Just over a year ago, Boris Johnson campaigned for the leadership of the Conservative Party on an agenda to ‘get Brexit done’ and to address the ‘opportunity gap’ between different parts of the United Kingdom. [1] The narrative through the opening months of his premiership was underpinned by his belief that ‘talent and genius are uniformly distributed throughout the country [but that] opportunity is not.’[2] It came with a commitment to significant additional spending on schools in England, particularly in schools that had historically received lower levels of per pupil funding. Less than two months in, that commitment was met with the September’s spending round announcing increases amounting to just over £7bn a year in cash terms by 2022-23.

Of course, the period that has followed is hardly one of a government quietly getting on with the routine business of running the country. Parliamentary deadlock over Brexit leading to a December general election now feels like a period of normality in comparison with the Covid-19 pandemic.

But the routine things do carry on, and last month the Department for Education set out funding arrangements for schools for 2021-22 including notional allocations for individual schools under the National Funding Formula (NFF). The allocations are notional since the role for local authorities and local funding formulae to determine actual allocations remains. The so called ‘hard NFF’ – where funding for individual schools are set centrally by the DfE – is still at least a year away. So, schools will not necessarily see the amounts that have been announced, but they do illustrate where the government’s priorities are.

In 2021-22, total Schools Block funding will be £38.8bn, representing a cash increase of £1.4bn on allocations for 2020-21, or 3.1 per cent on a per pupil basis – just over one per cent after allowing for inflation.[3] Note that this is the increase after including the Teachers’ Pay Grant (new funding which is intended to pay for higher starting salaries and pay increases for teachers) and the Teachers’ Pension Employer Contribution Grant within the baseline, but does not include the £7.9bn delivered through the High Needs Block nor the Pupil Premium.

The latest round of funding announcements continues to reflect the government’s commitment to ‘level-up’ funding. We have previously expressed concerns about this approach. Levelling up funding means, by definition, directing funding towards schools that have previously been funded at a lower rate. These schools will, on average, have fewer pupils that attract additional funding through the NFF – pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, pupils with low prior attainment, pupils with English as a second language – so a key question is how is the funding formula affecting different pupils.

This is perhaps even more important now than it was a year ago. There is emerging evidence of the disproportionate effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on different groups, with pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds being less likely to have access to a set-up that is conducive to distance learning and, on average, spending less time on home learning than their more affluent peers.[4]

The NFF sets out the amount of additional funding that a particular characteristic attracts – for example, being eligible for free school meals attracts an additional £460 per year. But it does not show us either how these factors interact, nor how pupils without those characteristics benefit from being in schools with pupils that do. Allocations are made at school level and funding is not ringfenced for particular pupils, so for example the per pupil funding for a non-FSM pupil in a high-FSM school will be higher than for a non-FSM pupil elsewhere.

