Summary

- Social and emotional learning (SEL) is concerned with fostering children’s social and emotional skills within educational settings, alongside their academic skills. This can include developing young people’s relationships, communication, decision-making, self-esteem and behaviour.

- SEL can play a central role in helping children to develop the skills for educational success and lifelong wellbeing.

- As well as supporting pupil re-engagement after school closures, SEL can contribute to reducing the long-standing attainment gap between disadvantaged children and their peers.

- Despite this, there is no targeting of social, emotional or mental health in the government’s education recovery plans or as part of the levelling up agenda.

Given the evidence, the government should pursue the following policies:

- Integrate SEL into the curriculum rather than delivering it in fragmented, one-off sessions.

- Provide high-quality teacher training and ongoing support to ensure staff feel confident teaching the SEL curriculum and adapt it for diverse groups of pupils. Schools should take into account the wellbeing of staff as they are more likely to be able to support pupils if their own needs and competencies are addressed.

- Encourage the adoption of a whole school approach to SEL, in which students have opportunities to apply skills in different situations and observe them being practiced by adults and peers.

- As part of this, encourage the involvement of students and parents in planning, implementing, and evaluating approaches to SEL. This would also ensure that the needs of diverse groups are considered.

- Ensure that targeted interventions to support children at particular risk of poor outcomes are accessible.

The government must also consider that:

- Current pressures on schools to achieve higher attainment standards are likely to stand in the way of evidence-based approaches to SEL

- Ofsted’s new ‘personal development’ inspection category may help to change this, but, without adequate support for schools in place, could lead to the introduction of superficial and fragmented interventions.

Social and emotional learning: An evidence review and synthesis of key issues

Mental and behavioural disorders account for one of the largest and fastest growing categories of the burden of disease worldwide.[i] The loss, anxiety, and frustration experienced by many as a result of the pandemic is only likely to exacerbate this trend further.[ii] For children and young people, school closures led not only to learning loss but also meant missing out on in-person interactions and support from peers, teachers, and other education professionals.

In response, the UK Government announced various streams of funding to support mental health in England, including £79m to expand children and young people’s community health services and the provision of mental health support teams in schools. Yet research shows that the prevalence of mental illness rose substantially from one in nine to one in six children during the pandemic.[iii] Considering that child and adolescent mental health services were serving less than half of children with a mental illness before the pandemic, more needs to be done.[iv] In a recent NAHT survey, 63 per cent of school leaders stated that addressing the emotional and social burdens of the pandemic is a priority and Nadim Zawahi, the new education secretary, has stated wellbeing will be at the centre of schools’ policy.[v] Yet there is currently a lack of funding in the government’s education recovery plans explicitly targeted at social, mental and emotional health.

Why prioritise social and emotional development?

It is well-established that healthy socio-emotional development is foundational to a successful school life as well as wellbeing in adult life.[vi],[vii] Schools present a unique opportunity to equip young people with the necessary socio-emotional skills given their central role in the lives of children and families. Social and emotional learning (SEL) can be defined as:

“the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions.”[viii]

SEL is underpinned by a preventative philosophy which has both a moral and economic justifications. From an equity perspective, SEL may be particularly beneficial for children from poorer backgrounds as research shows they tend to exhibit worse emotional health and lower self-control than wealthier peers, a gap evident by age three.[ix] From an economic perspective, the Early Intervention Foundation reports that £17bn was spent on ‘picking up the pieces’ of damaging social issues facing young people through late intervention and essential services.[x] Needless to say, these issues are a complex interplay of multiple factors, and SEL does not address their structural causes. However, SEL can help young people in dealing with adverse circumstances in a constructive way, thereby promoting wellbeing and fulfilment. This paper will discuss the evidence around SEL as an early intervention opportunity and highlight some of the key issues around its implementation.

Conceptualising SEL

The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) coined the term ‘social and emotional learning’ in the early 1990s and their definition (above) is the most widely used.[xi] Though CASEL’s definition is fairly precise, its multidimensional nature leads to a variety of approaches and applications. Programmes that nurture a set of tools for learning, ones that promote resilience or others that aim to enhance self-regulation can all come under the umbrella of SEL.[xii],[xiii],[xiv] This presents a barrier to comparing programmes, synthesising findings and identifying effective practice as the approach taken will determine how an intervention is constructed and evaluated. Like the concept of SEL itself, the concepts that fall under the SEL umbrella can be ‘fuzzy’ in nature (e.g. emotional intelligence). This means SEL suffers from ‘jingle-jangle’ construct identity fallacies, ‘jingle’ referring to one term that has multiple definitions and ‘jangle’ referring to different terms being used to describe a largely synonymous concept.[xv] However, the Aspen Institute notes this does not mean SEL is ‘soft’, immeasurable, or faddish, rather that it is multi-faceted and versatile.[xvi]

