What is the reaccreditation process?

In January 2021 the Department for Education (DfE) announced a review of the initial teacher training (ITT) market. The review was conducted by a group of five independent experts and considered what reforms might be required to ensure that all trainees received high-quality training.

The group reported back in July 2021 and, among other things, recommended that all ITT providers be required to re-accredit their provision against new standards. The government accepted most of the recommendations and announced that all training providers hoping to deliver courses leading to qualified teacher status (QTS) in 2024-25 would need to apply for accreditation against new guidance.

There have been two rounds of applications in 2022. Several notable providers were denied accreditation in the first round and forced to reapply in the second round. The results of the second round were published on 29 September and, again, several high-profile providers were denied accreditation. The results of appeals against the decisions of the first and second rounds are expected to be published in the coming weeks and this page will be updated when they are.

The loss of accreditation means that some providers will no longer be able to deliver courses from September 2024. This may affect the number of trainees who are able to access ITT and, in turn, the number of teachers who enter the profession.

EPI analysis

In this policy analysis we assess the scale of the challenge facing the government. We consider the number of trainees who trained in 2022/23 at providers who are not presently accredited for ITT training in 2024/25. This shows how many providers and places may be lost from the market over the next two years because of the reaccreditation process.

There are limitations to this approach:

- We do not know if all providers in 2022/23 applied for accreditation, only whether they have received it. They may have dropped out of the ITT market regardless of the outcome.

- We do not know the capacity of accredited providers who did not deliver ITT in 2022/23.

- Data from accreditation and provision in 2022/23 is matched on the name of the provider and some providers may have merged or changed their name for the application.

- We do not know the response of existing providers to changes in the market. They may increase their capacity or merge with unaccredited providers to provide more places.

Despite these limitations, examining the characteristics of providers who are not accredited for 2024/25 is a useful starting point for understanding the scale of the challenge facing teacher recruitment.

