Every A-level results day is a major event in the life of the young people who have been anxiously awaiting their grades. However, the circumstances leading up to this year’s A levels results day are entirely unprecedented, and anxiety levels will have been especially high. Young people have largely been out of school or college since March, and many will have lost considerable learning and academic support during this time. And this is before we even begin to consider the wider impact of the pandemic on these young people, many of whom will have had missed contact with their friends, experienced disrupted home environments, and seen their parents’ jobs jeopardised. Some will sadly have lost family members to the pandemic.

In addition, the pandemic has also required the government to (temporarily at least) drop its emphasis on final exams. This year’s grades have been derived from a combination of teachers’ ranks of their students and an allocation of grades to the school predetermined by the GCSE grades of this year’s students and the A level grades of previous years’ students. In the absence of exams, this approach is designed to avoid the jump in grades that may have come from using the often overly generous teacher assessments alone. Evidence from the Netherlands, which saw a fivefold increase in schools graduating all of their pupils, and France, where the Baccalauréat pass rate increased from 78 per cent last year to 92 per cent this year, suggest that this risk was real. [1],[2]

However, as well as being overly optimistic in general, teacher assessment also tends to favour more advantaged young people over their more disadvantaged peers, even when their exam results would suggest otherwise. [3]This is also evidenced in the predicted grades for young people, which again tend to be higher for more advantaged students. [4] As this will affect the rankings given to students within a school or college, we might well expect to see some disadvantaged students losing out as a result. The qualifications regulator, Ofqual, suggest that this will not be the case, but given the evidence of bias in teacher assessment, this claim will require further scrutiny once the full results become available.

A last minute change to the appeals process has led to the creation of, what the government has referred to as a “triple lock”. In addition to the Ofqual moderated results and the ability of students to retake their qualifications in the autumn, there is now a third “lock”, the ability to appeal the decision made by Ofqual’s moderation using a result from a “valid” mock exam as evidence for the appeal. With mock exams varying significantly between schools in their style and purpose, the tricky job of validating these mock results will fall upon Ofqual, and if the likelihood or success-rate of these appeals varies between student groups, there remains a possibility of further increases to the attainment gap between different groups of students.

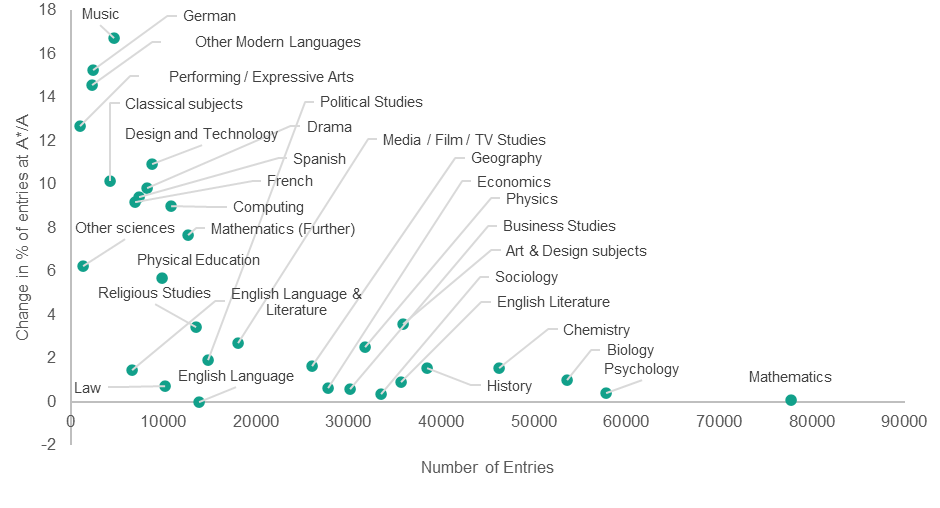

So how has all this translated into actual A level results this year? The good news for students is that the proportion of entries in England for pupil aged 18 achieving A*-A has increased by 2.4 per cent since 2019. The biggest improvements tended to be seen within subjects with a small number of students, with subjects such as German and Music seeing large increases in students achieving the top grades.

Figure 1: Number of Entries and Percentage Change in A/A* grades since 2019

This may be linked to lower levels of moderation of teacher predicted grades for centres with small numbers of entrants.

