish: -37 GCSE percentiles

- Irish Traveller: -34 GCSE percentiles

- Black Caribbean and White & Black Caribbean: -33 GCSE percentiles

- Bangladeshi and White & Asian: -24 percentiles

In contrast to the pattern for pupils with SEND, most ethnic groups have above-average attainment for pupils who speak EAL and had arrived before Year 7, including one group with very low overall attainment (Irish Traveller). These groups were resilient to the challenge of learning in a new language by the time they had been in a school in England for at least five years, spanning all of their secondary education:

- Chinese: +21 GCSE percentiles

- Indian: +15 GCSE percentiles

- Other Asian: + 11 GCSE percentiles

- White Irish: +9 GCSE percentiles

- White & Asian: +8 GCSE percentiles

- Other Mixed: +6 GCSE percentiles

- White & African, Other Ethnicity, and Irish Traveller: +5 GCSE percentiles

- Black African, and Bangladeshi: +1 GCSE percentile

A much smaller minority of groups had GCSE attainment above the national median even for pupils who arrived during key stage 3 (Years 7-9), after beginning their secondary education. These were:

- White Irish: +31 GCSE percentiles

- Chinese, and Indian: +11 GCSE percentiles

- White & Asian: +3 GCSE percentiles

Additionally, White & Caribbean pupils who speak EAL and arrived in Years 7-9 had GCSE attainment at the national median.

Conclusions

Our analysis found that, at least in 2020, pupils with 6+ years of School Support experienced GCSE results that were similarly low to those of pupils with EHCPs, who receive greater support for their needs and the protection of a statutory plan.

This was especially problematic for the lowest-attaining ethnic groups: Gypsy Roma, Traveller Irish, and Black Caribbean; whose attainment for pupils with EHCPs was in the bottom quarter of the national distribution.

While the pupils with EHCPs may well have had even lower attainment if they had not received statutory support for their needs, this similarity in outcomes nevertheless raises policy questions:

- What extra support is needed for pupils with longstanding School Support status?

- Is greater needed when pupils transition to secondary school (i.e. greater adoption of measures taken in primary school by the receiving secondary school)?

Our analysis also found that, at least in 2020, most ethnic groups of pupils who speak EAL and arrived during Years 7-9, and all but one ethnic group among late arrivals in Years 10-11, had attainment below the national median in the core GCSE subjects of English and maths.

For the three lowest-attaining ethnic groups, Gypsy Roma, Traveller Irish and Black Caribbean, and also for White & Caribbean pupils, arrival in Years 10-11 resulted in attainment in the bottom quarter of the national distribution.

We know from previous research that some portion of this low attainment was ‘additional’ or specific to 2020 and the pandemic onset that saw schools adopt remote learning for most pupils, and the submission of centre assessed GCSE grades to awarding bodies based on the written work that pupils had undertaken, rather than on examinations.

Funding alone would have been unlikely to fix this problem because it could not turn back the clocks for a group who did not experience the ‘normal’ path to GCSEs, twice over, by having an education interrupted by migration, and by having their GCSEs interrupted by a global pandemic.

A final point to note is that the largest attainment gaps for pupils who speak EAL were of similar size to the largest SEND attainment gaps. Yet there is a vast discrepancy in the amount of policy attention towards SEND and EAL.

While there are many long-standing problems in SEND policy, there at least is a SEND policy. Aside from a modest amount of additional school funding, there is no policy for how schools ought to support children who speak English as an additional language.