The national impact of the reaccreditation process

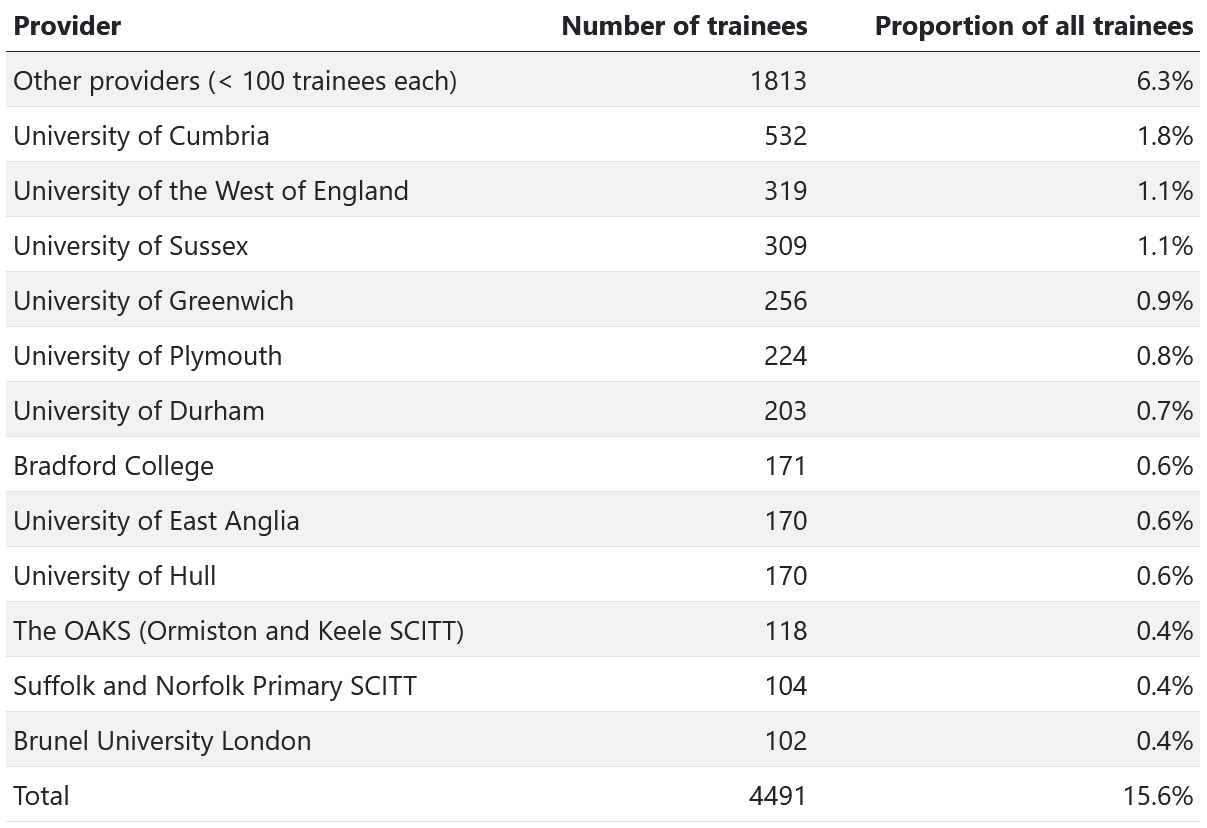

In 2022/23 there are 28,797 trainees on ITT courses at 226 providers.1 The DfE has confirmed accreditation for 179 providers in 2024/25, 21 of which did not provide ITT last year. That means 68 of last year’s providers have lost, or given up, their accreditation (see Figure 1). In aggregate, those providers trained 4,491 people, which is 16% of all trainees in 202223.

That does not necessarily mean that there is less capacity in ITT provision for 2024/25. New providers have been accredited and may take on the trainees who would otherwise have been taught by the providers that lost their accreditation. If the accreditation process has successfully selected the institutions providing better training, then it may be that the quality of provision rises as a consequence of these changes. However, there is a risk that the loss of expertise and capacity in some areas will lead to a reduction in the number of trainees who are able to gain a place in ITT at a time when many subjects are already struggling to recruit suitably qualified trainees.

Figure 1: Number of 2022/23 trainees at providers who did not gain accreditation

The impact on STEM subjects

Recruitment to ITT has been particularly difficult in some STEM subjects over recent years (Figure 2). Physics has struggled to attract trainees and has recruited fewer than half the target number for several years. The loss of accreditation for some providers that specialise in physics could exacerbate the situation if those places are not available at other providers.

Figure 2: Proportion of recruitment target achieved in each subject

Postgraduate ITT recruitment as a percentage of each year’s target. Each line represents a subject, STEM subjects are highlighted in green.

(Source: Department for Education Initial Teacher Training Census 2022/2023)

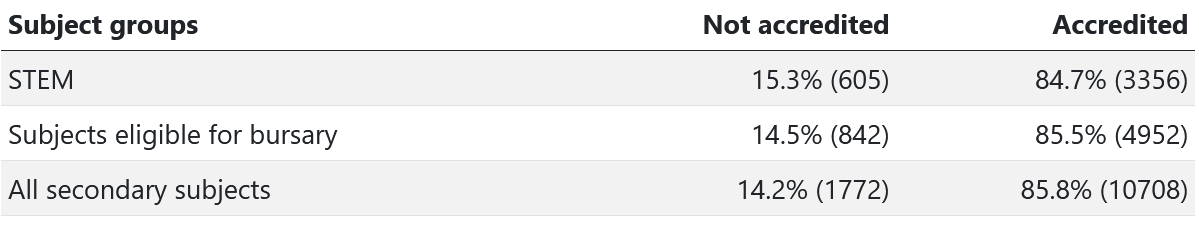

Figure 3 shows the proportion (and number) of trainees in each subject group who trained in 2022/23 at accredited and unaccredited providers. The providers who have lost their accreditation trained a total of 605 STEM teachers in 2022/23, of which 77 were physics teachers. That totals 19 per cent of all physics teachers trained that year. They also trained a similar proportion of the trainees in subjects eligible for bursary payments, which are those typically considered shortage subjects.

Figure 3: ITT recruitment in 2022/23 by subject group

We cannot know what subjects the new providers will specialise in, nor how much existing providers in STEM subjects will expand their recruitment, so it is unclear how much extra capacity is required by 2024/25 to compensate for the loss of accredited providers. DfE is working to encourage partnership between successful applicants and those that missed out. The experience and relationships held by existing providers are not easily replicated so it is important for DfE to be actively considering the level of capacity, at both national and regional levels, for 2024/25.

The regional impact

The impact of the rejected providers’ withdrawal from the market will not affect all regions equally. A glance at Figure 1 shows that some large university providers have not gained accreditation, which is likely to disproportionately affect the regions in which they are based. Half of ITT graduates move less than 25km from their training location to their first job and 94 per cent move less than 200km, so high-quality local provision is essential for schools in the region.