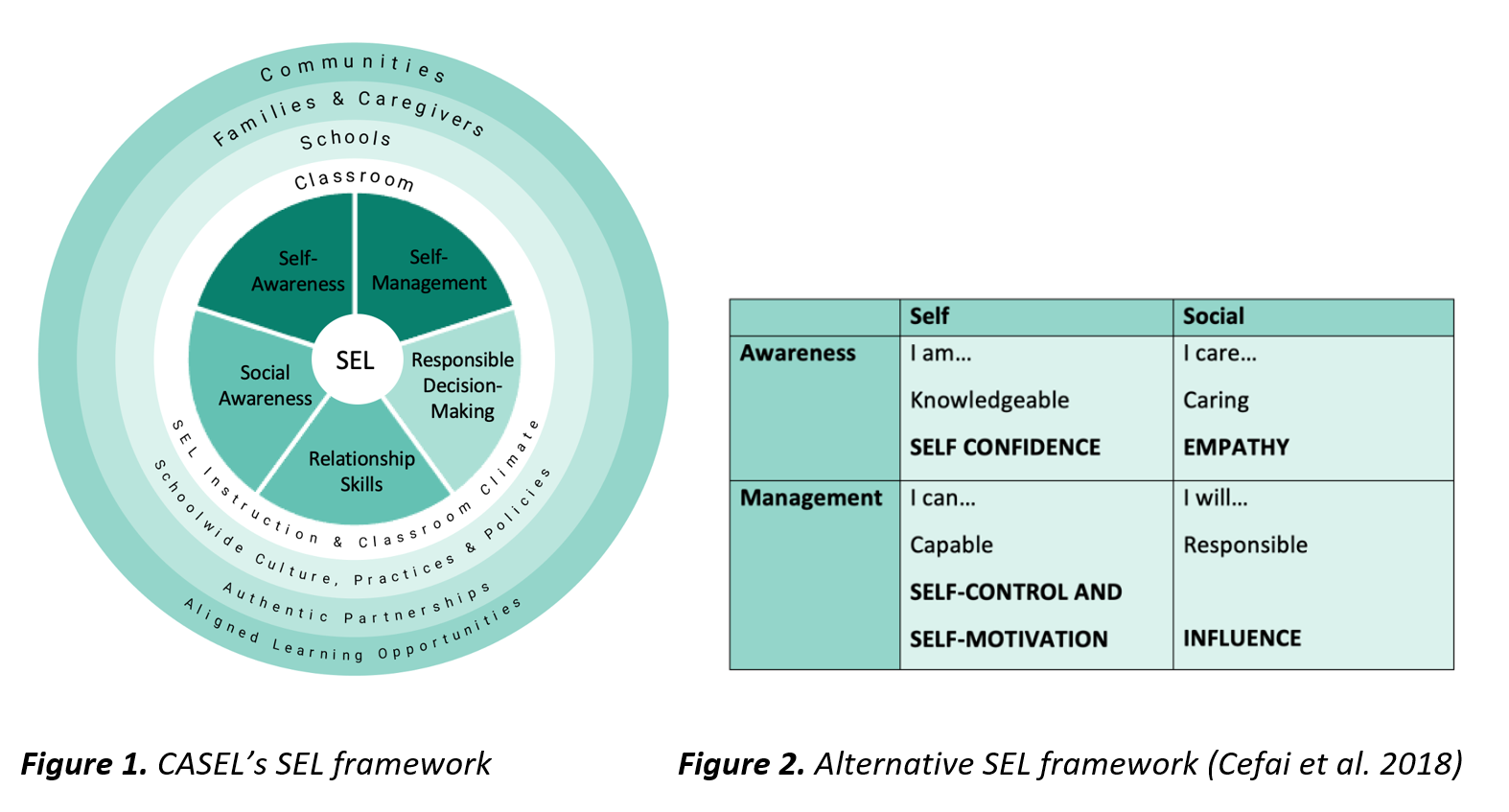

CASEL’s five-point model (Figure 1) encompasses self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. The model is in line with other prominent conceptualisations, for example the OECD’s three-point model of achieving goals, working with others, and managing emotions.[xvii] The most recent model acknowledges that SEL functions within wider contexts such as classroom climate and schoolwide policies, and should be grounded in authentic family and community partnerships.

Though CASEL’s model is the most well-known, other frameworks exist. For example, in a recent international SEL evidence review commissioned by the EU’s Network of Experts working on the Social dimension of Education and Training, authors put forward a framework (Figure 2) which highlights the fundamental similarities in most influential models and definitions (those of CASEL, the OECD (2015), the WHO (1997) and UNICEF (2012)).[xviii],[xix],[xx],[xxi] The framework is a 2×2 matrix consisting of inter-personal (social) and intra-personal (self) dimensions crossed with awareness and management dimensions. While CASEL’s model simply outlines the target skills, this model maps the relationships between specific components (e.g. social awareness) to specific outcomes (e.g. empathy), making it arguably more useful.

What impact does SEL have?

Durlak and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 213 school-based, universal social and emotional learning programmes involving 270,034 kindergarten to secondary school students and assessed impact on:

- social and emotional skills (identifying emotions from social cues, goal setting, perspective taking, interpersonal problem solving, conflict resolution, and decision making);

- attitudes towards self and others (including self-perceptions e.g., self-esteem, self- concept, and self-efficacy);

- school bonding (e.g. attitudes toward school and teachers, and conventional i.e., pro-social beliefs about violence, helping others, social justice, and drug use), positive social behaviour;

- conduct problems;

- emotional distress, and;

- academic performance.[xxii]

They found a significant positive impact on all of these measures, moderated by the programme having ‘SAFE’ (Sequenced, Active, Focused, Explicit) qualities. Impact was also greater for younger students. These findings suggest that well-implemented SEL programmes have the potential to generate positive outcomes, especially if implemented earlier.