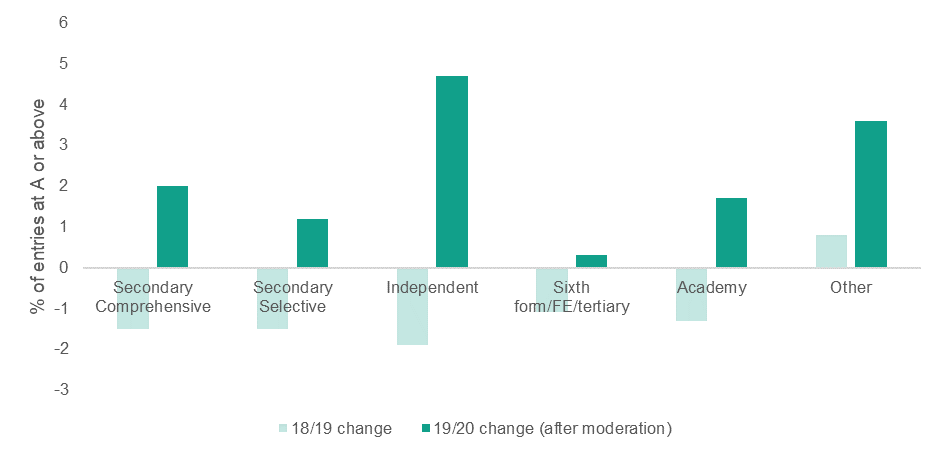

Between school types, however, there remain differences in the changes since last year. This may reflect different cohort sizes, historical achievement patterns within different centre types, and different approaches taken by centres towards estimated grades.

Figure 2: year-on-year changes at A or above grades

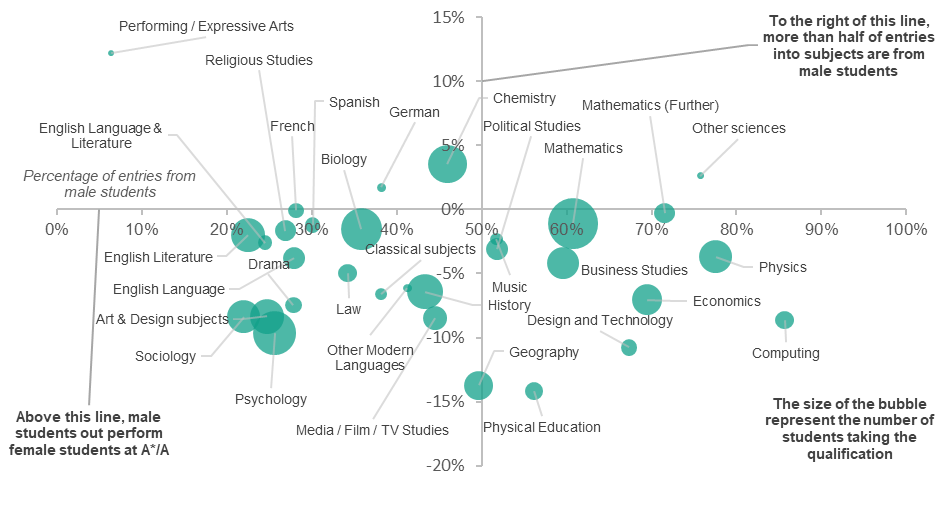

Maths remains by far the most popular subject, especially with male students, with 78 thousand entries among 18 year olds in England. Computing and business studies saw increases in entries of 13.2 per cent and 10.2 per cent respectively.

The over-representation of male and female students in different subjects remains, with male students making up 86 per cent of entries into computing and only 22 per cent of entries into English literature. For the first time in some years, a higher proportion of female students achieved A*/A grades in mathematics than male students, though the number of female student studying mathematics remains lower than men.

Figure 3: The A level gender gap: attainment and entries in 2020

And, for those that have both the inclination and the grades, continuing to university may be an even better option than usual. Despite the government’s plan to subsidise organisations to employ young people or take them on as apprentices, the jobs market looks likely to remain tough for young people for some time. And gap years will certainly be less appealing this year. So, even though the university experience itself may be changed by the pandemic, UCAS application rates for students are at a record high in 2020, with 40.5 per cent of all UK 18-year-olds applying.

