Education technology (edtech) has been available for the past couple of decades, but since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the move to online learning during subsequent lockdowns, the use of edtech in schools has accelerated. With substantial government investment now directed towards edtech, it is important to determine whether teachers are using these tools effectively and benefiting from them.

In this blogpost, we examine the current landscape of edtech usage in schools, its impact on teacher workload, and government efforts to support equitable and effective edtech adoption. The blog draws on findings from previous EPI convening of school leaders, academics and civil servants alongside DfE and Teacher Tapp data.

How many teachers are using technology?

Despite the Department for Education investing over £4 million in AI tools for schools earlier this year, the use of technology in schools is poorly understood at a national level. The most basic requirement for teachers to access technology, such as AI tools, is that they have a device provided by the school to securely use them on. The DfE’s 2022-23 Technology in Schools Survey shows that while most teachers have access to hardware, a small but concerning proportion still do not: 1 per cent of primary school and 2 per cent of secondary school IT leads reported that laptops were unavailable for their teachers. It is also not clear whether teachers that do have devices are allowed to take them home, to plan lessons for example. The data highlights a significant discrepancy: in the DfE survey, 6 per cent of IT leads said that teachers were not allowed to take devices home, but in a Teacher Tapp survey, a quarter reported that they are not provided with a device that they can use outside of school.