An important limitation to the current SEL evidence base is the dearth of longitudinal research. A substantial amount of research demonstrates the value of childhood emotional and social competences for health, education, and wellbeing later in life but only a select number of studies compare the long-term outcomes of those who participated in an SEL intervention to those who did not.[xxiii],[xxiv],[xxv] According to one meta-analysis, only eight percent of SEL studies have follow-ups 18 months or longer post-intervention.[xxvi]

Taylor and colleagues aimed to fill this gap with a meta-analysis of school-based SEL studies that had follow-ups six months or longer post intervention.[xxvii] The authors found that participants who partook in SEL had more positive outcomes on five of the seven outcome variables at follow-up: SEL skills; positive attitudes towards self, others and school; academic performance; emotional distress, and; drug use (effect sizes = .13 – .33). The largest predictor of positive changes in wellbeing at follow-up was social-emotional skills measured directly after the intervention, which include self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making. Though effect sizes may seem modest, as the authors note, in the context of universal promotion or prevention studies even ‘small’ effect sizes can have great practical implications. For example, one intervention had an effect size of .12 but significantly increased school graduation rates by 6 per cent.[xxviii] These are promising indications that SEL interventions can have a long-term positive impact on target skills, and that these skills, in turn, have a positive impact on later well-being. Further longitudinal research, like the SEL project currently undertaken by the OECD, is necessary to further bolster these conclusions.[xxix]

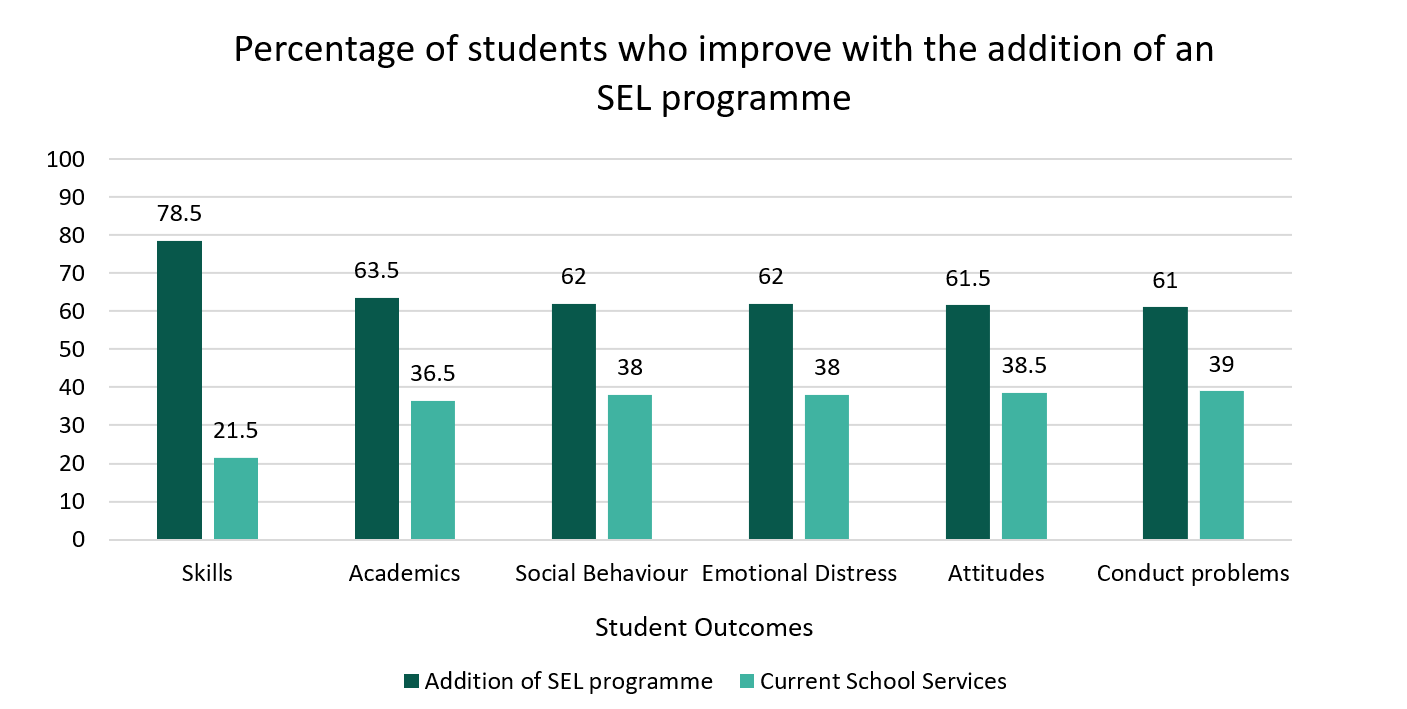

However, outcomes reported in the form of effect sizes run the risk of remaining abstract for school leaders, teachers, and policy makers that want to understand the practical effects of an SEL intervention. CASEL (2019) use the findings of Durlak et al (2011) and Taylor et al (2017) to present the ‘value-added’ based on the proportion of students who show improvements following an SEL intervention (Figure 3):

Figure 3. Percentage of students who improve with the addition of an SEL program (CASEL, 2019)

According to a recent systematic review by the Early Intervention Foundation, SEL programmes are a well-evidenced approach to supporting young people’s mental health.[xxx] Authors found that universal SEL interventions not only enhance young people’s social and emotional skills but reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety in the short-term. Compared with other school-based interventions to enhance young people’s mental health and wellbeing outcomes, SEL programmes have the most evidence to back them up, although more research focused on long-term impact is needed.