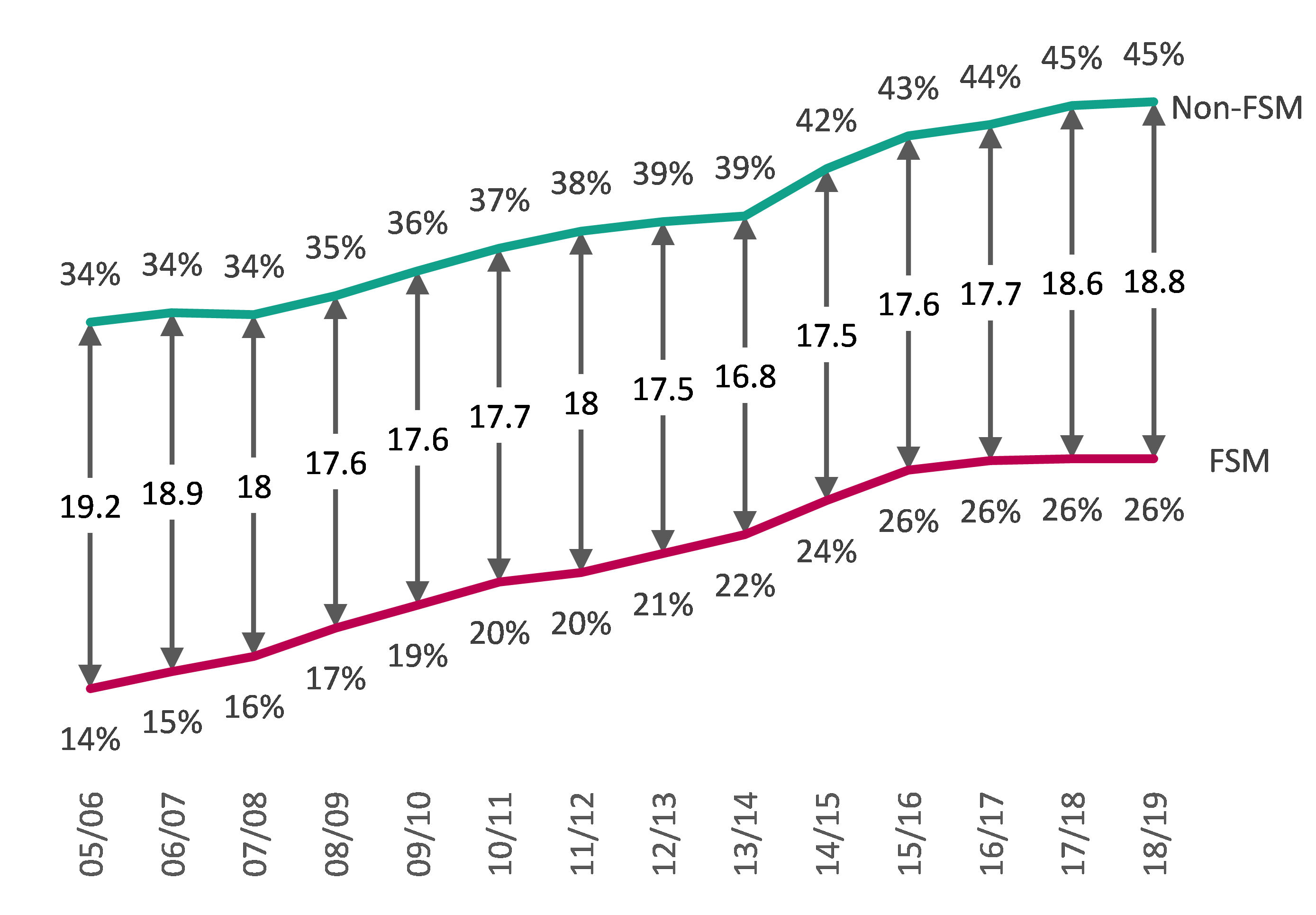

Figure 4: Percent of 15-year-old state-funded pupils who entered HE by age 19, by FSM status

It is, however, worth considering who may benefit. Higher education access for disadvantaged students flat-lined for the four years leading up to the pandemic, whilst entry for other young people continued to rise, leading to the largest access gap in twelve years. Looking forward to September, it is difficult to predict how the other impacts of, and responses to, Covid-19 will combine to grow or shrink this gap. For example, whilst the social side of attending university may not be what it was, will it still be more exciting for young people than their current alternatives? And how will potential students react to a more digital learning offer? How will this affect their views on the value of a £30k undergraduate degree? What will be the effect of the cap on universities’ recruitment of domestic students and the extra university places for engineering, bio-sciences, maths and healthcare courses? How might degree apprenticeships be affected given the impact of the pandemic on potential employers?

What matters here is not just the net impact on demand for higher education, but how this differs between disadvantaged and better off young people.

