Two years of immense uncertainty for A level students finally ended today as they received their results. However, whilst individual students will, rightly, be focused on their next destination, today provides only a partial picture of what the pandemic has meant for this cohort as a whole. The fuller picture will only emerge from further analysis of results in the months to come. However, there are four important insights that we can begin to glean from the initial data on A level results:

There was a significant increase in grades in 2021

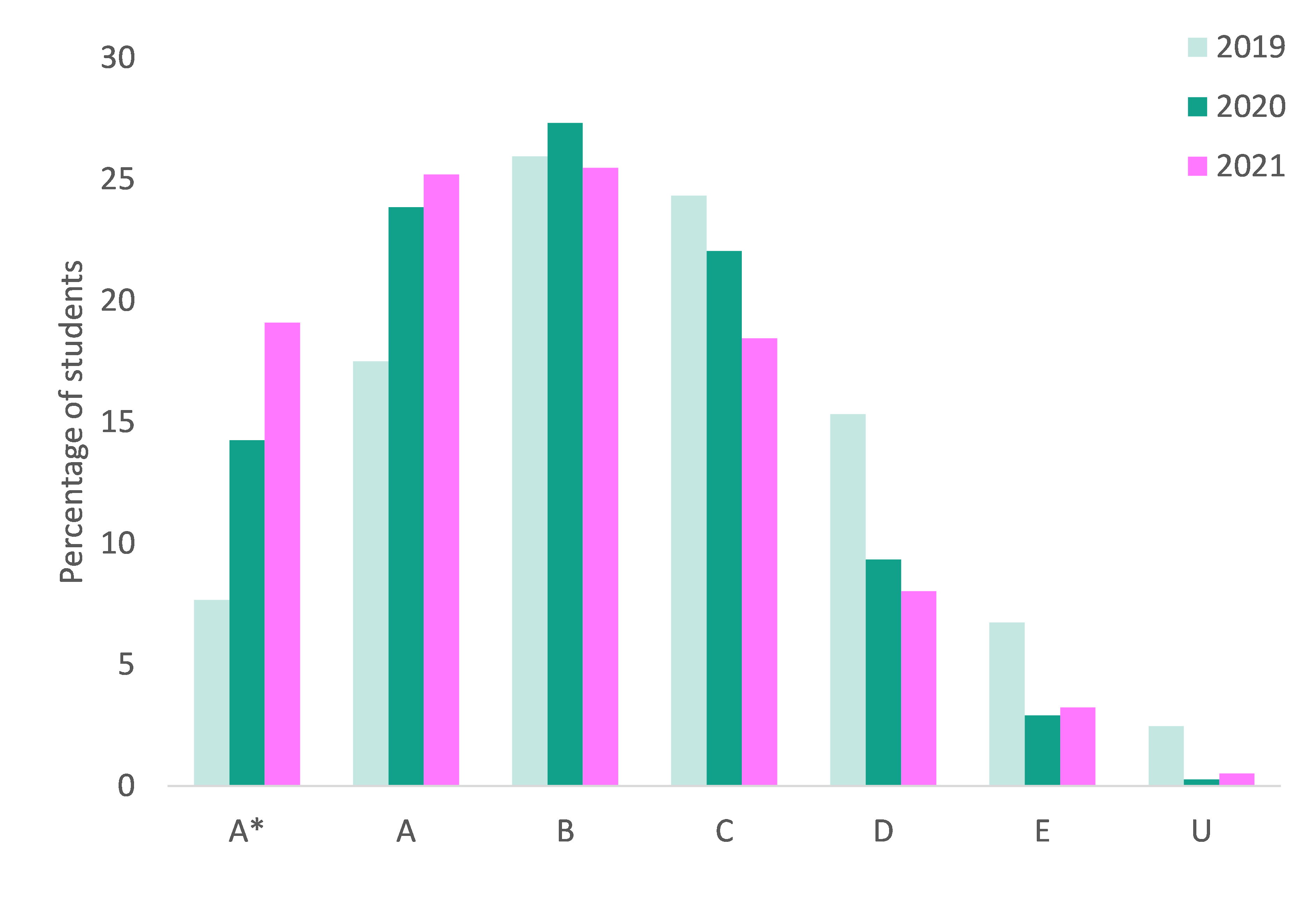

Figure 1: Distribution of grades, 2019 – 2021

44 per cent of A level grades were at A or A*, compared with 38 per cent in 2020, and 25 per cent in 2019. Since 2019 an additional fifth of students are now achieving the top grades. Given the amount of lost learning that took place over the last two years this may come as a surprise, especially as last year’s exams were also disrupted, with students receiving teacher assessed grades as a result. However, last year teachers were not expecting their assessments to become the final grade awarded to students. It was only after the government’s U-turn on the use of an algorithm that the (already made) teacher assessed grades came back into play.

Following last years’ experience, this year teachers were aware that their grades would be final at the point at which they made them. It’s likely that this year’s approach and context exerted an upward pressure on grades. We cannot know at this stage how much of this upward pressure was due to teachers giving students at grade boundaries the benefit of the doubt, teachers having a more holistic understanding of students’ abilities (especially those who might have otherwise had a bad exam day), or other external pressures to increase grades, such as parental pressure. The scale of the increases may suggest that a combination of factors played a role.

Given the same teachers will have made both the students’ predicted grades for university admissions and their final awarded grade, there may be fewer unpleasant surprises for young people today, as students are more likely to be awarded the results they were predicted. UCAS application data suggests that there has been strong demand for higher education places again this year. In general, it is largely expected that the higher education sector will meet this demand with a sufficient supply of places.