Effective practice: what works according to research?

More recent SEL research investigates the common features of effective practice, rather than focusing on the outcome of individual SEL programmes. This area of research, still in its early stages, is a challenging one given the methodological complexity that exists across SEL studies. In their 2019 review of reviews, the EEF identified which factors show the greatest promise in informing school practice.[xxxi] They first identify similarities across SEL interventions such as an explicit curriculum with structured lessons and include a number of pedagogical elements such as role play, cognitive modelling, self-talk, storytelling, written work sheets, teacher instruction, and multi-media stimulus (e.g. videos).

Within these components, however, there is potential for a large amount variation, for example in length, intensity, target age, and sub-domains of SEL targeted. Programmes may focus on one or all five of CASEL’s five sub-domains or may focus on a specific skill that influences multiple SEL domains. For example, some interventions focus solely on nurturing self-regulation, which can help improve relationship skills, responsible decision making, and self-management.[xxxii] By contrast, other programmes might focus exclusively on pro-social behaviour or bullying prevention e.g. Steps To Respect (Low & Van Ryzin 2014; EEF 2019).[xxxiii],[xxxiv] Variation in focus, compounded by differences in implementation strategy, makes it difficult to compare programme efficacy and identify the factors that make one programme more or less successful than another. There are nonetheless promising advances in this area. In a review of international SEL research commissioned by the EU, Cefai and colleagues create a comprehensive model of the practices fundamental to a successful SEL programme.[xxxv] These include:

- Curriculum:

- SEL is not likely to work if it is delivered in fragmented, one-off sessions (like the SEAL programme that was implemented nationally across the UK).[xxxvi] It needs to be integrated into the curriculum.

- ‘SAFE’ programmes:

- Sequenced: a coordinated, step-by-step approach

- Active: learning methods such as role-play with feedback

- Focused: the development of social-emotional skills through devoting sufficient instructional time to it on a regular basis

- Explicit: teaching of clearly identified skills with specific learning objectives, as distinguished from general skill enhancement.[xxxvii]

- Teacher training and support is necessary for school staff to nurture self-efficacy and feel comfortable and confident in adapting the SEL curriculum to respond to the potentially diverse needs of the pupils. A ‘personal-relational’ approach, rather than an ‘informational’ one, is necessary for successful SEL and this relies on sufficient teacher training.

- School climate:

- Interventions are most effective when they use a ‘taught’ (skills instruction) and ‘caught’ (classroom and whole-school climate) approach. Integrating SEL into the classroom climate gives students the opportunity to apply their skills to other areas within the curriculum and observe the skills being practiced by adults and peers. A whole school approach ‘defines the entire school community as the unit of change and involves coordinated action between three interrelated components: (i) curriculum, teaching, and learning; (ii) school ethos and environment; (iii) family and community partnerships’.[xxxviii] It is a deep approach and facilitates more positive interactions between all members of the school.

- Early Intervention:

- Research suggests early intervention could be more effective than later intervention.

- Targeted interventions:

- For children at risk, universal SEL programmes may be more effective if accompanied by targeted interventions.

- Student voice:

- As the key stakeholder, students should take an active role in planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of SEE initiatives at the school.

- Staff competence and wellbeing:

- A whole school approach takes into account the well-being of staff and parents as they are more likely to appropriately support pupils if their own needs and competencies are addressed

- Parental collaboration and education

- Quality implementation and adaptation:

- Adequate and continuous teacher education at pre- service and in-service levels, good planning, and provision of financial and human and resources. Programmes must be responsive to school cultures and students’ needs and interests.

SEL and the pandemic

The pandemic presents a great number of challenges for children and young people, but also provides an opportunity to re-orientate education to better serve pupils’ needs in the long term. CASEL provide an application of each of their SEL subdomains in the current context of the pandemic, along with the international Black Lives Matter movement.[xxxix] They argue that:

- self-awareness is critical for identifying and processing complex emotions in turbulent times, as well as understanding our cultural, racial, and social identities and examining our implicit biases.

- self-management is key to resiliency and feeling a sense of agency.

- social awareness allows us to understand the broader historical and social contexts around the inequalities exacerbated by COVID-19 and ongoing systemic racial inequities.

- relationship skills are essential to maintaining meaningful connections and supporting one another during collective grief and struggle.

- responsible decision-making is important in analysing the consequences of our individual and institutional actions on others’ health and safety and collective well-being.

They also highlight four key SEL practices for supporting well-being as pupils return to school:

- Taking time to cultivate and deepen relationships, build partnerships and plan for SEL.

- Providing support to ensure adults feel empowered, supported and valued by cultivating collective self-care and wellbeing, providing ongoing professional learning and building their capacity to support students.