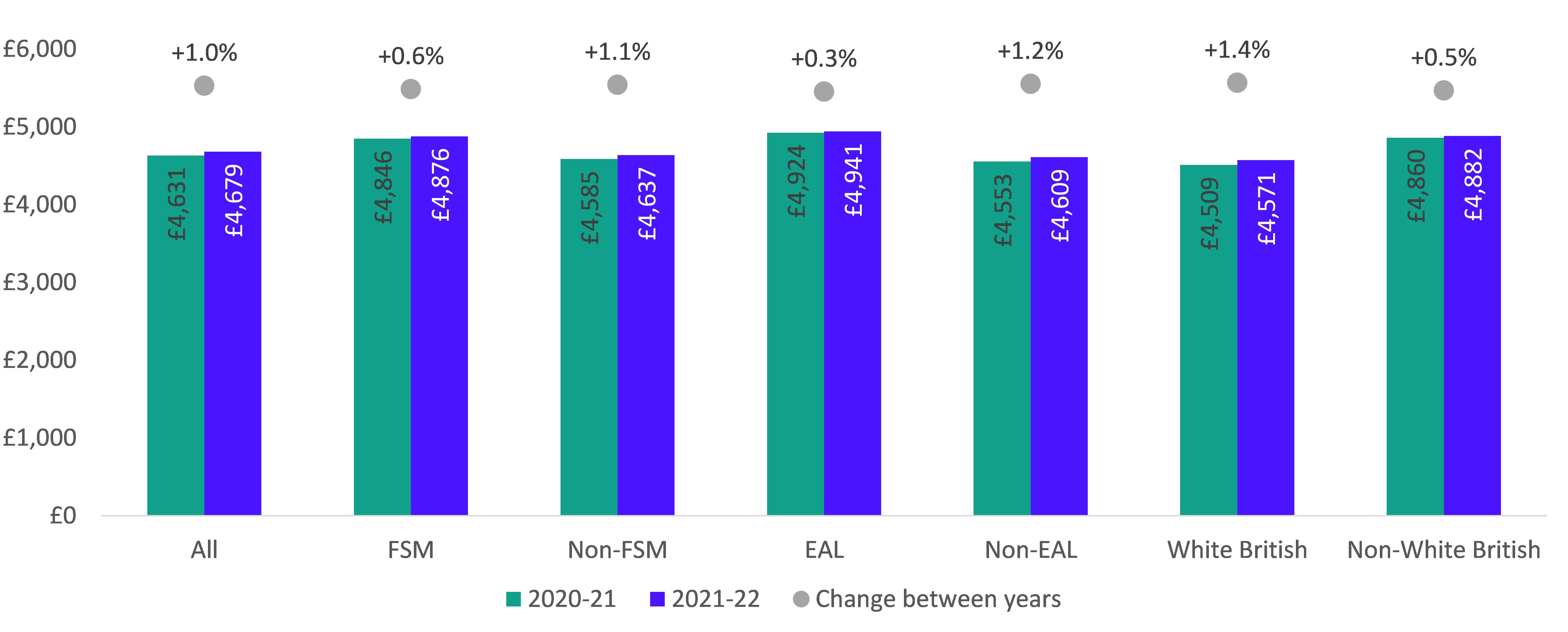

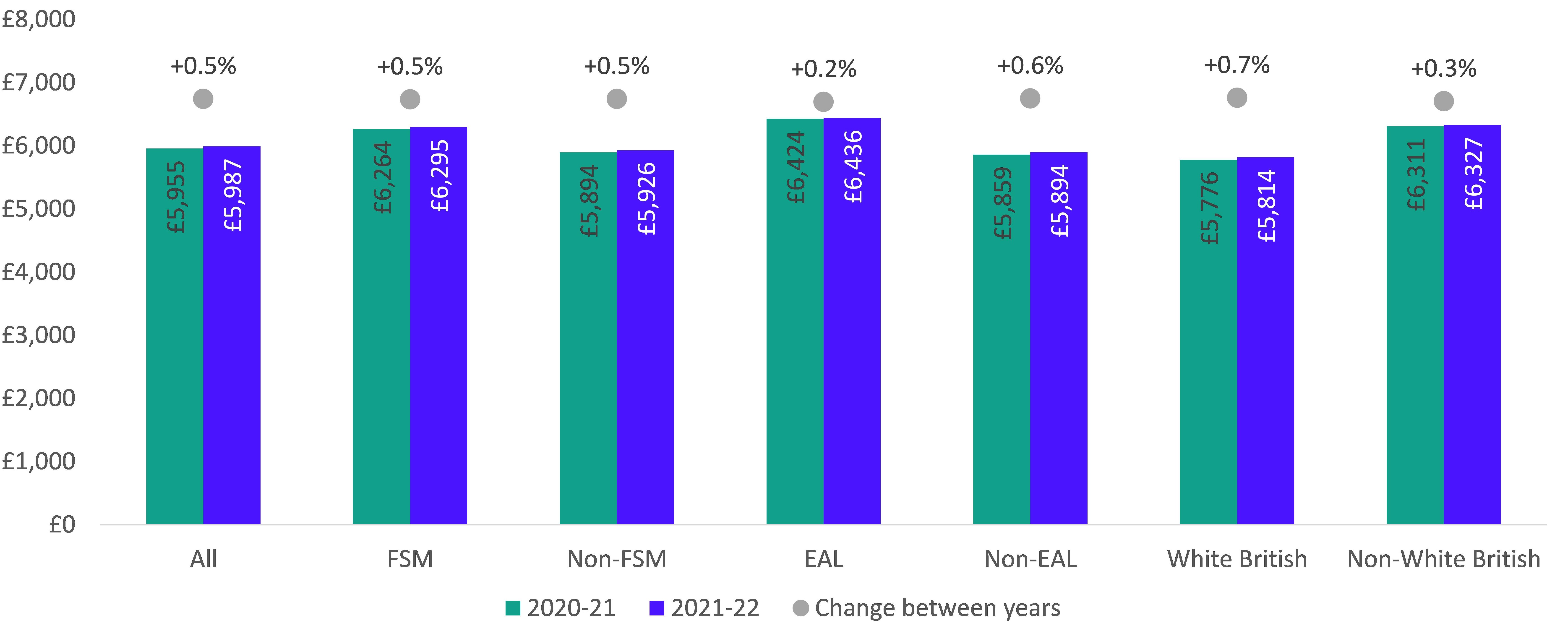

Instead we can use the published school level allocations, linked with pupil characteristics data from the school census, to calculate the average funding per pupil by these characteristics. These are shown in for primary schools in Figure 1, and for secondary schools in Figure 2.

On average, amongst primary schools:

- pupils eligible for free school meals will receive around £240 more than non-FSM pupils;

- pupils with English as an additional language will receive around £330 more than non-EAL pupils; and

- non-White British pupils will receive around £310 more than White-British pupils.

The equivalent figures for pupils in secondary schools are £370, £540, and £510 respectively. These differences result from a combination of pupil characteristics within the NFF, the areas of the country with such pupils (higher funded London for example has a disproportionately high number of EAL pupils), and the historic funding of the schools that they attend.

Figure 1: Change in per pupil funding by pupil characteristics between 2020-21 and 2021-22 – primary schools (in 2021-22 prices)

Figure 2: Change in per pupil funding by pupil characteristics between 2020-21 and 2021-22 – secondary schools (in 2021-22 prices)

But, crucially, if we compare funding in 2021-22 with those in 2020-21, we find that these differences are falling. In other words, these groups will be receiving smaller increases than other pupils this year. Pupils eligible for free school meals in primary schools will receive increases of 0.6 per cent in comparison to 1.1 per cent for non-FSM pupils, after controlling for inflation.

There are similar differences when we examine other characteristics. In primary schools, funding for White-British pupils will increase at over twice the rate of non-White British pupils, and non-EAL pupils will receive increases that are three times the rate of EAL pupils.

The patterns are less clear in secondary schools. Amongst secondary school pupils, funding for FSM and non-FSM pupils will increase at similar rates but there remain differences between EAL and non-EAL pupils and between White British and non-White British pupils (though the increases for all groups are small).

