The latest data from the university admissions body shows:

- A slight recovery in the number of EU student applications following their post-referendum dip;

- A significant fall in the number of students entering into physics and language degrees – at a time when schools face serious challenges recruiting qualified staff into these subjects;

- A further deterioration in the number of nursing applications following the removal of bursaries;

- A growing divide in applications between those in the poorest and those in the most affluent areas; and

- A further fall in the number of mature students.

Last year’s UCAS July application figures were awaited with much anxiety by the university sector. It was the first full application cycle after the EU referendum result, and after bursaries and support for nursing students were scrapped.

Our subsequent analysis concluded that those fears were well-founded: the number of applications from EU students went down by 5 per cent, while applications to nursing degrees fell by 23 per cent in England. The 8 per cent decline in black applicants was also concerning, especially considering that applicants from this ethnic group are more likely to be mature students, who have been particularly affected by recent reforms.

This year’s figures do not come after any major policy change, other than the increase in the repayment threshold for student loans. The government’s Post-18 Funding Review, which launched its call for evidence at an EPI conference in March, is still underway – with its outcomes uncertain.

This means that this year’s question is principally: have last year’s trends remained?

Overall, the number of applications to UK universities has fallen by 2 per cent. This is despite a 2 per cent increase in the number of EU applicants, after last year’s unprecedented drop. Non-EU applicants are up by a large proportion too: they have submitted 6 per cent more applications to UK universities than last year. The number of English applicants has gone down by 4 per cent, and 5 per cent in Northern Ireland.

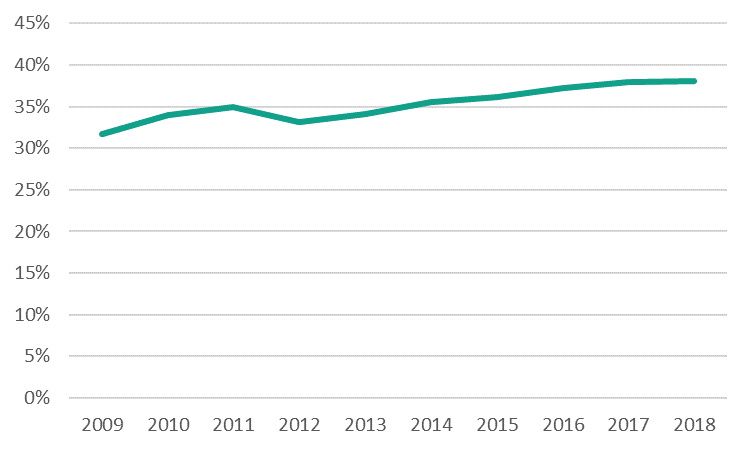

However, 18-year-old application rates (the proportion of that age group applying to university, out of all applicants) are at a record high, at around 38 per cent, with little change in the last year. The application rate is only higher in Northern Ireland: 48 per cent, although it has been decreasing for 3 years in a row. As usual, 18 year-olds in Scotland and Wales are less likely to apply: 33 per cent do so in Scotland (-0.2 pp) and 33 per cent in Wales (+0.2 pp).

Figure 1. Application rates among 18-year olds in England, 2009-2018

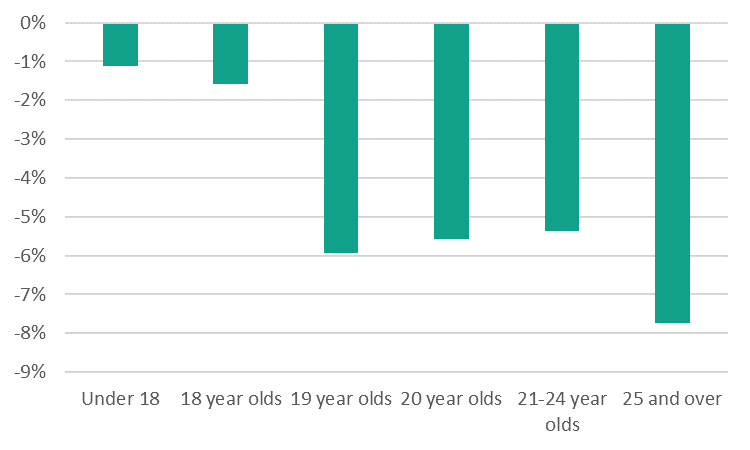

If the fall isn’t being driven by 18 year olds, where is it coming from?

