In recent years, public debates on gender have increasingly focused on boys and men falling behind. Data from Western countries consistently show long-term gaps in educational attainment, university enrolment, and degree outcomes. Boys are behind girls on every official child development measure on starting school, and continue to trail girls’ attainment (on headline measures) as they progress through compulsory education. Research highlights the broader consequences, including declining marriage rates and poorer adult health outcomes for men.

Yet some recent studies suggest that the trend of boys falling behind girls might be in reverse. EPI’s recent annual report shows that, in England, boys are catching up with girls in GCSE English and maths, with the gap narrowing to 4.5 months in 2023, the smallest gap since 2011. Interestingly, we find that it is since the onset of the Covid 19 pandemic that the gender gap has shrunk the most: between 2019 and 2023, the GCSE gap markedly narrowed by more than three months.[1] This reduction in the gap is one of the biggest post-pandemic reductions across all of the attainment gaps that we considered. This reflects not only boys catching up but girls’ performance declining in absolute terms.

Separate studies also find that learning loss during the pandemic affected girls more than boys and international research shows boys are pulling ahead once again in maths and science.

It’s too early to tell if these findings indicate a long-term reversal of the trend we’ve seen over the last decade — but they raise the question: how worried should we be about girls?

Girls’ outperformance of boys in education has perhaps masked the emergence of other concerning trends, primarily their worsening mental health and wellbeing.

As we explore in the section below, several indicators suggest the wellbeing of girls is deteriorating. This raises the question of whether these relatively poor wellbeing trends are now having an impact on girls’ educational outcomes too?

How have indicators of girls’ and boys’ wellbeing changed in recent years?

We’ll focus on data covering three broad areas of wellbeing, drawing on a range of data sources. The first area is mental health:

- Girls are more likely to have had a diagnosable mental health issue and to have deliberately self-harmed compared to boys: In 2023, a third of adolescent girls had a likely diagnosable mental health issue, compared with 12 per cent of boys. A fifth (20 per cent) of 16-year-old boys and half (49 per cent) of girls report having deliberately self-harmed, with a rise over 2018-2022 significantly more pronounced among girls (+14 percentage points) than boys (+4 percentage points).

- Girls are less likely to be considered as ‘thriving’: There is a gender gap in the proportion of young people classified as ‘thriving’ which has widened over 2018-2022. Whilst the proportion among boys has fallen (from 79 to 74 per cent), the decrease is much sharper among girls (from 72 to 56 per cent, the lowest proportion since the start of the series in 2002).

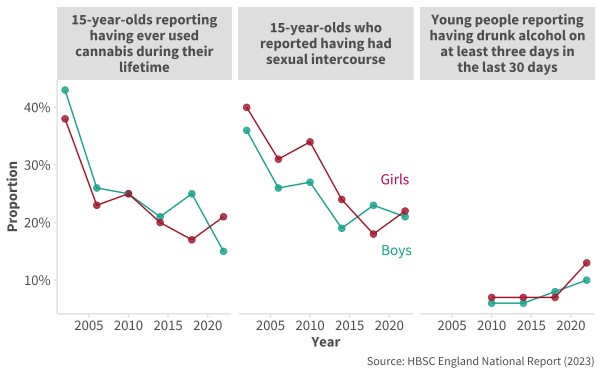

- Girls are now more likely to engage in ‘risk-taking behaviours’: Following long-term stability (or declines) in young people’s risk-taking behaviours, rates have recently increased amongst girls (overtaking boys in 2022, having been below in 2018) based on cannabis use by age 15, having had sex by age 15 and regular alcohol use.

Figure 1: Gender differences in reported risk-taking behaviour

The second area is social media:

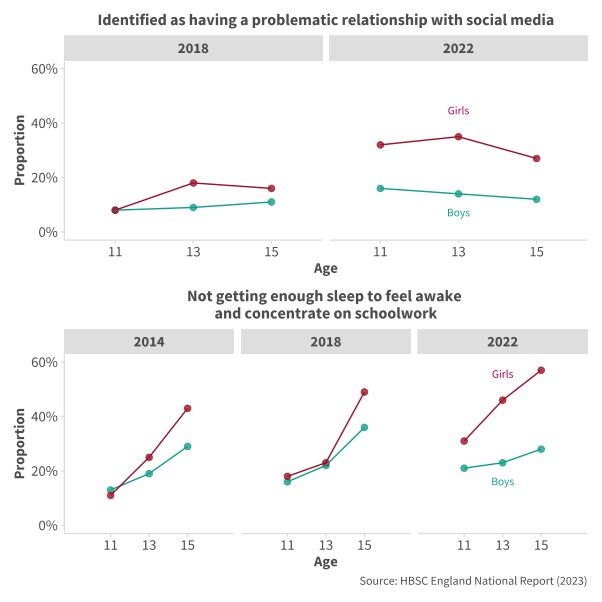

- Girls are more likely to report ‘problematic social media use’, and this is a growing problem: There is a stark (and growing) gender gap in the proportion of 15-year-olds reporting problematic social media use – in 2022, this rose to 27 per cent among girls (from 16 per cent in 2018) but was little changed among boys at 12 per cent (from 11 per cent in 2018).

- More than half of girls report not getting enough sleep: Perhaps related to problematic use of social media, there is a marked (and growing) gender gap in the proportion of 15-year-olds reporting not getting enough sleep to feel awake and concentrate on schoolwork. In 2022, this rose to a shocking 57 per cent of girls (from 49 per cent in 2018) and fell to 28 per cent among boys (from 36 per cent in 2018).

