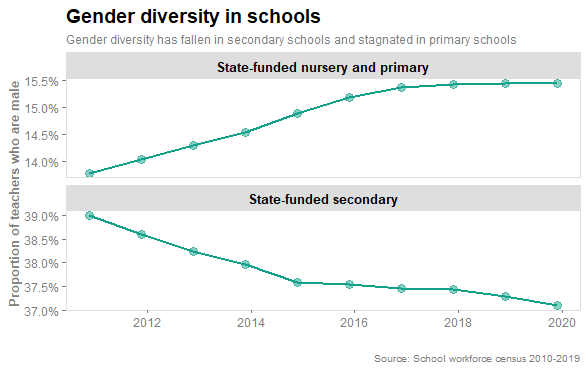

Teaching is a female dominated occupation across the OECD. While men have, historically, been overrepresented in senior positions, the school workforce in England is no different. The latest data shows that the school workforce is becoming even more female dominated. The proportion of men in secondary schools has fallen year on year since 2010 (to 37.1 per cent) and has stagnated in primary schools over the last five years (to 15.4 per cent).

The decline in the proportion of men in the school workforce has occurred across most of the country. Since 2010, every region in England has seen a decline apart from Inner London.

This decline is likely to be caused by the public sector pay freeze as evidence from the UK shows that men’s decision to go into teaching tends to be more responsive to wages than females. Since 2010 teachers’ wages have largely stagnated and, despite the recent uptick, fallen in real terms by 9.7 per cent.

While the Covid-19 induced surge in applications for teacher training programmes has increased the number of male applicants since March, up 2,660 (37 per cent) compared to the same period last year, this boost in unlikely to have a significant effect on the gender diversity of entrants as an additional 4,700 female applicants (up 36 per cent) have also applied.

Furthermore, male applicants have disproportionately applied to teaching later in the round (40 per cent of applicants in September and August were male compared to 28 per cent in November and December) so they are less likely to find a place as many positions have already being filled. Indeed, the proportion of male graduates who have been successfully placed on a training programme is almost identical to previous years despite a slight uptick in the proportion of applicants.

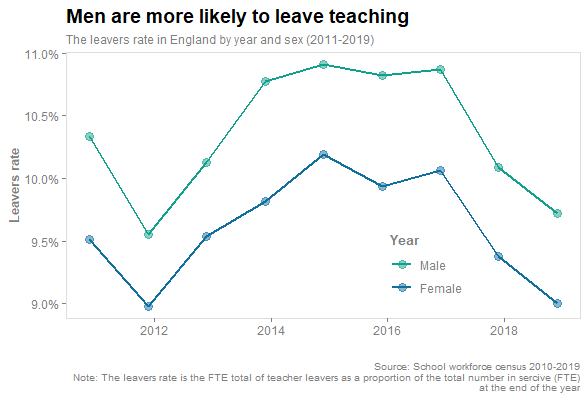

Men are also more likely to leave the profession. In recent years 10.6 per cent of male teachers have quit each year, compared to 9.8 per cent of female teachers.

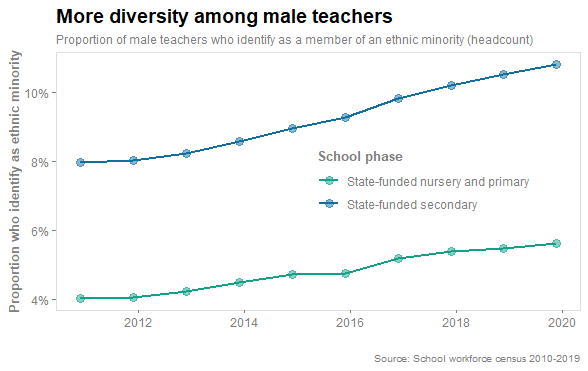

The good news is that there has been an increase in the proportion of male teacher from BME backgrounds. Since 2010 the proportion of male teachers from a BME background has increased in both primary schools (by 1.6 percentage points) and secondary schools (by 2.8 percentage points). Consequently, the proportion of men in the school workforce from a BME background in 2019 (9.1 per cent) is gradually becoming more representative of the population (14 per cent) although there is still some way to go. Evidence from the US found that students who had “a teacher like me” (sharing the same race, ethnicity and/or gender) typically achieved higher learning outcomes.

This does mean that the fall in the number of male teachers has been driven by white males. Indeed, the number of white male secondary school teachers has fallen by over 12,800 since 2010, a fall of 17 per cent. This is an important consideration in areas where there is a prevalence of underperforming white working-class boys.

We also know that, despite the surge in applications, subject-specific shortages in physics and maths are likely to persist. In the short term if policymakers want to meet recruitment targets in subjects such as physics and maths, they are likely to need to recruit more men because the pool of potential subject specific teachers is predominantly male. For example, male graduates outnumber female graduates in physics 4 to 1 and maths 2 to 1.

In line with empirical evidence EPI has recommended that top up payments should continue be made to maths and physics teachers in the most disadvantaged areas to recruit and retain subject specialist teachers where they are most needed. Such payments are likely to attract both more men and women into teaching in shortage subjects. However, given that the pool of graduates for such subjects is predominantly male, it is important to understand the root cause of why more male graduates don’t choose teaching.

With all of this in mind policymakers should:

i) Not be complacent about the surge in teacher numbers. The Covid-19 boost is only likely to be short term and is unlikely to plug subject specific shortages.

ii) Ensure that there is gender and ethnic diversity at different levels of seniority as well as amongst different communities.

iii) Focus on the pipeline of teachers. While we do want to attract more men into the profession, we equally want more girls and women to study STEM subjects to address pay disparities, not just in teaching, but across the labour market in general.

Correction Notice:

There was an error in the figure ‘More diversity among male teachers’. The original figure included all groups that were not White (defined as White British, Any other white background, and White Irish) as BME. This incorrectly included those with missing information (information not yet obtained and refused) as BME.

This has been corrected and the figure updated. BME is now defined using the following groups: Black Caribbean, Black African, Any other black background, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese, Any other Asian background, White and black Caribbean, White and black African, White and Asian, Any other mixed background and Any other ethnic group.