Statistics released today by the Department for Education show that teachers continue to leave the profession at a growing rate, and there are now fewer teachers in the profession than in the previous year. At the same time class sizes have risen, putting further pressure on schools that are already struggling to cope with squeezed budgets.

Since taking office at the beginning of 2018 the Secretary of State for Education, Damian Hinds, has made the wellbeing of teachers a priority for his Department. In speeches to two headteacher unions he emphasised that his “…top priority is to make sure [teaching] does remain an attractive and fulfilling profession” and noted that “that employment and retention are difficult for schools– and it is not getting easier.”

The school workforce statistics released today by his department highlight the extent of the problem.

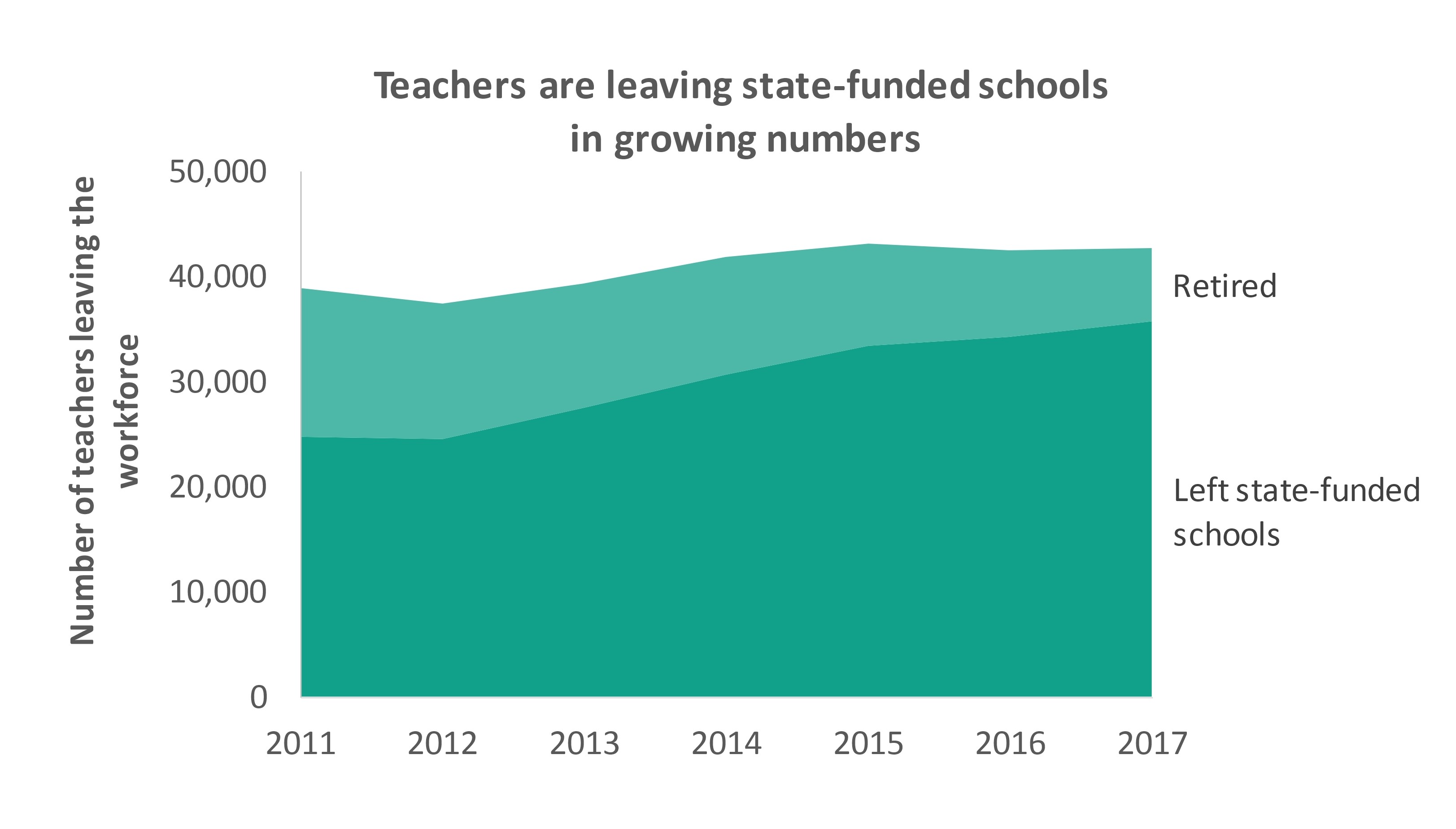

The Department’s headline figures show that the rate at which teachers are leaving has stabilised over the past three years, with one in ten qualified teachers leaving each year. However, that story conceals the reasons for their departure and, underneath the headline, there are a growing number of teachers choosing to leave state-funded schools to pursue a career elsewhere.