However, students who didn’t get the grades they expected may face additional challenges this year. The high demand in combination with many students achieving their predicted grades means that students applying through clearing may find the process especially competitive this year. Furthermore, some universities may struggle to deliver on all the places they offered for some of their more competitive courses. Indeed, we recently saw potential medicine students at Exeter offered £10,000 to defer their place for another year, whilst the government recently decided to relax number controls for medicine and dentistry courses.

Finally, different groups may be more or less successful when applying for more competitive courses. For example, we know that higher attaining disadvantaged students are particularly likely to be under-predicted compared with the grades they receive based on exams (Murphy and Wyness 2020). Given the use of teacher assessed grades this year, we may see similar patterns in final awarded grades. As disadvantaged students also lost the most learning on average, this group may well be particularly hard hit this year.

At the other end of the scale are students in independent schools. Whilst the proportion of top grades in all schools increased by 6 percentage points (from 38 to 44 per cent), in independent schools it increased by 9 percentage points (from 61 to 70 per cent). Grades for these students have historically been over-predicted on average and the nature of private schools means their teachers are more directly accountable to parents, increasing the risk of pressure to increase grades. However, these students have typically had higher grades than average and are likely to have experienced less learning loss. At this stage we cannot point to a single factor as being behind the increases for private schools.

Though the impact of the pandemic appears to be easing in the UK, a resurgence is a possibility. The government must move quickly to ensure exams for next year’s A level students are minimally disrupted. Unlike A level students taking exams in 2020 and 2021 these students’ GCSE’s were also disrupted, in 2019. As a result, these students may never have sat an externally set exam, and their GCSE results will have also been based on teacher assessed grades. Rather than waiting until the spring, as is currently planned, the government must confirm final arrangements for next year’s exams immediately to enable students, schools and colleges. To plan accordingly they need the certainty that has been in such short supply in recent years.