- Creating safe, supportive, and equitable learning environments that provide all students with an opportunity to feel a sense of belonging, learn about, reflect on and practice SEL.

- Using data as an opportunity to share power by partnering with students, family, staff and the community to learn about students’ and adults’ ongoing needs and strengths.

CASEL’s research demonstrates the potential schools have in supporting young people’s social and emotional well-being in times of crisis as well as responding to pressing global social issues. The Centre for Education and Youth echo this stance, arguing for innovation, adaptation, and reform to education systems, rather than quick fixes, embedding SEL as a central component.[xl] The authors explain that change needs to happen both top-down and bottom-up: policymakers need to provide funding to support social skills and emotional resilience and schools and colleges need to work with evidence-based solutions to build SEL. According to Hall, it is not just the systems that we need to be questioning, but the mindsets of those within the system, as these ultimately determine how the systems operate; as SEL focuses on the holistic development of the human being, he argues that policies, processes, curricula and other systemic mechanisms must put the ‘development of the whole human being at their heart’.[xli] Embedding SEL in curricula, teaching, and learning is also a key component of a whole school approach to mental health, which is the best-evidenced way to positively affect children and young people’s mental health in schools.

UK policy context

From 1997 to 2011 a range of policies promoted SEL, such as the Every Child Matters agenda following the Children’s Act of 2004, which focused on being healthy, staying safe, enjoying and achieving, making a positive contribution, and achieving economic wellbeing. The Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) programme was implemented in two waves from 2005/06 and 2006/07 in both primary and secondary schools in the UK. SEAL was “a comprehensive, whole-school approach to promoting the social and emotional skills that underpin effective learning, positive behaviour, regular attendance, staff effectiveness and the emotional health and well-being of all who learn and work in schools”.[xlii] By 2010, the SEAL programme was being implemented in 90 per cent of UK primary schools and 70 per cent of UK secondary schools.[xliii] As it was designed to give considerable space and flexibility to schools in implementation, effectiveness varied across schools. Unsurprisingly, a DfE evaluation identified that programmes that were implemented with structure and consistency, adhering to the SAFE acronym (discussed above), were more effective than those that did not.[xliv]

A 2015 report by the Early Intervention Foundation, Cabinet Office and Social Mobility & Child Poverty Commission arrived at similar conclusions, stating that SEL provision was patchy, its impact was not being monitored systematically and that a whole-school approach which considered the voices of children was necessary.[xlv] A 2020 report by Nesta argued for the need for greater coherence and clarity in social and emotional skills policy, affording schools greater time, space and resources to develop programmes.[xlvi] The authors call for more evidence on what students need in this field and when an SEL programme be considered effective.

Current provision

Current SEL provision in the UK falls largely under the Personal, Social, Health and Economic (PSHE) curriculum which takes a broad approach and typically includes topics such as emotional health and wellbeing, sex and relationships education, drug and alcohol education, diet and healthy lifestyle education, and safety education. Until 2020, PSHE was a non-statuary subject meaning provision was strongly endorsed but not required within the curriculum. Research suggests PSHE education loses out on timetabling to other more ‘core’ subjects and is often less frequent than the one hour per week suggested by the PSHE association.[xlvii] Ofsted report that in 2013, 40 per cent of schools’ PSHE provision was ‘not yet good enough’.[xlviii] The lack of formal assessment also contributes to the view that PSHE is less important, giving weight to recommendations of formative assessment throughout Social and Emotional Education.[xlix],[l]

Potential pitfalls

Lack of cultural transferability

The meaning of social and emotional development is inextricably linked to societal beliefs and varies as a function of cultural norms, values, and expectations. It is important to consider that most SEL research, as well as the most prominent conceptual frameworks, originate from the USA and are therefore likely to present a US cultural bias. Downes and Cefai suggest that this transferability be achieved by consulting students and parents while the curriculum is being developed, and by intentionally considering the needs of diverse groups.[li] Cefai and colleagues give the RESCUR Surfing the Waves universal resilience curriculum as an example.[lii] The programme includes stories and activities that reflect the diversity of learners, particularly vulnerable children, as well as addressing adversities more common among diverse groups, particularly issues related to bullying, prejudice, discrimination, isolation, lack of friends, language barriers, difficulties in accessing learning, exclusion, or culture mismatch.

In implementing SEL, experts argue that teacher training should promote teachers to be more self-aware of their cultural background, to seek to understand the home background and culture of each child with open-mindedness and to adopt an attitude that regards the diversity of learners as an opportunity for all children to enrich and extend their learning.[liii],[liv]

Social conformity and control

Researchers note that in the OECD’s 2015 report ‘Skills for Social Progress’, the three most emphasised skills are conscientiousness, sociability and emotional stability, stating these are have the most positive effect on life outcomes.[lv],[lvi] Here, the authors question how ‘success’ is being defined: the report equates it with as a rise in socio-economic level and access to the labour market, and a successful student as one who is conscientious, socially able and has self-control. Authors argue that this could reflect a conception of the ideal student as one who does not rock the boat, and SEL a tool to encourage conformity and control. In their review of SEL in early care settings, Blewitt and colleagues echo this with the finding that programmes disproportionately focused on social competence as opposed to intra-personal skills.[lvii]