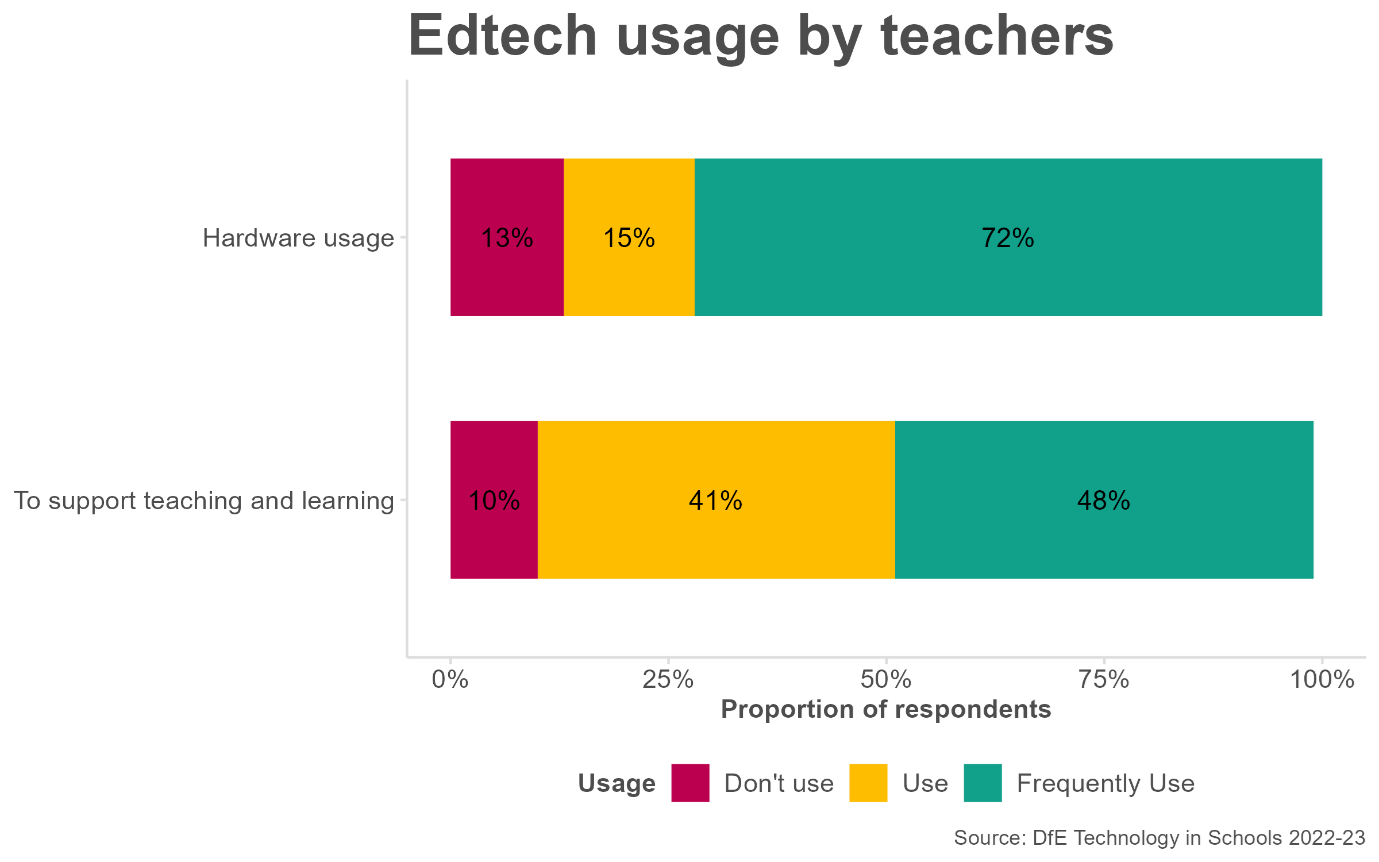

Inequalities are also evident in how frequently technology is used in classrooms. In the DfE survey, most teachers (87 per cent) reported using some form of hardware such as laptops or interactive whiteboards to some extent during their lessons, while a smaller percentage (72 per cent) said they used this hardware frequently. While 90 per cent of the surveyed teachers reported they have used technology in the last 12 months to support teaching and learning techniques, only 48 per cent reported that they use edtech frequently for these purposes. This points to a disparity in the consistent integration of technology into teaching practices, which may limit the potential benefits of edtech for both teachers and students.

There is no clear explanation for why some teachers use technology frequently and benefit from it while others do not. According to the DfE data, the most valued sources of information for teachers are recommendations from other teaching staff, both within and outside their school (40 per cent), and insights from other schools that use technology well or from user reviews (39 per cent). Findings from our convening suggest that drivers may also differ by level of seniority: it was reported that headteachers looked to available research and guidance for advice while subject leads relied more on peer reviews.

More research is necessary to understand the extent to which edtech is being used and the factors influencing its adoption, particularly given that the government has invested in technology to reduce teacher workload.

Existing policy guidance is relatively light. An education technology strategy was published in 2019 and then, in 2023, a review into EdTech Quality Frameworks and Standards. The review finds that there is no single framework or standard in England that facilitates the evidenced-based judgement of what constitutes a high quality, effective edtech product. Many convening participants called for government intervention in this area. They said that, without a policy that sets out minimum standards for devices and products, it is very challenging for schools to decide which edtech to invest in and to know that it is safe and high-quality for their pupils. The government has committed to publishing a safety framework on AI products for education later this year; it would be worthwhile to consider producing a similar framework for all edtech products.

Can edtech help teachers reduce their workload?

Edtech may present opportunities to address teacher workload in England and indeed forms a central part of government plans to reduce it, and tackle the recruitment and retention crisis. Teacher workload is often cited as a factor that affects teacher wellbeing and retention, especially

due to the time-consuming nature of non-teaching tasks. OECD data from 2018 found that time spent on marking, lesson planning and administrative work was associated with work related stress, and a quarter of teachers’ time was spent on these activities.