Girls now attain higher grades even in subjects more popular with boys

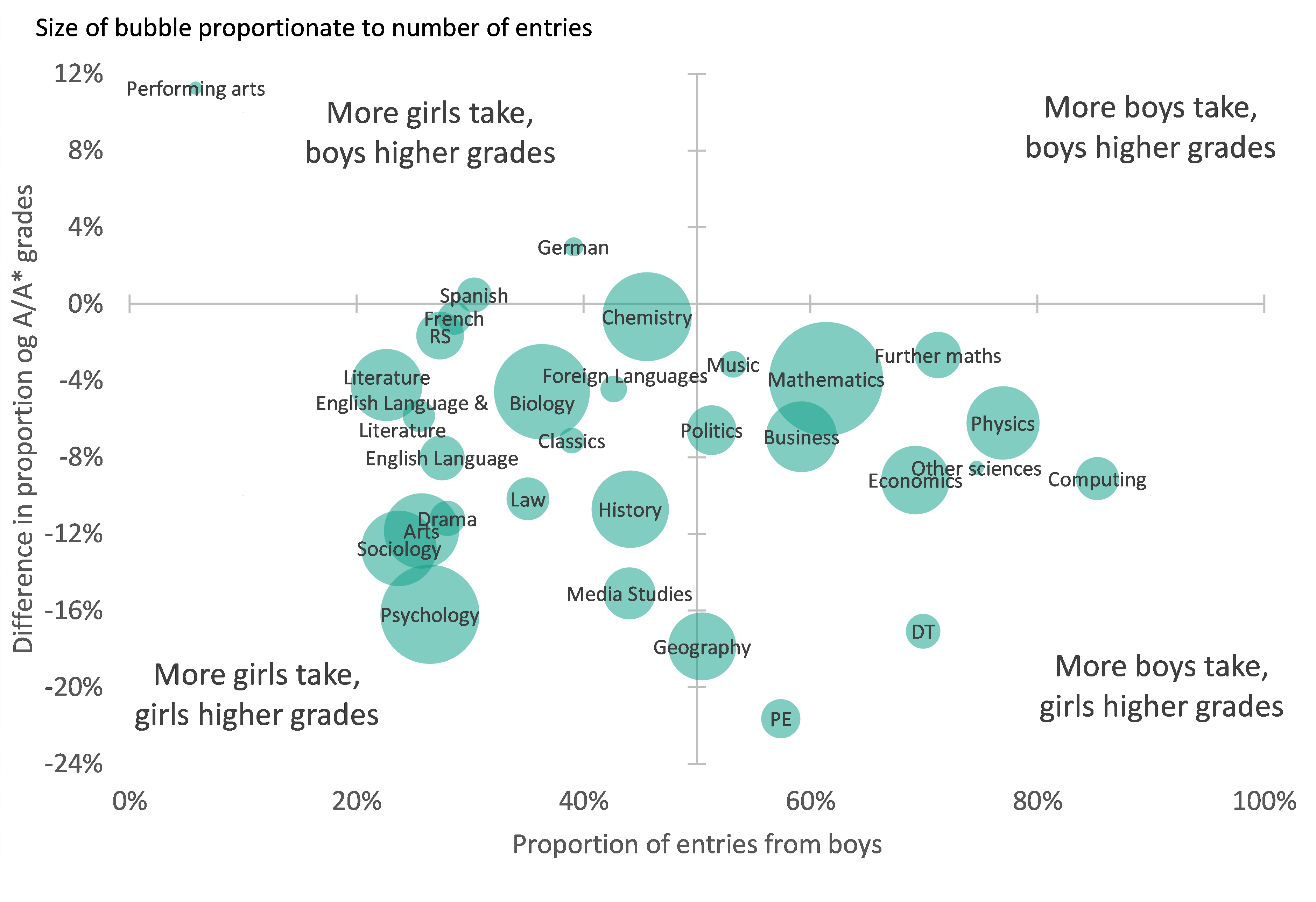

Figure 2: The A level gender gap: attainment and entries in 2021

Figure 2 shows that the subjects most commonly entered by male students aren’t necessarily the ones where they achieve higher average grades, and vice versa. The top left and bottom right quadrants of the chart show the subject areas where this is the case. In 2021, it was the case that female students were more likely to achieve an A* or A grade than male students in almost all subject areas.