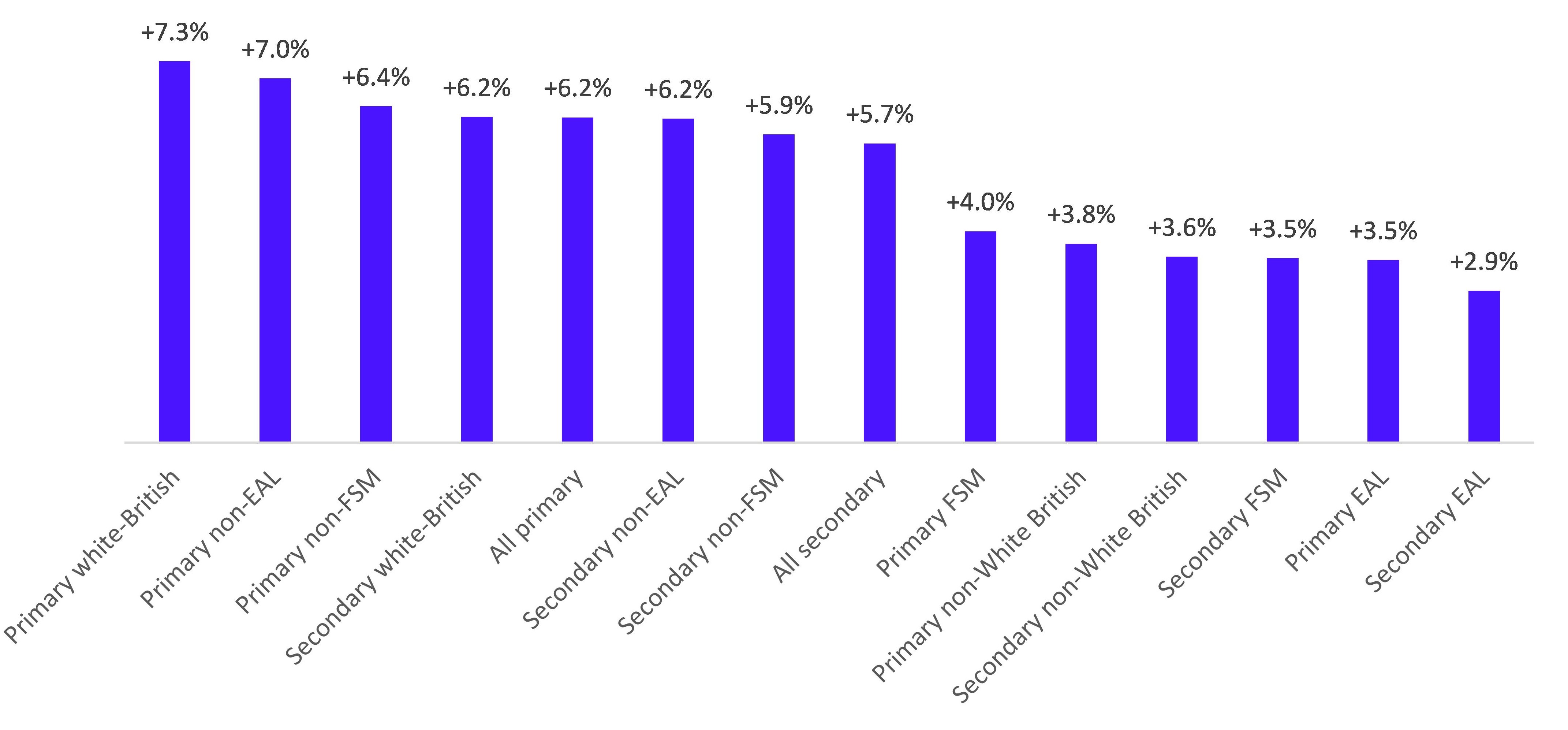

This is not a one-year issue. In Figure 3 we compare the per pupil funding in 2021-22 to those in 2017-18, the last year before the introduction of the NFF.[5] We find that:

- pupils that have English as an additional language have received increases at half the rate of other pupils in both primary and secondary schools;

- pupils from non-White British backgrounds have received increases at just over half the rate of other pupils in both primary and secondary schools; and

- pupils who are eligible for free school meals have received increases at around two-thirds of the rate of non-FSM pupils.

Figure 3: Change in per pupil funding by pupil characteristics between 2017-18 and 2021-22 (real terms)

The NFF is built on the premise that no matter where they go to school, pupils with the same characteristics should receive the same level of funding. From a perspective of fairness this is a perfectly laudable aim – though, as ever, achieving a funding system that is fair is not the same as achieving a funding system in which schools receive the right amount of funding for the challenges that they face.