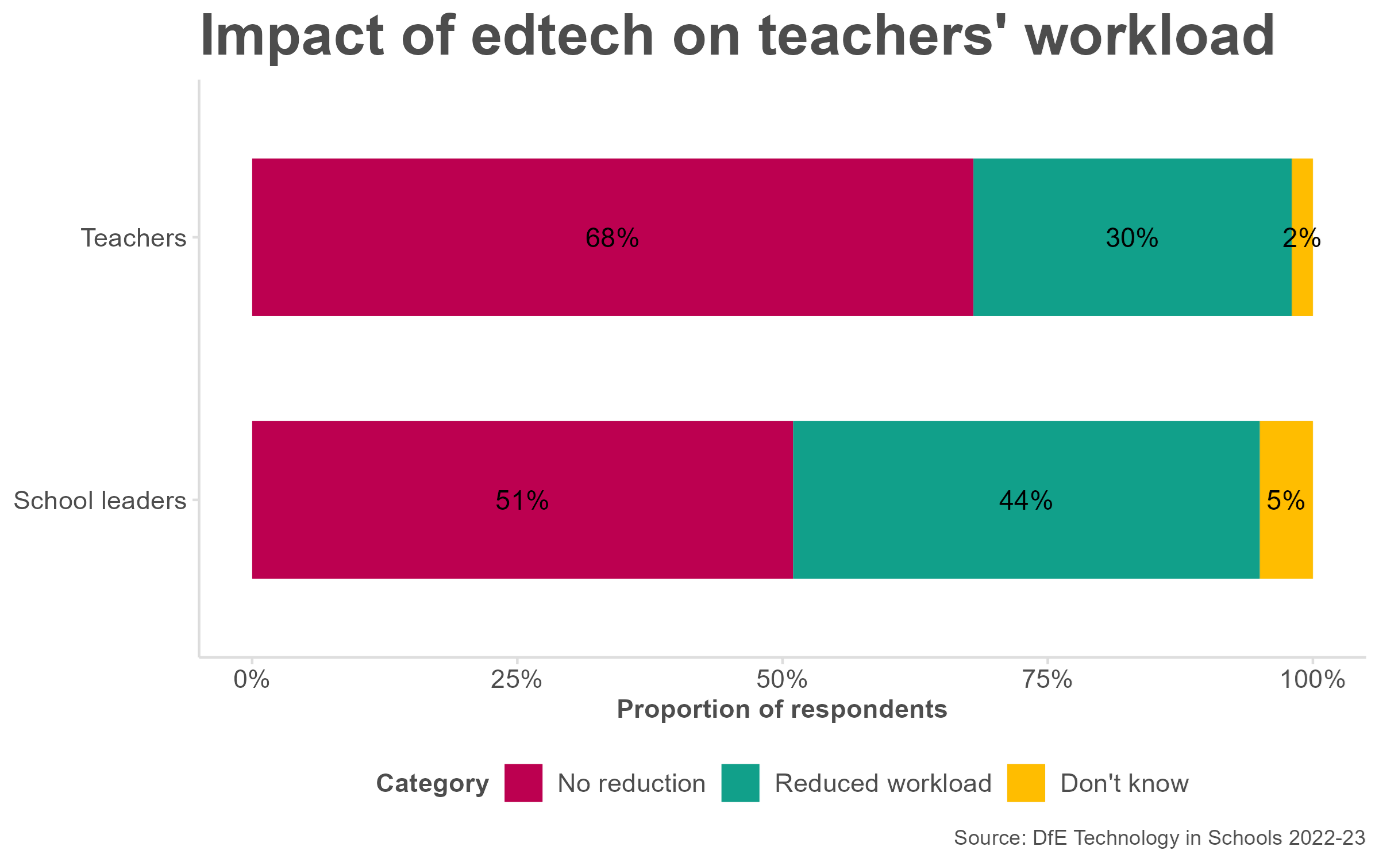

Despite the potential benefits of edtech, its impact has not been felt equally among educators. During our convening, participants suggested edtech presents a key opportunity to personalise learning according to the needs of different pupils, a practice which can otherwise take considerable time and resource. Yet DfE data reveals that the reality in schools is far from this ideal. Although we know that most teachers have access to hardware, there are significant inequalities in how technology is reported to reduce workload. In 2022/2023, only 30 per cent of teachers and 44 per cent of school leaders reported that technology had reduced their workload since 2019/2020.

Moreover, while some teachers acknowledged the value of technology for specific administrative tasks, most did not find it helpful more widely. Specifically, 32 per cent of teachers felt that technology supported them extremely well in tracking pupil progress, 40 per cent in planning lessons or curriculum content, and 42 per cent in collaborating and sharing resources. These figures indicate that for a substantial number of teachers, edtech is not helpful in assisting them with some stress-inducing tasks.

Further research is needed to understand the reasons behind the relatively small and unequal impact of technology on teacher workload, particularly given the government are investing in edtech to reduce it. Participants in our convening highlighted that teacher training is critical for effective usage and recommended that use of specific edtech products as well as wider digital skills should be part of the CPD offer for every teacher. This is backed up by DfE survey data, which found that teachers who received edtech training were more likely to report that technology effectively supported their classroom activities.

Access and equity

Questions remain about which schools have lower levels of effective edtech adoption. It is possible that schools with greater resources and openness to technological integration use more edtech and potentially derive more benefit. If this is the case, there is a risk that greater investment in edtech by government will increase inequalities in access and benefits. Unfortunately, no data currently maps edtech usage against socioeconomic indicators, leaving a critical evidence gap.

In our convening, participants spoke repeatedly of the challenge of the digital divide, highlighting disparities in connectivity that some schools must overcome, before even trying to tackle barriers such as hardware access and selecting the best products for their schools. Teacher Tapp reported that nearly half of the teachers they surveyed in 2024 do not have reliable wi-fi across schools. The recent budget announced an additional £500 million to improve broadband and mobile coverage across the country, and it was announced in 2022 that every school in England would have access to high-speed internet by 2025. With the change in government, it remains to be seen if they are still trying to meet this target.

Conclusion

While technology is accessible to most teachers, not all of them seem to derive the same benefits from it. To maximize the benefits of edtech in education and ensure equitable access, several criticalchallenges must be addressed including current disparities in connectivity, gaps in teacher training and CPD, and a lack of current guidance on what high-quality edtech products look like.

To address these challenges and inform policy, more research is needed on the actual usage and adoption of edtech products in schools in England, especially in schools with more disadvantaged pupils, and on whether edtech is really the silver bullet it purports to be in reducing teacher workload.