The way qualifications have been awarded in 2020 and 2021, goes some way to explaining why the discrepancy between male students’ entry patterns and their grades is more pronounced than in a regular year. In recent years, final A level grades have been almost entirely determined by the exams students sit at the end of their course. Existing research suggests that, relative to coursework, final exams favour male students. The use of teacher assessed grades in 2020 and 2021 may then favour female students, relative to earlier years. The effect of this can be seen when considering changes in grades by gender and subject between 2019 and 2021.

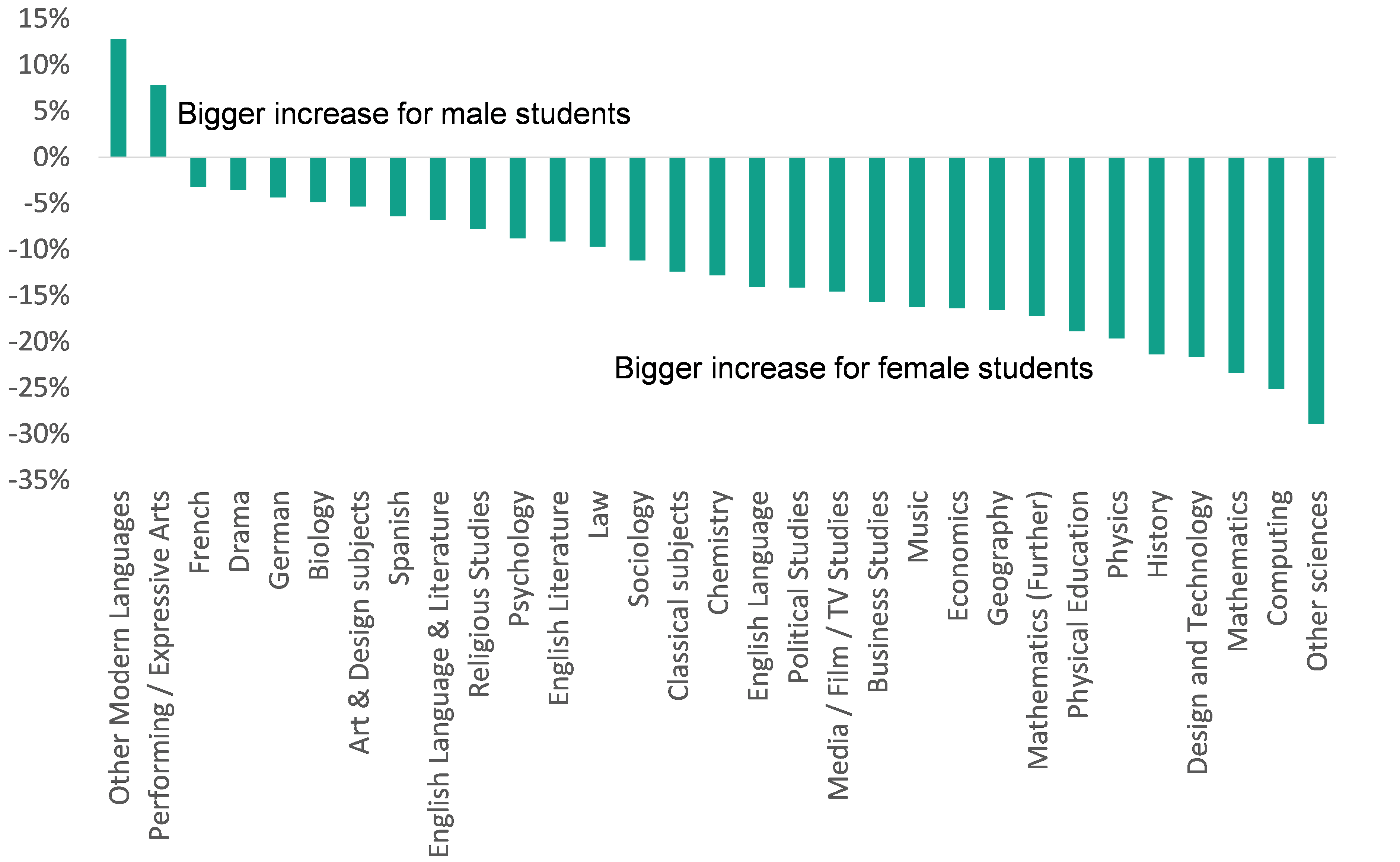

Figure 3: The difference in male vs female average grade increases between 2019 and 2021 by subject, measured as the percentage of a grade