Figure 2: Gender differences in the proportion of young people identified as having problematic social media use and reporting insufficient sleep

The third area is safety and belonging:

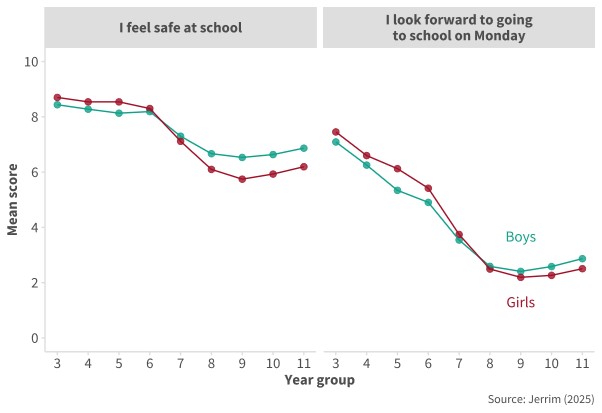

- Girls feel less safe in school compared to 2019: A raft of recent research shows that girls’ sense of safety in school has declined considerably since the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2023, girls’ sense of safety in school in England fell by 22 per cent — more than double the 10 per cent drop among boys, and one of the steepest declines internationally.

- Girls’ sense of safety reduces as they get older: As girls move through secondary schools, their sense of safety falls sharply below that of boys (having been above during primary school) and stays that way for the remainder of secondary school.

- Girls are also more likely to express worry than boys: Similarly, having been aligned during primary school, by year 8 girls are profoundly more likely to express worry about school than boys, including worries about going in the next day and returning to school after the holidays.

- Girls are also less likely to feel a sense of belonging in school: Compared with boys, girls are less likely to feel a sense of belonging in schools .Girls are also less trusting of both teachers and peers than boys, and less likely to feel that teachers ‘care about me as a person’.

Figure 3: Gender differences in reported sense of safety and worry

We don’t know why girls are now performing worse on a range of measures compared both with previous years and, in some cases, with boys.

But one experience seems particularly relevant to explore given the current national conversation: the issue of violence against women and girls (VAWG).

VAWG is any harm directed toward a girl or woman because of their gender. It lies on a spectrum, with behaviours ranging from harassment and intimidation to acts including sexual assault and exploitation.

Violence against women and girls and their worsening wellbeing

The few prevalence studies which exist show that sexual harassment and certain kinds of violence are common experiences for girls; in education settings these experiences are often dismissed or made invisible by their normalisation:

- A 2009 survey found that one in three girls, compared with one in six boys, experienced sexual violence or coercion by a partner.

- Another 2014 survey found that three in five girls and young women aged 13 to 21 experienced sexual harassment at school or college.

- Another from 2017 found that a quarter of girls experienced unwanted physical touching of a sexual nature at school.

The Women and Equalities Committee highlighted the prevalence data in a 2016 inquiry and concluded that sexual harassment and abuse of girls is accepted as part of daily life in schools and colleges.

These studies, spanning the last decade plus, show these experiences are not new — but the rise of digital technologies and social media over this period has opened up new avenues for abuse.

For example, many young people are in constant unsupervised communication with peers and pictures are taken and shared more easily. And there is growing concern in the UK and US about online misogynistic content — backed up by some worrying survey findings on how its consumption is playing out in schools.

In 2021, Ofsted published a review off the back of the Everyone’s Invited campaign, an online collection of testimonies from young people from close to 3,000 schools in the UK and Ireland which highlighted experiences of sexual harassment, coercion and assault in or around school. The review found that virtually all girls interviewed had been sent explicit pictures or videos they did not want to see, compared with half of boys, and experienced sexist name-calling, compared with three quarter of boys. Authors concluded that these issues were so widespread that all schools and colleges should act as though sexual harassment and online sexual abuse are happening even in the absence of specific reports.

The Department for Education responded by publishing updated guidance for schools and colleges on how to identify, minimise risk and respond to instances of sexual harassment or violence, which was later merged with broader statutory safeguarding guidance.

Young people who experience gender-based violence may go on to struggle with depression, anxiety, eating disorders, substance misuse, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Given the high likelihood that many girls will experience some form of gender-based violence during adolescence coupled with the recent rise of online misogyny, we urgently need more research exploring how these factors may be driving the worsening mental health and wellbeing of girls. From surveys of young people and diagnostic prevalence data, we know that the gender gap in mental health emerges in early adolescence – at the same age when experiences of violence against women and girls in school and online likely become more common.

What next?

This blog lays out findings related to girls’ and young women’s wellbeing – on worsening mental health and related outcomes, and the high prevalence of VAWG. We find that across multiple indicators spanning mental health, social media use, and school safety and belonging, girls are faring worse than boys, and increasingly so, post-pandemic. It appears that narrowing attainment gaps may be symptomatic of the widening wellbeing gaps, but the reality is that robust research into how these factors interrelate does not yet exist.

It’s important to note that the education and longer-term outcomes of boys and girls still paint a complex picture. While the attainment gender gap may be closing (and in the case of maths and science, going into reverse), girls are still performing better than boys, on average. Yet, despite this, men continue to earn more than women particularly after early adulthood and the ‘motherhood penalty’.

Taken together, existing research suggests that gender remains one of the most important factors for experiences and outcomes in education. More research is needed, addressing questions such as: do experiences of gender-based violence in schools and online play a role in girls’ worsening mental health? Does exposure to online misogynistic content contribute to these experiences? And is there a pathway through which these potentially related factors are contributing to lower levels of belonging and safety, and worse attainment, for girls at school?

We need a much stronger focus on pupil wellbeing, not just attainment outcomes, and, as a first step, to consider collecting this data centrally building on the work of the #BeeWell programme. How do we ensure all young people, regardless of gender, feel safe, respected and valued at school? How do we make education a place where they want to be and succeed? These are the urgent policy questions we must address.

[1] This is after controlling for other pupil, school and region characteristics.