The teaching workforce is becoming younger and less experienced each year and, as the number of experienced teachers declines, so too does the number of teachers who are retiring. The chart below shows that the balance is accounted for by those who are leaving the state-funded system in growing numbers

It is tempting to think that these figures represent people who have become disillusioned with teaching but the NFER’s research suggests that is not the case. They found that half of the teachers who left the profession without retiring moved to teaching posts at independent schools. The problem is not that teaching is unattractive but that teaching in state-funded schools is no longer as rewarding as it once was.

The Department is alive to these problems and, in 2014, launched a ‘workload challenge’ to help reduce the long hours worked by teachers. It is unclear how much of an effect that has had on teachers’ hours, but these latest statistics suggest it has done little to encourage teachers to remain in the state-funded sector.

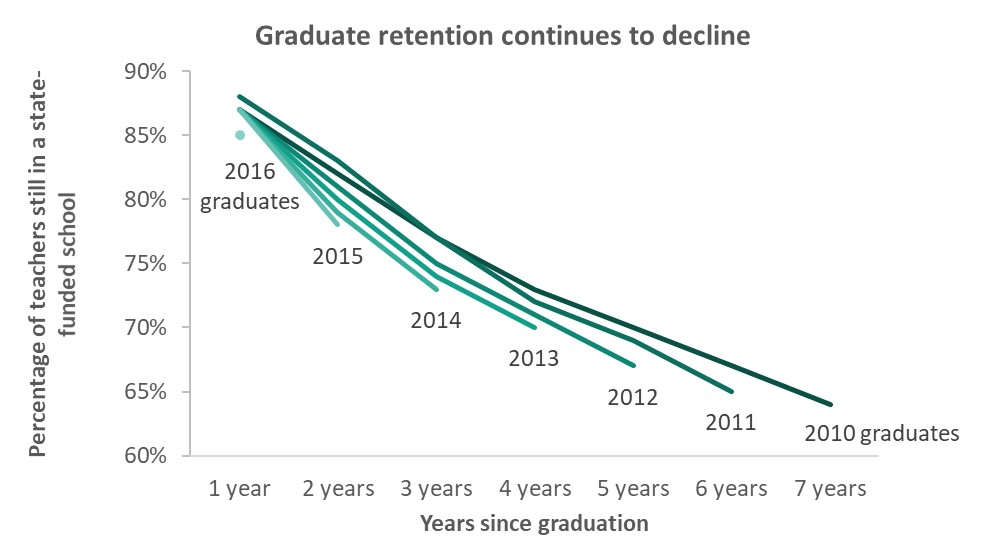

Even among new graduates to the profession, who have joined since the workload challenge began, dropout rates are increasing and each year’s graduates are more likely to leave the profession than the previous year’s. 87 per cent of 2010 graduates were still in the profession after 1 year, compared to only 85 per cent of 2016 graduates, which is a difference of 200 teachers.

These departures and the consistent failure to meet recruitment targets means that there were over 5,000 fewer teachers in UK schools in 2017 than there were in 2016. The immediate consequence is that class sizes have risen and they are likely to continue to rise unless there is either an increase in funding or a reduction in teachers’ administrative workload.

There is also a population bulge that has worked its way through primary schools over the past few years and is about to hit secondary schools, increasing their pupil numbers by nearly 20 per cent over the coming decade. So far, the government has not clarified how it expects schools to cope with the increased pressure.

One route to increasing recruitment and retention of teachers may be through a bump to their pay, which has risen far slower than inflation since 2010. The School Teachers’ Review Body is expected to publish its recommendations to the Government shortly and could recommend a hike to reduce the gap.

However, that will pose further questions for the Government, which has already committed to keeping school funding per pupil flat in real terms for the next two years.

Without additional funding, schools will struggle to accommodate any pay increase. Research released earlier this year by EPI found that up to 40 per cent of state-funded schools in England are unlikely to receive enough government funding in 2018-19 to afford even a 1 per cent pay rise for their staff. For 2019-20, that proportion rises to nearly half of schools. Budget pressures are particularly challenging for the secondary schools who will feel the rise in pupil numbers most keenly: in 2016-17, over a quarter of all local-authority secondary schools were already in deficit.

The Secretary of State has homed in on the right issue with his concern about the attractiveness of the teaching profession – but the latest figures show the challenge facing him may be far greater than he anticipated.