The sharp decrease of mature applicants of previous years continues – and appears to be causing the decline. Applications from those aged 25 or older have fallen by 8 per cent. Between 2010 and 2018, the decrease was 34 per cent – that’s 23,600 fewer mature applicants.

Figure 2. Change in applications number by age groups, England, 2017-2018

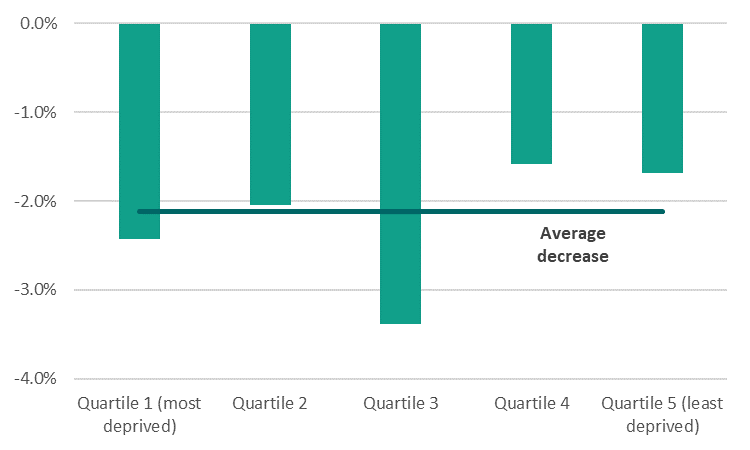

Today’s data also allows us to examine how higher education participation is represented in areas across the UK. The participation of local areas (POLAR) measure splits local areas into five groups (quintiles) based on the proportion of young people who enter into HE – acting as a proxy measure for levels of disadvantage.

This year’s July release shows that, while there are fewer applications across the board, this is represented unevenly in the different groups. The quintiles with highest participation rates see the smallest decreases: 1.7 per cent fewer applicants from the very top group (quintile 5) and 1.6 per cent less from second to top group (quintile 4). However, there are substantially fewer applications coming from the middle quintile (-3.4 per cent), followed by those from quintile 1 (-2.4 per cent) and quintile 2 (-2.0 per cent).

Figure 3. Change in applications number by POLAR areas, UK, 2017-2018

Significantly, this means that there is a growing divide between those at the bottom and at the top quintiles – in other words, a gap between the most and least well-off students.

In addition, the new release shows applications from black students in England are down by 4.6 per cent, while applications from white students have decreased by 5 per cent. Those from Asian, mixed and other ethnic groups have, on the other hand, seen a slight increase.

In terms of subject choice, nursing degrees also appear to be an important factor behind the fall. After grabbing headlines last year, this year the number of applicants has fallen again: English applicants are down by 12 per cent compared to last year – with a fall of 9 per cent across all UK nations.

Overall, this week’s figures mean that the number of applicants to nursing degrees in England has now declined by as much as a third since the bursaries were scrapped, and by 27 per cent in the UK overall (between 2016 and 2018).

Conversely, applications from UK students to medical degrees are up by 8.8 per cent – though subjects such as Physics or European Languages have seen significant falls, by 8.6 per cent and 10.6 per cent respectively. This will not be welcomed by schools, which a recent report from EPI found were struggling to recruit physics or modern languages’ teachers, among other subjects.

In summary, some of the trends of last year remain, mainly the fall in applications to nursing degrees. However, applications from EU students have recovered slightly, at a time when those from UK candidates are down – despite an all-time high in application rates, which keep their upward trend.

The widening gap between better and worse-off areas is also a worrying sign, as is the fact that some ethnic groups are seeing more severe decreases than others. The sustained decrease in applications from mature students will also continue to draw concern – and should prompt the Post-18 Funding Review into urgently considering alternatives to support older HE participants.