‘Surface-level’ approaches linked to accountability pressures

Cefai and colleagues argue that policy documents published by EU member states since 2011 have recognised the central importance of emotional and relational components of education but have left the curriculum and policy details largely implicit.[lviii] In doing so, they avoid being criticised for neglecting social-emotional dimensions while not taking necessary action to prioritise it. Whilst the evident lack of concrete action to ensure SEL provision in the UK paints a similar picture, one recent noteworthy change in the UK SEL landscape was the addition of the ‘personal development’ category within Ofsted’s school inspection framework.[lix],[lx] This category assesses schools on the extent to which they nurture resilience, confidence and mental health. This development addresses the EIF’s concerns that key operational drivers in the education sector, such as Ofsted, do not prioritise socioemotional learning.[lxi]

However, as stated by Banerjee and colleagues, the pressure of relentlessly pursuing better attainment standards mean that a range of policies, strategies, and initiatives can overwhelm schools such that well-intentioned SEL programmes are implemented in an “uncoordinated, piecemeal, and incomplete way.”[lxii] This is perhaps especially true given the 2015 curriculum reforms, which placed even more academic pressure on schools. As the research reviewed suggests, SEL provision is most likely to be successful if a whole-school approach is taken, where the schools adopt and integrate SEL values across the curriculum. Whilst Ofsted’s new criteria might represent a step to prioritising SEL, without adequate support systems that provide ‘greater time, space and resources’ for SEL, this may not do much more than place an extra burden on schools and lead to a superficial ‘tick the box’ approach.[lxiii]

Conclusion

Whilst the complexity and versatility of SEL can present challenges for establishing the factors that should be kept consistent across programmes, research has made promising advances in identifying what constitutes effective practice. Under the current backdrop of the pandemic, SEL’s value in responding to the mental and emotional challenges faced by young people is more pronounced than ever. Adopting a whole-school ‘SAFE’ approach is currently lacking in the UK’s PSHE curriculum, though upgrading its status to a statutory subject, as well as the addition of the ‘personal development’ section of Ofsted’s inspection framework are potentially promising advances.

There are multiple potential pitfalls to effective SEL practice including its cultural biases, the potential for it to be used as a method of social conformity and ‘surface-level’ approaches resulting from increased accountability and lack of sufficient systematic support. Effective SEL relies on embedding principles further upstream, such that policies, processes and curricula, and the mindsets of those determining them, centre the holistic development of children and young people.

Finally, it is important to mention that SEL approaches are more likely to work within broader structures or systems that promote mental health and wellbeing. Particularly when considering SEL as a tool for promoting equity, placing responsibility on young people living in poverty and exclusion to overcome its social and emotional effects, without addressing structural causes, is contrary to the preventative philosophy behind social and emotional education.

[i] “Mental Health”. 2021. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/mental-health.htm.

[ii] OECD. 2021a. “Supporting Young People’S Mental Health Through The COVID-19 Crisis”. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). OECD. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1094_1094452-vvnq8dqm9u&title=Supporting-young-people-s-mental-health-through-the-COVID-19-crisis&_ga=2.97411103.1464833276.1631195864-511934724.1628598788.

[iii] NHS Digital. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2020: Wave 1 follow-up to the 2017 survey. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2020-wave-1-follow-up

[iv] NHS England, Mental Health, Children and young people. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/cyp/

[v] NAHT. 2021. “Tutoring Is A Top Priority For Education Recovery – But Not Via The National Tutoring Programme, Say School Leaders”. NAHT. https://naht.org.uk/NAHT-Edge/ArtMID/694/ArticleID/1009/Tutoring-is-a-top-priority-for-education-recovery-but-not-via-the-National-Tutoring-Programme-say-school-leaders.

[vi] Jones, Damon E., Mark Greenberg, and Max Crowley. “Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness.” American journal of public health 105, no. 11 (2015): 2283-2290.

[vii] Sorrenti, Giuseppe, Ulf Zölitz, Denis Ribeaud, and Manuel Eisner. “The causal impact of socio-emotional skills training on educational success.” University of Zurich, Department of Economics, Working Paper 343 (2020).

[viii] CASEL. 2020. “What Is SEL?”. CASEL. https://casel.org/what-is-sel/.

[ix] Early Intervention Foundation. 2015. “Social And Emotional Learning: Skills For Life And Work”. Early Intervention Foundation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411489/Overview_of_research_findings.pdf.

[x] Early Intervention Foundation. 2015. “Social And Emotional Learning: Skills For Life And Work”. Early Intervention Foundation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411489/Overview_of_research_findings.pdf.

[xi] Department for Education. 2010. “Social And Emotional Aspects Of Learning (SEAL) Programme In Secondary Schools: National Evaluation”. London: Department for Education.

[xii] Banerjee, Robin, Katherine Weare, and William Farr. “Working with ‘Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning’(SEAL): Associations with school ethos, pupil social experiences, attendance, and attainment.” British educational research journal 40, no. 4 (2014): 718-742.

[xiii] DEECD. 2014. “Building Resilience In Children And Young People”. Victoria: Melbourne Graduate School of Education.

