The approach to awarding GCSEs this summer has been like no other. This morning’s data from the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) shows that the move away from examinations to teacher assessed grades as a result of the pandemic has changed the profile of grades awarded considerably. This is a short summary of what we know about results so far. Note that results refer to entries in England for all ages unless otherwise stated.

Firstly, we should not expect things to look the same as a normal year

The process of teacher assessment, with limited controls, a lot of flexibility over what could be included as assessment evidence, and a process in which teachers are likely to give students the benefit of the doubt, meant that an increase in grades was inevitable.

Even in a perfectly moderated system, the issue of the benefit of the doubt, or what a pupil is capable of achieving, would likely lead to an increase in outcomes. Imagine two very similar students working at the borderline of a grade 3 and 4. In a normal year, we might expect one of them to fall just below the threshold in the exam – not quite the perfect question for them, not their best answer, distracted by something outside of the exam entirely. But the teacher, using professional judgement, cannot distinguish between them, and they both get the higher grade.

GCSE grades awarded are higher than last year and much higher than a ‘normal year’

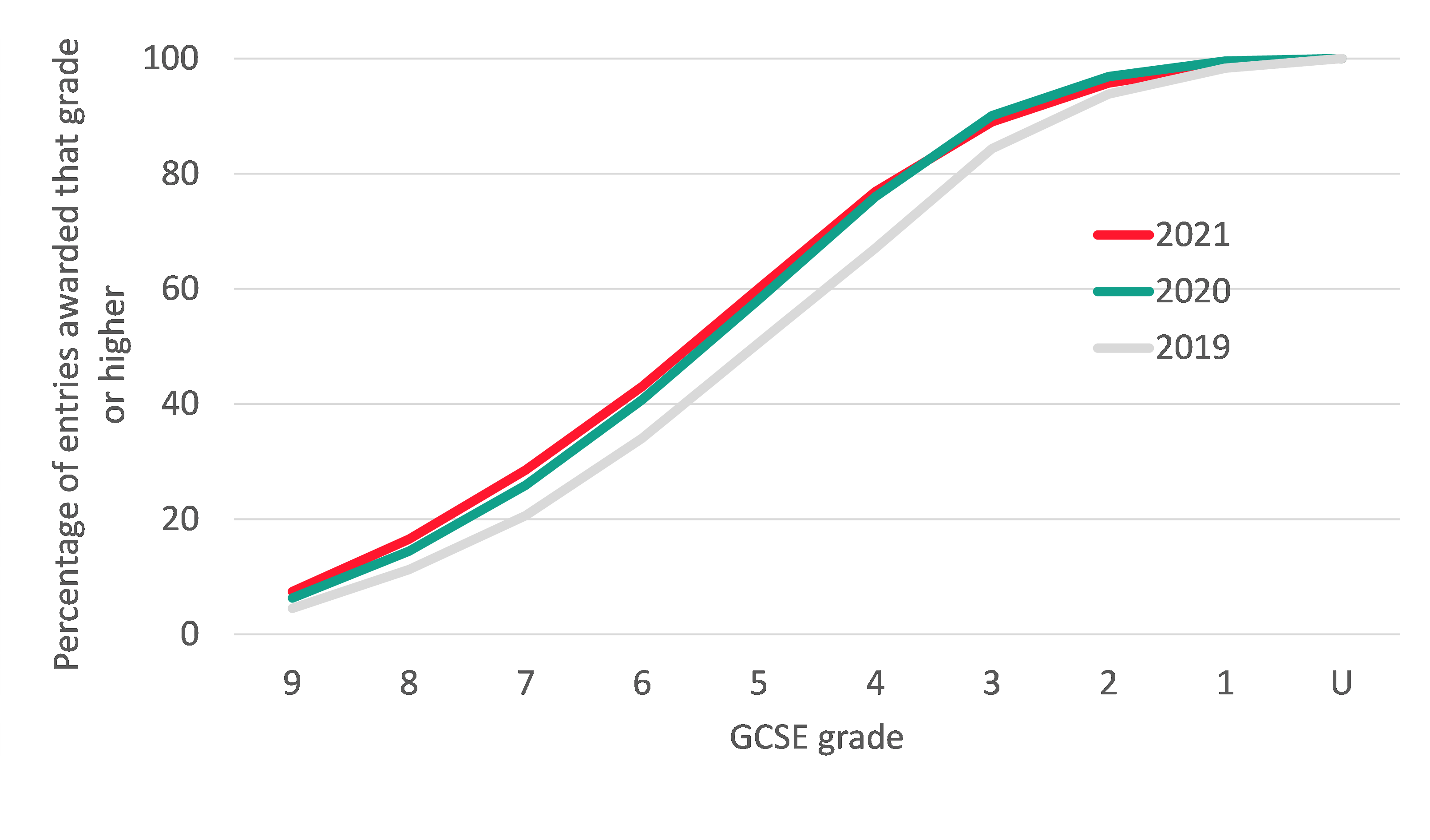

Last year we saw a noticeable shift in the attainment distribution (Figure 1). The proportion of entries that were awarded a grade 4 or above increased from 67 to 76 per cent, and the proportion achieving the top grades (7 to 9) also increased (by 5 percentage points, to 21 per cent). Overall, the shift was equivalent to an increase of around half a grade per entry.

That increase has been sustained this year but further increases have been relatively modest. 77 per cent of entries were awarded a grade 4 or above, an increase of 1 percentage point on last year and 10 percentage points on 2019. Overall, the average entry in 2021 was awarded a grade of 5.2 this year, up 0.6 grades overall on 2019 but only an increase of 0.1 on last year.