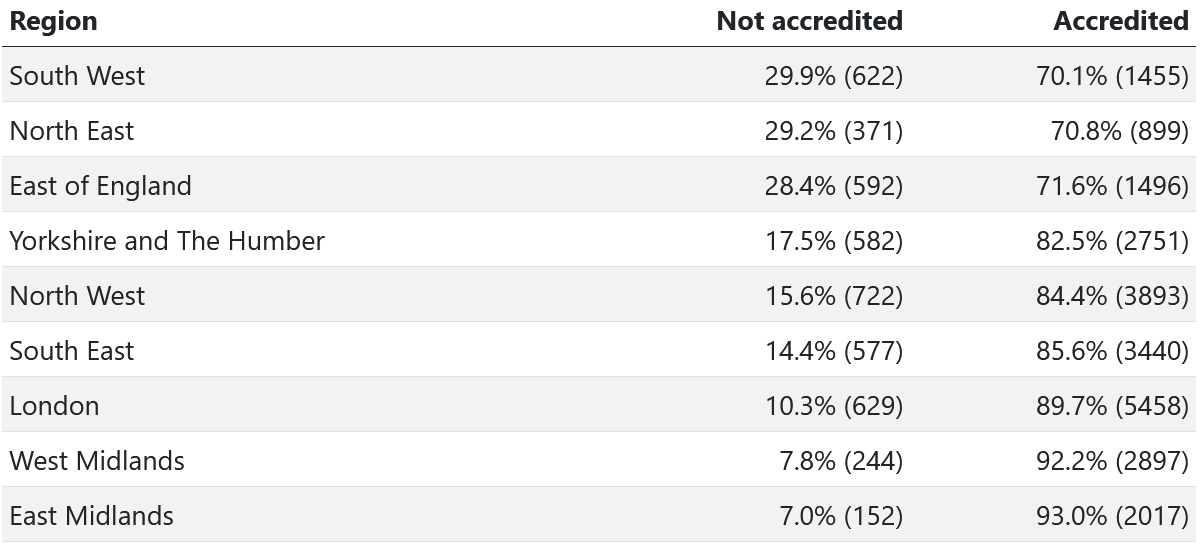

Figure 4 below displays the proportion and number of trainees whose 2022/23 providers did not gain accreditation in each region. It shows that these providers trained nearly 30 per cent of all trainees in the South West, North East, and East of England.

Figure 4: ITT recruitment in 2022/23 by region and 2024/25 accreditation status

Mapping that data emphasises the disparity of the impact across regions. The pattern is similar for STEM provision, with the North East losing up to 31 per cent of the STEM places they have in 2022/23 and the East of England losing nearly a quarter. This is a particular concern in the North East, which suffered comparatively heavy learning losses during the pandemic and sees lower outcomes at GCSE than other regions. A substantial loss of ITT places may exacerbate existing problems.

It is possible that places will be provided in these regions by newly-accredited institutions and this is something DfE should be actively working on. If the existing provision were of low quality then improving it is essential if the local schools are to improve. However, putting so many places at risk in a single year requires careful management and planning. Removing poor provision with no substitute is unlikely to help local schools that already struggle to recruit in shortage subjects.

Figure 5: Proportion of trainees in each region at providers that did not gain accreditation

(Source: EPI calculations using Department for Education Initial Teacher Training Census 2022/2023)

Differences by type of provider

Although it is tempting to focus on the high-profile universities that did not gain accreditation, examining the accreditation rates by route shows that universities fared comparatively well (Figure 6). Of the 138 SCITTs that provided ITT in 2022/23, fewer than two-thirds gained accreditation for 2024/25 in these two application rounds. By contrast, over 80 per cent of universities gained accreditation.

Figure 6: Proportion of 2022/23 providers that did not gain accreditation by route

(Source: EPI calculations using Department for Education Initial Teacher Training Census 2022/2023)

Conclusion

DfE’s market review is likely to have a marked effect on the ITT market through the reallocation of about 16 per cent of places away from providers who will no longer be accredited to train teachers. The impact of this reallocation will be felt most acutely in the regions where the rejected providers are based, notably in the East of England and the North East. Trainees do not often move far from their home region to teach so the risks to provision are greatest in these regions.

Rejected providers do not account for an unusually high proportion of trainees in shortage subjects overall but the training of physics, maths, and computing teachers is likely to be as affected by these reforms as training in other subjects.

It is possible that the long-term impact of the re-accreditation process will be positive if it serves to increase the quality of provision. In the meantime, DfE will need to ensure that there is no shortage of places or decline in provision in shortage subjects and regions that have lost the greatest quantity of places.

This policy analysis has been supported by the Gatsby Foundation. Gatsby is a foundation set up by David Sainsbury to realise his charitable objectives. It focuses support on a limited number of areas: plant science research; neuroscience research; science and engineering education; economic development in Africa; public policy research and advice; the Arts.

Footnotes:

- Numbers in this analysis are calculated from DfE’s published provider-level tables. They do not exactly match the published headline figures in all cases but are consistent within the analysis. For example, the total number of trainees calculated from the provider tables (28,797) differs by 0.6 per cent from the headline figure (28,991).