[xiv] McKown, Clark, Laura M. Gumbiner, Nicole M. Russo, and Meryl Lipton. “Social-emotional learning skill, self-regulation, and social competence in typically developing and clinic-referred children.” Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 38, no. 6 (2009): 858-871.

[xv] Education Endowment Foundation. 2019. “Primary Social And Emotional Learning: Evidence Review”. London: Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Social_and_ Emotional_Learning_Evidence_Review.pdf.

[xvi] The Aspen Institute. 2017. “The Evidence Base For How We Learn: Supporting Students’ Social, Emotional, And Academic Development”.

[xvii] OECD. 2015. “Skills For Social Progress: The Power Of Social And Emotional Skills”. OECD Skills Studies. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

[xviii] Cefai, Carmel, Paul Bartolo, Valeria Cavioni, and Paul Downes. 2018. “Strengthening Social And Emotional Education As A Core Curricular Area Across The EU. A Review Of The International Evidence”. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AR3_Full-Report_2018.pdf.

[xix] WHO. 1997. “Life Skills Education For Children And Adolescents In Schools”. Geneva: WHO. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/63552/WHO_MNH_PSF_93.7A_Rev.2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[xx] United Nations Children’s Fund – UNICEF (2012). Global Life Skills Education Evaluation: Draft Final Report. London: Education for Change Ltd.

[xxi] OECD. 2015. “Skills For Social Progress: The Power Of Social And Emotional Skills”. OECD Skills Studies. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

[xxii] Durlak, Joseph A., Roger P. Weissberg, Allison B. Dymnicki, Rebecca D. Taylor, and Kriston B. Schellinger. “The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta‐analysis of school‐based universal interventions.” Child development 82, no. 1 (2011): 405-432.

[xxiii] Hawkins, J. David, Rick Kosterman, Richard F. Catalano, Karl G. Hill, and Robert D. Abbott. “Effects of social development intervention in childhood 15 years later.” Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 162, no. 12 (2008): 1133-1141.

[xxiv] Jones, Damon E., Mark Greenberg, and Max Crowley. “Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness.” American journal of public health 105, no. 11 (2015): 2283-2290.

[xxv] Taylor, Rebecca D., Eva Oberle, Joseph A. Durlak, and Roger P. Weissberg. “Promoting positive youth development through school‐based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta‐analysis of follow‐up effects.” Child Development 88, no. 4 (2017): 1156-1171.

[xxvi] Wigelsworth, Michael, Ann Lendrum, J. Oldfield, Adam Scott, I. Ten Bokkel, K. Tate, and Carl Emery. “The impact of trial stage, developer involvement and international transferability on universal social and emotional learning programme outcomes: A meta-analysis.” Cambridge Journal of Education 46, no. 3 (2016): 347-376.

[xxvii] Taylor, Rebecca D., Eva Oberle, Joseph A. Durlak, and Roger P. Weissberg. “Promoting positive youth development through school‐based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta‐analysis of follow‐up effects.” Child Development 88, no. 4 (2017): 1156-1171.

[xxviii] Bradshaw, Catherine P., Jessika H. Zmuda, Sheppard G. Kellam, and Nicholas S. Ialongo. “Longitudinal impact of two universal preventive interventions in first grade on educational outcomes in high school.” Journal of educational psychology 101, no. 4 (2009): 926.

[xxix] OECD. 2021b. “OECD Survey On Social And Emotional Skills”. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/social-emotional-skills-study/.

[xxx] Early Intervention Foundation. Adolescent mental health: A systematic review on the effectiveness of school-based interventions.

[xxxi] Education Endowment Foundation. 2019. “Primary Social And Emotional Learning: Evidence Review”. London: Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Social_and_ Emotional_Learning_Evidence_Review.pdf.

[xxxii] Pandey, Anuja, Daniel Hale, Shikta Das, Anne-Lise Goddings, Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, and Russell M. Viner. “Effectiveness of universal self-regulation–based interventions in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” JAMA pediatrics 172, no. 6 (2018): 566-575.

[xxxiii] Low, Sabina, and Mark Van Ryzin. “The moderating effects of school climate on bullying prevention efforts.” School psychology quarterly 29, no. 3 (2014): 306.

[xxxiv] Education Endowment Foundation. 2019. “Primary Social And Emotional Learning: Evidence Review”. London: Education Endowment Foundation. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Social_and_ Emotional_Learning_Evidence_Review.pdf.

[xxxv] Cefai, Carmel, Paul Bartolo, Valeria Cavioni, and Paul Downes. 2018. “Strengthening Social And Emotional Education As A Core Curricular Area Across The EU. A Review Of The International Evidence”. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AR3_Full-Report_2018.pdf.

[xxxvi] Department for Education. 2010. “Social And Emotional Aspects Of Learning (SEAL) Programme In Secondary Schools: National Evaluation”. London: Department for Education.

Durlak, Joseph A., Roger P. Weissberg, Allison B. Dymnicki, Rebecca D. Taylor, and Kriston B. Schellinger. “The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta‐analysis of school‐based universal interventions.” Child development 82, no. 1 (2011): 405-432.

[xxxviii] Goldberg, Jochem M., Marcin Sklad, Teuntje R. Elfrink, Karlein MG Schreurs, Ernst T. Bohlmeijer, and Aleisha M. Clarke. “Effectiveness of interventions adopting a whole school approach to enhancing social and emotional development: a meta-analysis.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 34, no. 4 (2019): 755-782.