Figure 3 shows that other modern languages and performing/expressive arts, were the only A level subjects where average grade increases since 2019 were greater for males than for females. Conversely, in all other subject areas, grades increased by a greater amount for females since 2019. This is particularly true in A level subjects with a high proportion of male entrants such as mathematics and computing. In these subject areas, average A level results rose by a around a quarter of a grade more for females than males since 2019.

Relative to a normal year, higher A level grades in these subjects may mean that female students are more able to access higher education courses in more selective courses with predominantly male applicants, though it is anticipated that the overall number of students studying in university will rise too.

AS level entries have fallen by three-quarters since 2018

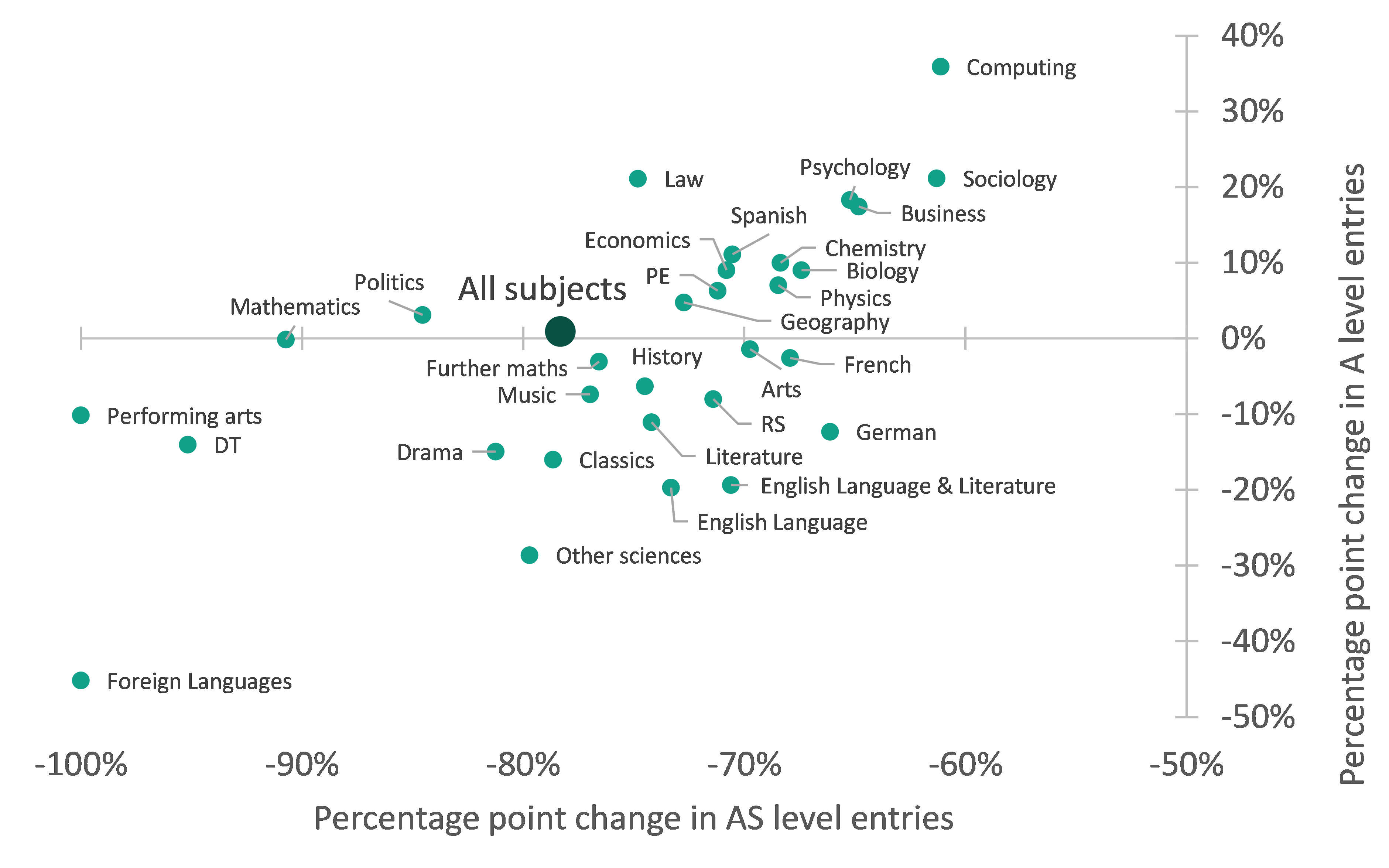

Figure 4: 2018 to 2021 change in A level and AS level entries, by subject

Having already fallen by 73 per cent between 2018 and 2020 the number of AS level entries fell to 78 per cent below 2018 levels in 2021. A level entries increased by 1 per cent between 2018 and 2021. The most notable falls in 2021 were in Design and Technology and Mathematics AS levels. The number of Mathematics entries fell from 71,463 entries in 2018 to just 6,626 entries in 2021. The fall in the number of students taking AS level maths is all the more surprising given the introduction of financial incentives for institutions to increase uptake.

Up until 2018 the main cause of the fall in AS level entries was likely to be the introduction of the decoupling policy, whereby reformed AS levels no longer count towards a full A level. However, this reform was largely bedded-in by 2019.

There have also been reductions in real-term funding per student for the 16-19 phase in recent years. Between 2012 and 2019 funding per 16-18-year-old student fell by 16 per cent (Britton, Farquharson, and Sibieta 2019). These funding pressures may also have played a part in the continued reduction in AS level entries, with more and more students taking three A levels, rather than three A levels and one AS level.

There is an increasing gap between grading for A levels and vocational qualifications