Figure 1: Cumulative grade distribution across all GCSE subjects, 2019 to 2021

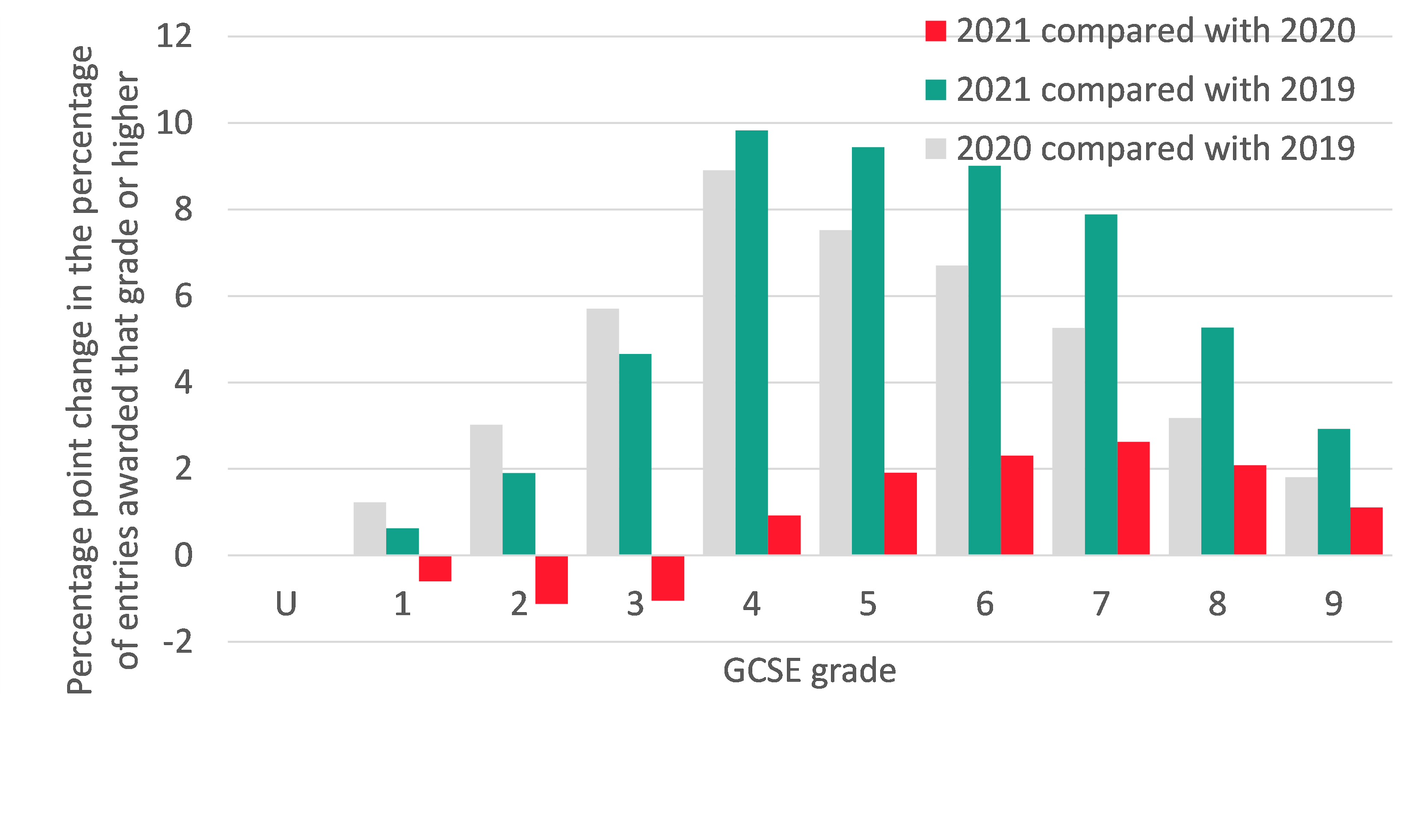

Last year, the largest increases were seen at the “standard pass” threshold. This year, higher grades saw the biggest increases (though increases were much smaller overall)

Since 2019, shifts in attainment have occurred across the grade distribution. Overall, it is at grade 4, (what the Department for Education would call a “standard pass”) that the effect is largest – possibly reflecting the importance of achieving this threshold in terms of future opportunities for students and an increased incentive to offer the benefit of the doubt to borderline cases. This is more easily seen in Figure 2 which shows how the proportion of entries achieving each threshold or above has changed this year in comparison with both 2019 and 2020.

But the increase at the grade 4 between 2020 and 2021 was relatively modest (1 percentage point), the largest increase was around the grade 7 or above threshold (up 2.6 percentage points).

Figure 2: Change in the percentage of entries achieving each grade or above across all GCSE subjects 2019 to 2021