[xxxix] CASEL. 2019. “The Practical Effects Of An SEL Intervention”. CASEL. https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Practical-Benefits-of-SEL-Program.pdf.

[xl] Centre for Education and Youth. 2020. “Social And Emotional Learning And The New Normal”. Centre for Education and Youth. https://cfey.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Social-emotional-learning-report-A4-digi.pdf.

[xli] Hall, Ross. 2020. “Building The Right Mindset”. Presentation, A summary of The Centre for Education and Youth and STiR Education’s Roundtable, 2020.

[xlii] Department for Education. 2010. “Social And Emotional Aspects Of Learning (SEAL) Programme In Secondary Schools: National Evaluation”. London: Department for Education.

[xliii] CASCAID. 2020. “Social-Emotional Learning Standards In The UK & US | CASCAID”. CASCAID. https://cascaid.co.uk/social-emotional-learning/standards/.

[xliv] Department for Education. 2010. “Social And Emotional Aspects Of Learning (SEAL) Programme In Secondary Schools: National Evaluation”. London: Department for Education.

[xlv] Feinstein, L. “Social and emotional learning: Skills for life and work.” Early Intervention Foundation (2015).

[xlvi] Nesta. 2020. “Developing Social And Emotional Skills. Education Policy And Practice In The UK Home Nations”. London: Nesta. https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/Developing_Social_and_Emotional_Skills.pdf.

[xlvii] Formby, Eleanor, and Claire Wolstenholme. “‘If there’s going to be a subject that you don’t have to do…’Findings from a mapping study of PSHE education in English secondary schools.” Pastoral Care in Education 30, no. 1 (2012): 5-18.

[xlviii] Ofsted. 2013. “Not Yet Good Enough: Personal, Social, Health And Economic Education In Schools”. London: Ofsted.

[xlix] Formby, Eleanor, and Claire Wolstenholme. “‘If there’s going to be a subject that you don’t have to do…’Findings from a mapping study of PSHE education in English secondary schools.” Pastoral Care in Education 30, no. 1 (2012): 5-18.

[l] Cefai, Carmel, Paul Bartolo, Valeria Cavioni, and Paul Downes. 2018. “Strengthening Social And Emotional Education As A Core Curricular Area Across The EU. A Review Of The International Evidence”. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AR3_Full-Report_2018.pdf.

[li] Downes, Paul, and Carmel Cefai. How to prevent and tackle bullying and school violence: Evidence and practices for strategies for inclusive and safe schools. Publications Office of the European Union, 2016.

[lii] Cefai, Carmel, Paul Bartolo, Valeria Cavioni, and Paul Downes. 2018. “Strengthening Social And Emotional Education As A Core Curricular Area Across The EU. A Review Of The International Evidence”. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AR3_Full-Report_2018.pdf.

[liii] Cefai, Carmel, Paul Bartolo, Valeria Cavioni, and Paul Downes. 2018. “Strengthening Social And Emotional Education As A Core Curricular Area Across The EU. A Review Of The International Evidence”. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AR3_Full-Report_2018.pdf.

[liv] PPMI. 2017. “Preparing Teachers for Diversity: The Role of Initial Teacher Education – Final Report to DG Education, Youth, Sport and Culture of the European Commission.”

[lv] Boland, Neil, “Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills” Review of Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills, by OECD, The International Journal of Emotional Education 7,1 (2015): 84-89. www.um.edu.mt/cres/ijee

[lvi] OECD. 2015. “Skills For Social Progress: The Power Of Social And Emotional Skills”. OECD Skills Studies. OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

[lvii] Blewitt, Claire, Amanda O’Connor, Heather Morris, Tamara May, Aya Mousa, Heidi Bergmeier, Andrea Nolan, Kylie Jackson, Helen Barrett, and Helen Skouteris. “A systematic review of targeted social and emotional learning interventions in early childhood education and care settings.” Early Child Development and Care (2019): 1-29.

[lviii] Cefai, Carmel, Paul Bartolo, Valeria Cavioni, and Paul Downes. 2018. “Strengthening Social And Emotional Education As A Core Curricular Area Across The EU. A Review Of The International Evidence”. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AR3_Full-Report_2018.pdf.

[lix] CASCAID. 2020. “Social-Emotional Learning Standards In The UK & US | CASCAID”. CASCAID. https://cascaid.co.uk/social-emotional-learning/standards/.

[lx] Ofsted. 2019. “Education Inspection Framework”. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/education-inspection-framework/education-inspection-framework.

[lxi] Early Intervention Foundation. 2015. “Social And Emotional Learning: Skills For Life And Work”. Early Intervention Foundation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/411489/Overview_of_research_findings.pdf.

[lxii] Banerjee, Robin, Katherine Weare, and William Farr. “Working with ‘Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning’(SEAL): Associations with school ethos, pupil social experiences, attendance, and attainment.” British educational research journal 40, no. 4 (2014): 718-742.

[lxiii] Nesta. 2020. “Developing Social And Emotional Skills. Education Policy And Practice In The UK Home Nations”. London: Nesta. https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/Developing_Social_and_Emotional_Skills.pdf.