But the approach to levelling up funding is having a distorting effect on that aim. In order to meet its commitment to achieve minimum levels of funding in both primary and secondary schools the government includes an additional factor in the NFF to essentially make up the difference if the pupil level allocations are not sufficient to meet these minimums.[6],[7]

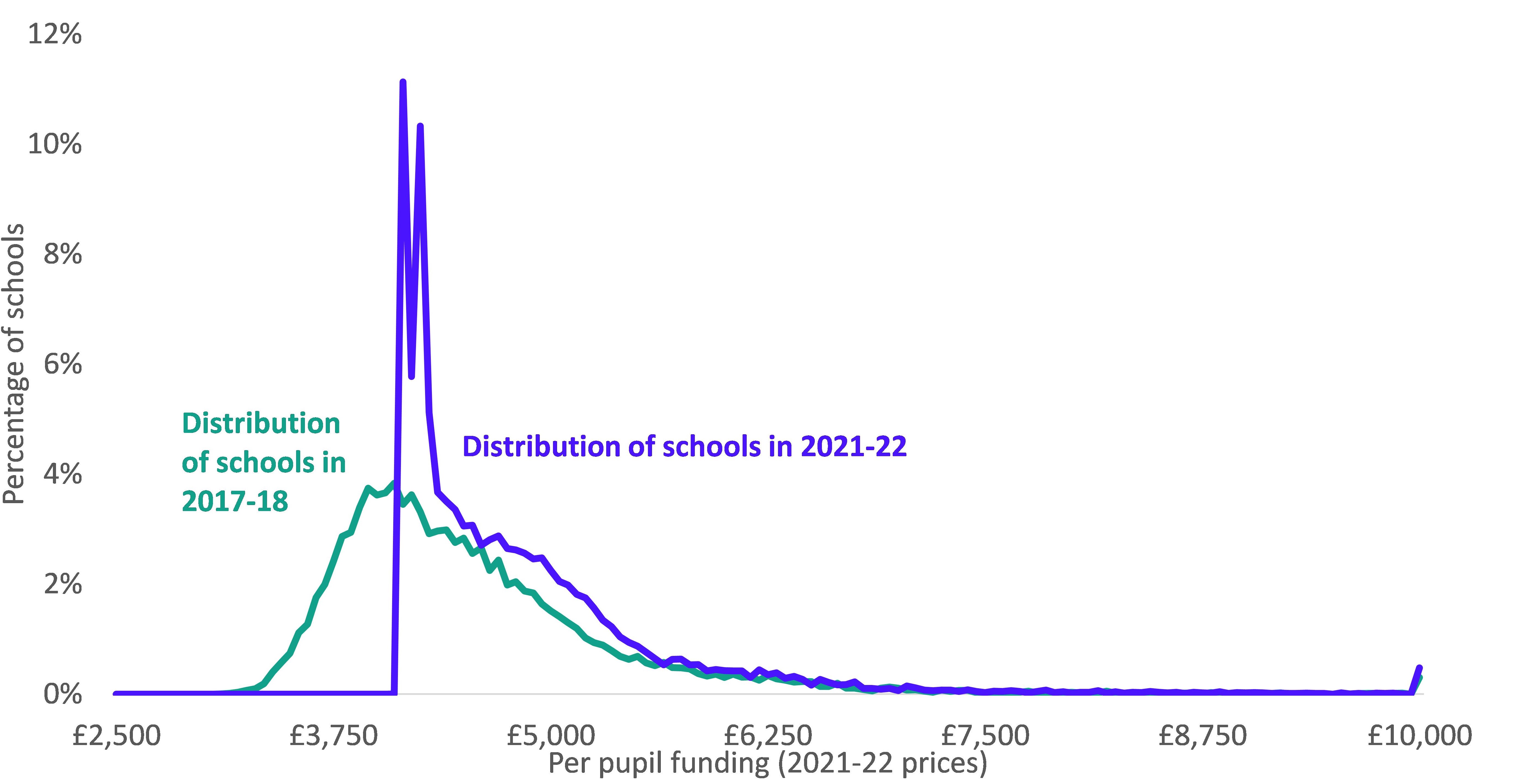

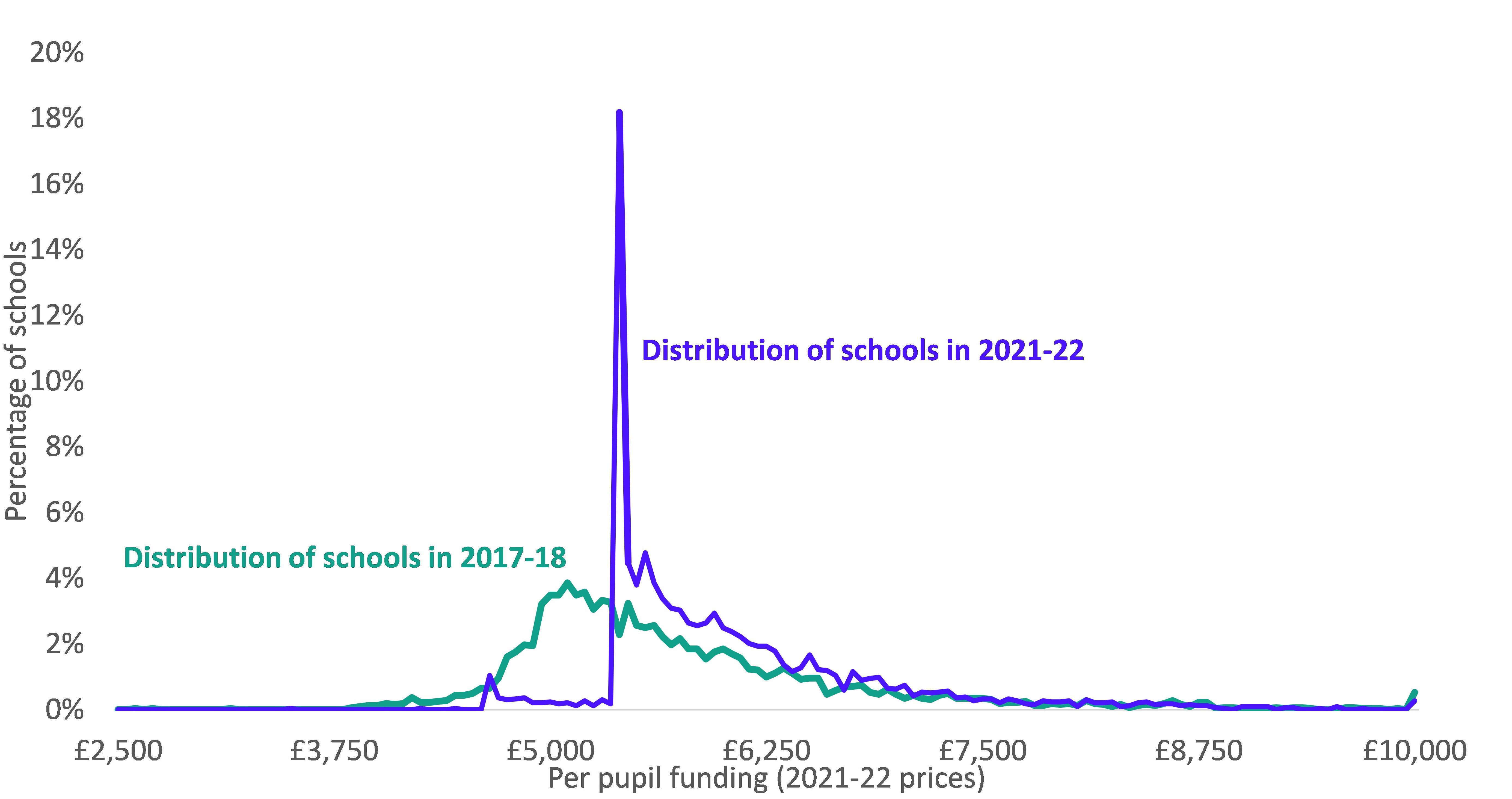

Figures 4 and 5 show the distribution of per pupil funding at school level in 2017-18 (the final year before the NFF) and in 2021-22. The ‘squeezing-up’ of the distribution is clear to see: with a large number of schools simply receiving the minimum level of funding, around 1 in 5 schools will receive funding at, or close to, the minimum funding level. Where funding has been increased to reach these levels, it means that pupils in these schools are receiving more than pupils with the same characteristics in otherwise more highly funded schools.