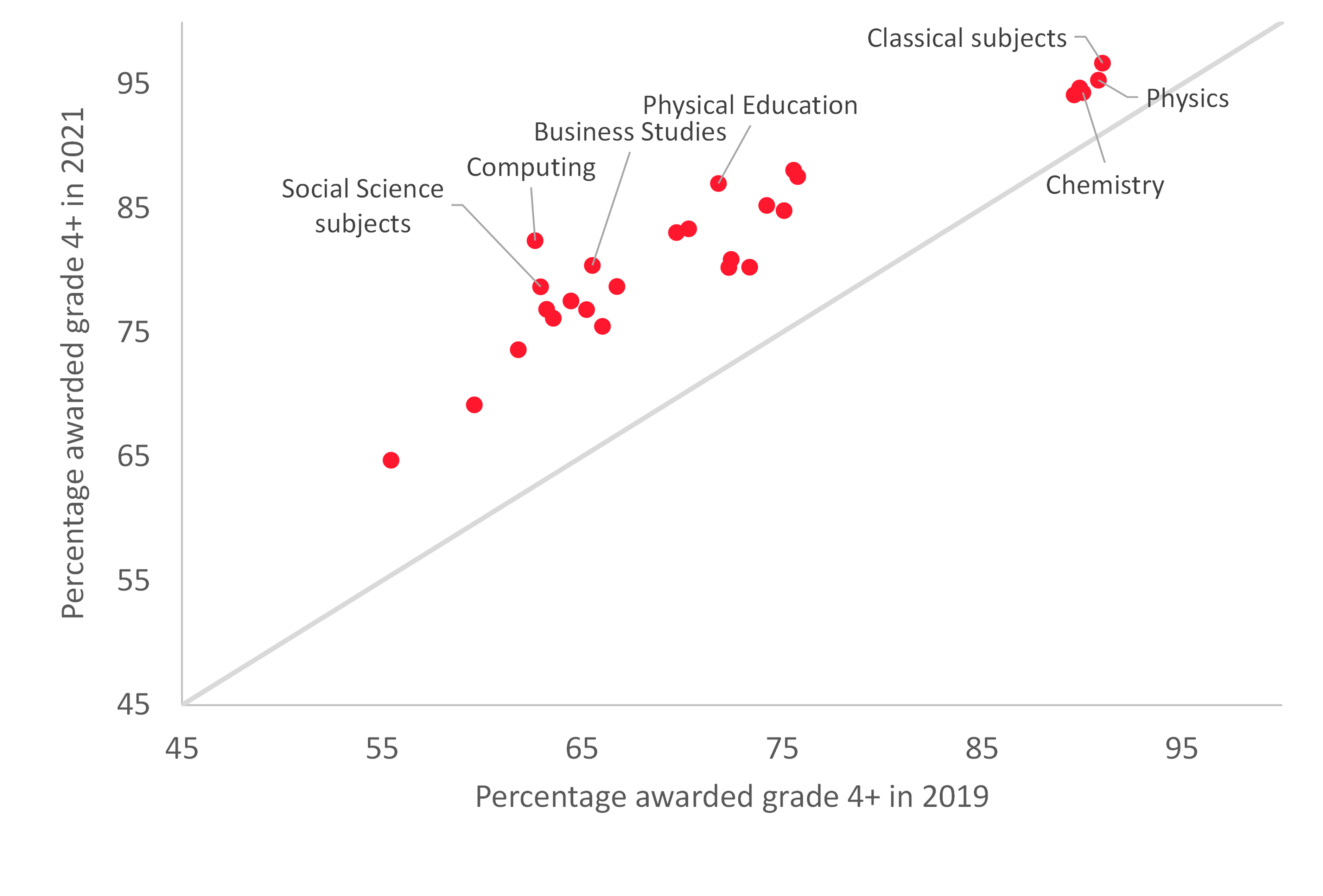

The increase in pupils achieving grade 4 or above is more pronounced in some subjects than others

The increase in awarded grades has been seen across all subjects, though it is more pronounced in some. Computing, social sciences, and physical education have all seen increases in the proportion of grade 4+ awards since 2019, of over 15 percentage points. Note that the increases in some subjects at this threshold were always likely to be smaller given existing high proportions of pupils achieving those thresholds – for example in classical subjects and the single sciences, the proportion of pupils achieving grade 4+ in 2019 was already around 90 per cent.

English and mathematics are the most important subjects for further study and employment. The increases in these subjects since 2019 have not been exceptional (though above average between 2020 and 2021). It still means that in 2021 an additional 85,000 entries in English, and 71,000 entries in mathematics have been awarded a grade 4 or above than would have been if grade patterns had followed those seen in 2019.

Figure 3: Percentage point change in the percentage achieving grade 4 or above between 2019 and 2021 by GCSE subject