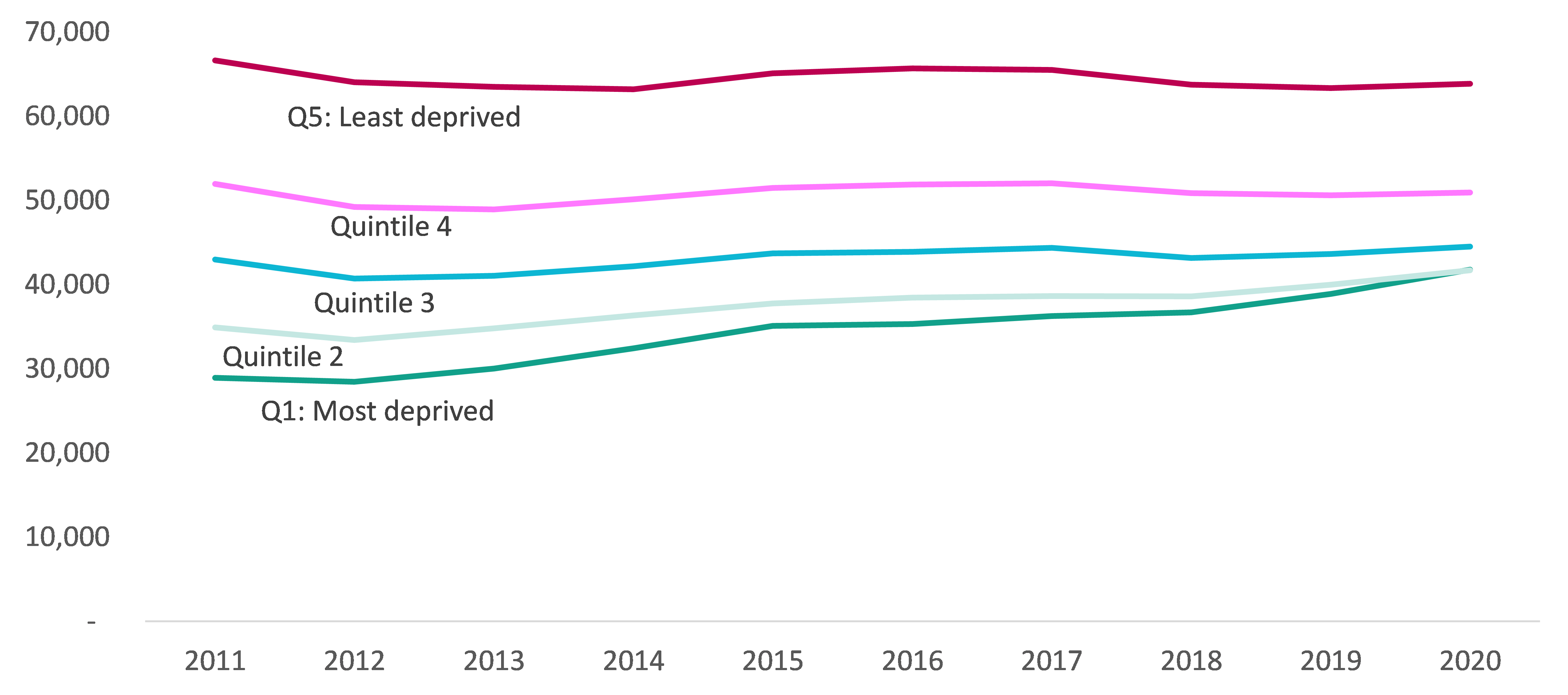

Figure 5: Number of UCAS applications from 18-year-olds, by Index of multiple deprivation: by June 2020

One glimmer of hope is that this year it is university applications from students from the most disadvantaged areas that have risen the most. As many of these applications were submitted before the impact of the pandemic became clear, we will need to wait to see how these applications translate into take-up. In the meantime the government must act on the main cause of this access gap: reversing the widening attainment gap observed throughout the schooling of disadvantaged young people that leads to them getting lower A level grades in the first place. That it is the very same young people who lost most learning during the pandemic only makes this ever-more pressing.

[1] The Times, ‘Coronavirus in France: Inflated Baccalauréat Results Are Test of Reforms’, The Times, accessed 4 August 2020, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/coronavirus-in-france-inflated-baccalaureat-results-are-test-of-reforms-t6tnj7d0d.

[2] ‘Scrapping of Final Exam Resulted in Significantly More High School Graduates: Report’, NL Times, 27 July 2020, https://nltimes.nl/2020/07/27/scrapping-final-exam-resulted-significantly-high-school-graduates-report.

[3] Simon Burgess and Ellen Greaves, ‘Test Scores, Subjective Assessment, and Stereotyping of Ethnic Minorities’, Journal of Labor Economics 31, no. 3 (July 2013): 535–76, https://doi.org/10.1086/669340; Tammy Campbell, ‘Stereotyped at Seven? Biases in Teacher Judgement of Pupils’ Ability and Attainment’, Journal of Social Policy 44, no. 3 (July 2015): 517–47, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279415000227.

[4] Dr Gill Wyness, ‘Predicted Grades: Accuracy and Impact’, 2016, 21.