Figure 4: Distribution of school level per pupil funding in 2017-18 and 2021-22 in primary schools (2021-22 prices)

Figure 5: Distribution of school level per pupil funding in 2017-18 and 2021-22 secondary schools (2021-22 prices)

Conclusion

The school funding system in England remains progressive and pupils from low income backgrounds continue to attract more funding than their more affluent peers. This reflects the challenges that these schools face and the need to address the fact that pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds end compulsory education 18 months behind their peers.

But the link between funding and pupil need is being weakened by a system of levelling up which directs a proportion of additional funding towards schools with historically lower levels of funding – these schools will typically (though by no means exclusively) be serving schools in more affluent areas.

Levelling up is not the only way in which this has happened in recent years. The Teacher Pay Grant, which will be used for the final time in 2020-21, has been linked to pupil numbers, not to the costs facing schools. This ignores the fact that schools operating in more challenging circumstances tend to employ more teachers and so will face higher costs from increased salaries. In 2021-22 this will be incorporated into core schools funding. It is being added to the basic per pupil funding allocations, meaning it continues to be linked with pupil numbers not their characteristics, as well as the minimum funding level itself. If the funding had been distributed across other factors it would perhaps have been better linked with need, but it would also mean that more funding would have been needed to ‘level-up’. It’s difficult to determine the ideal approach within these constraints.

The Department for Education will no doubt point to three ways in which disadvantaged pupils will benefit over the coming years outside of core schools funding. The first is an increase to the Pupil Premium from April 2020. This is, however, only an inflation level increase and this is still well below historic levels in real terms, having been held largely flat for a number of years. The primary pupil premium has in real terms lost 7 per cent of its value, and the secondary pupil premium 8 per cent of its value, since 2015. The second is the £650m of additional funding in the system by way of Covid-19 catch-up funding, but again this is being linked with pupil numbers with no attempt to reflect the differing needs of pupils.

The final way is the £350m that is being used to subsidise the cost of tutors for disadvantaged pupils in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, of which £96m will be directed towards post-16 education. Additional funding is welcome, but this is a subsidy, not additional funding to schools. Schools will only be able to access that support if they are able to meet their part of the cost.

Even before the extraordinary circumstances that schools have faced in 2020 there was emerging evidence that the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers was at risk of widening. The crisis is likely to have increased that risk and the challenge of narrowing the gap just got harder.

The government’s approach to funding does not appear to be taking that challenge seriously.

[1] The Spectator, ‘Full text: Boris Johnson launches his Tory leadership campaign’, June 2019

[2] B. Johnson, ‘The Conservative and Unionist Party manifesto 2019’, November 2019

[3] Department for Education, ‘National funding formula tables for schools and high needs: 2021 to 2022’, July 2020

[4] Institute for Fiscal Studies, ‘Learning during the lockdown: real-time data on children’s experiences during home learning’, May 2020

[5] To do this, we have estimated per pupil funding by characteristics in 2017-18 by using the published baseline figures for the 2018-19 NFF and linked with data from the January 2017 School Census. School funding allocations are primarily based on the October census which may introduce some discrepancies with actual allocations. However, we believe the relative amounts between different groups should be robust to this difference.

[6] The minimum funding levels in 2021-22 will be £4,180 in primary schools, £5,215 for Key Stage 3 pupils, and £5,715 for Key Stage 4 pupils. These are higher than the previously announced rates to allow for the incorporation of the Teachers’ Pay Grant and the Teachers’ Pension Employer Contribution Grant

[7] In addition to raising the minimum funding levels, the government has also greatly increased the ‘sparsity’ factor this year which will benefit small remote schools and disproportionately benefit some groups of pupils.