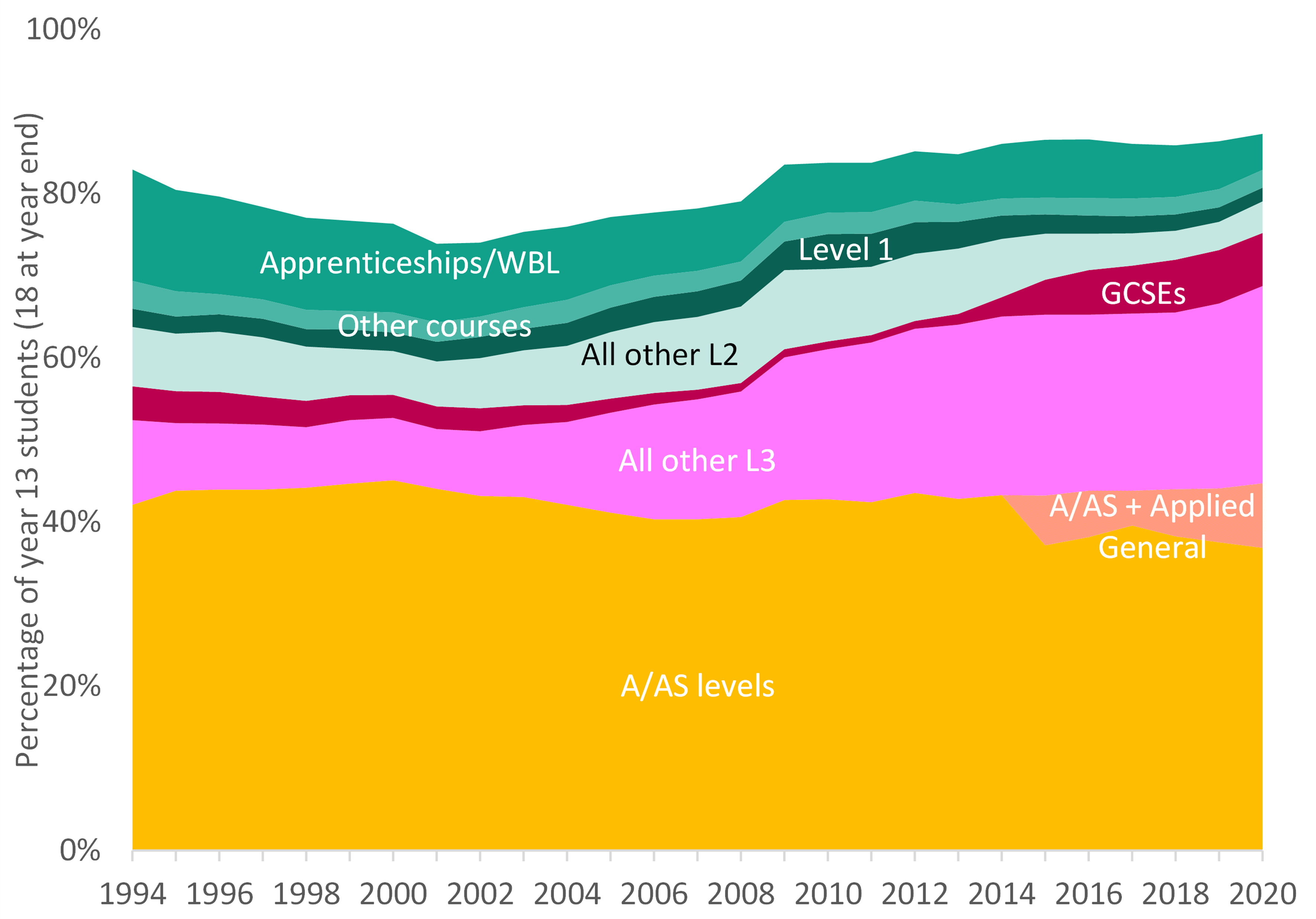

Figure 5: Participation of 18-year-olds by highest qualification aim

In 2020, results for these qualifications did not see the same increase as seen for A and AS levels. This is because, vocational qualifications were less affected by teacher assessments. Ongoing project work, interim and practical assessments for the majority of the course duration went ahead as usual, with only the last few months being interrupted. Although many final exams were cancelled, these other assessments meant there was less reliance on teacher assessment. EPI is currently investigating how the different approaches for A levels and vocational qualifications in 2020 contributed to differences in outcomes between students. We will publish this Nuffield Foundation funded research in early 2022.

In 2021 students taking vocational qualifications will have seen a far greater proportion of their study programme disrupted, experienced greater learning loss and have spent less time with the teachers responsible for setting their grades.

There are a range of vocational qualification types, and for the majority of these qualifications there were increases in the proportions of student achieving the top grades. However, for some of the most popular qualification type there were decreases in the proportion of student achieving the top grades.

There has been a significant increase in the proportion of students taking vocational qualifications at the same level as A levels (level 3). In 2002 over five times as many students took A levels compared with other level 3 qualifications, but by 2020 this had fallen to less than twice the number. These qualifications, Applied General qualification in particular, are increasingly used by students to apply for higher education places. Given A level students have seen much greater increases in grades in 2021, this may put students taking these qualifications at a disadvantaged when competing for places with students taking only A levels. As disadvantaged young people disproportionately enter these qualifications this disparity may also increase the gap in attainment between disadvantaged and more affluent students.

More broadly, we know from our research that many students, A level or otherwise, have experienced significant learning losses as a result of pandemic disruption. There is a real risk that grade inflation masks these losses. We now need to focus attention on education recovery for students, particularly the most disadvantaged and vulnerable many of whom continue to be left behind by this pandemic.