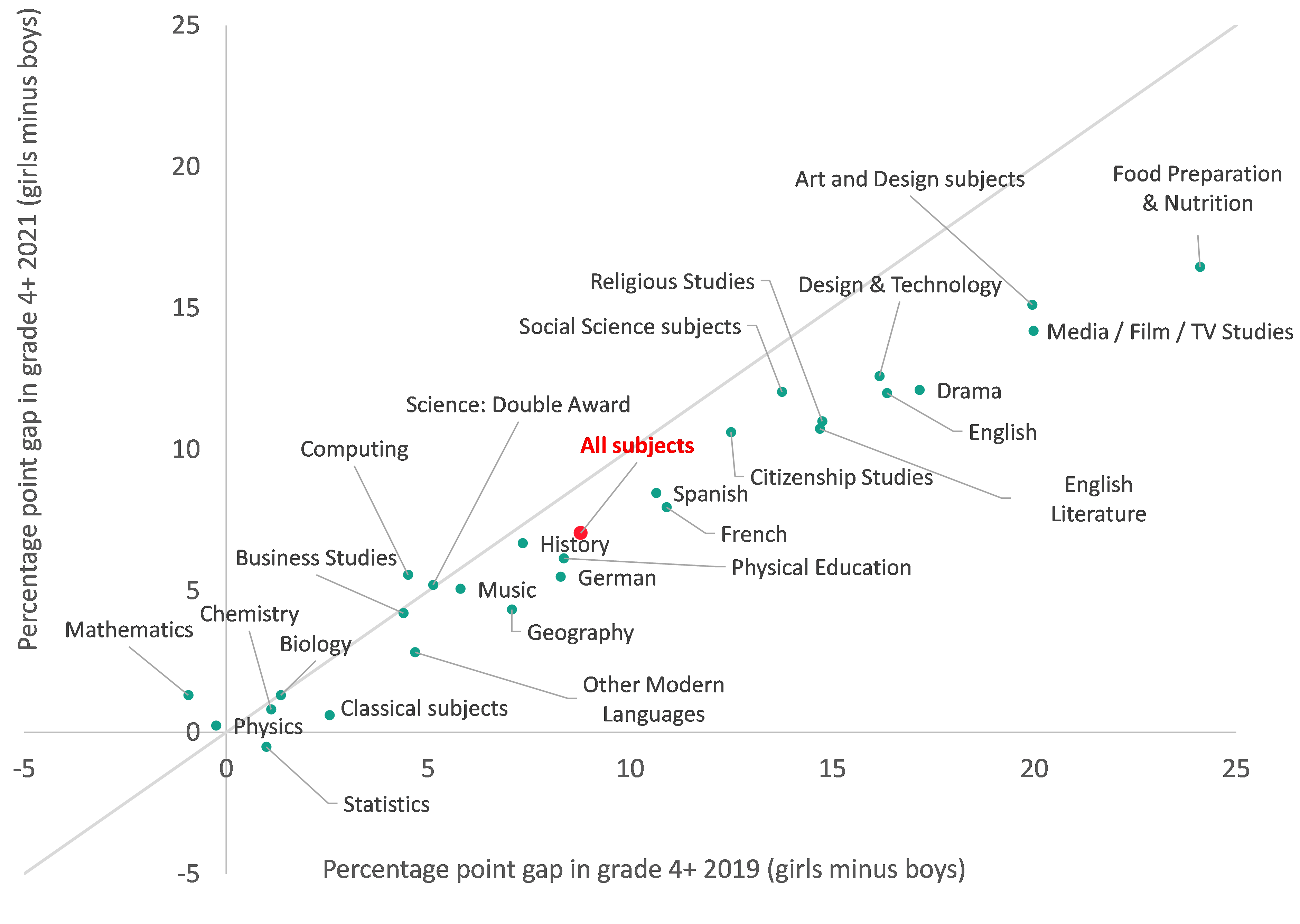

Outcomes for girls are higher than for boys, but slightly narrower than a ‘normal’ year

Last year also saw a reduction in the grade 4 attainment gap between girls and boys, though girls were still ahead by some margin. In 2020, 79.9 per cent of entries from girls achieved a grade 4 or above in comparison with 72.0 per cent of entries from boys – a 1 percentage point reduction in the gap between them. In 2021, 80.4 per cent of entries from girls achieved a grade 4 or above in comparison with 73.4 per cent of entries from boys – a further percentage point reduction in the gap between them. This is shown at subject level in Figure 4. Note that in subjects below the diagonal line the gap has narrowed since 2019.

The gap has widened at grade 7 or above, however. Just under a third of entries from girls (32.9 per cent) and just under a quarter of entries from boys (24.1 per cent) were awarded a grade 7 or above. This gap has increased by just under a percentage point since 2020.

Figure 4: Gap between attainment of grade 4 (girls minus boys) in 2019 and 2021

Conclusion

This analysis, like most of the discourse leading up to results day, has focused on the large increases in GCSE grades that we have seen for the two cohorts that have been most directly affected by the pandemic. For the reasons set out above, we should not be surprised that results look different from a ‘normal’ year, an increase of some kind was inevitable – though, with a more rigorous plan from central government and greater consistency in how schools were supposed to award grades, it is possible that some of that increase could have been mitigated.

But, of course, none of that should undermine the achievements of the young people receiving their grades today. The results represent great achievements in the face of such challenging circumstances. Ultimately, none of the people analysing and commenting on results today did their GCSEs in the middle of a global pandemic.

Policymakers now owe it to these young people to ensure that that the increased outcomes do not mask the challenges they have faced and may well continue to face as we (hopefully) exit the pandemic. We know from our own work that pupils have experienced learning loss over the last 15 months. Amongst Key Stage 2 pupils, learning losses in reading by the end of the spring term were typically of the order of two months, and higher still in mathematics. Further analysis of results earlier in the academic year show that it is pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds that have experienced the biggest losses with significant regional disparities too.

While the evidence for older pupils is limited it is a simple statement of fact that this year’s GCSE cohort have had a significant proportion of their courses disrupted by the pandemic. Next year’s GCSE cohort will not have had a normal school year since they were in year 8, we will have A level students for the next two years who have had their GCSE courses disrupted and who have not yet sat external examinations.

We now need to focus attention on education recovery for pupils, particularly the most disadvantaged and vulnerable – many of whom have been left behind by this pandemic. The government’s education recovery plan fails to meet the scale of the challenge of lost learning. Our research has shown that a three-year recovery package totalling £13.5bn will be required to reverse the damage seen to education from the pandemic – but the government has only committed a fraction of this to support pupils.

This year’s GCSE cohort and their teachers have worked hard to overcome the challenges that the pandemic has thrown up. It is time for them to be backed properly.