Language learning in England: why curriculum reform will not reverse the decline or narrow the gaps

Across the education sector, stakeholders have emphasised the importance of learning modern foreign languages (MFL). In their research review series, Ofsted argued that learning a foreign language provides tangible benefits for pupils, by broadening their horizons and providing ‘knowledge and cultural capital’. The Department for Education (DfE) has defined language subjects, along with English, mathematics, the sciences and humanities, as ones that “[keep] young people’s options open for further study and future careers”. Others point to the potential benefits to the wider economy, with research conducted for the former Department for Business, Innovation and Skills finding deficient language skills to cost the UK economy 3.5 per cent of GDP a year, largely through its impact on limiting businesses’ potential exports.

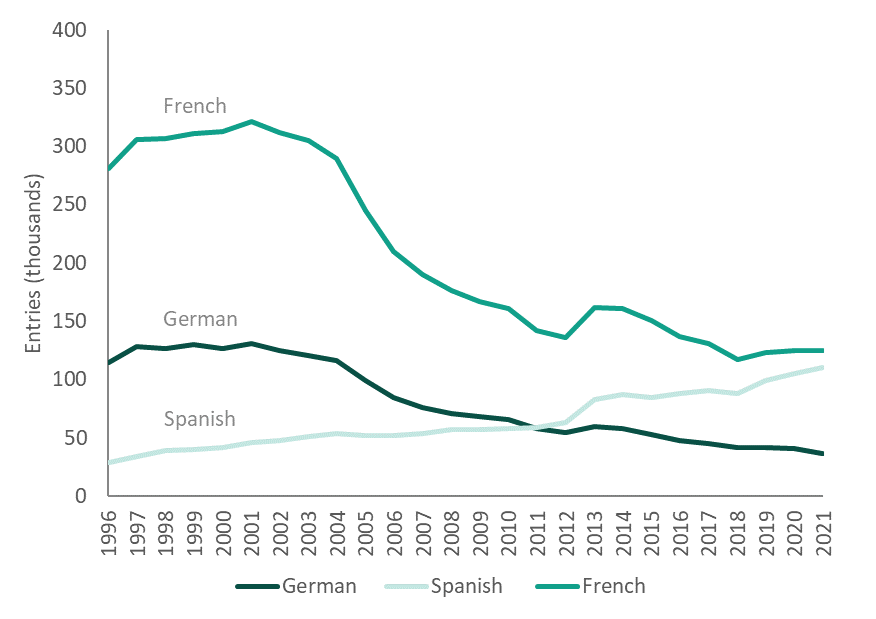

However, the number of pupils in England taking MFL has declined dramatically in the past 25 years. Figure 1 shows the number of pupils who entered GCSEs in Spanish, German and French, which together account for the vast majority (over 90 per cent) of all MFL entries. While there has been a steady increase in the number of pupils entering Spanish GCSE, the number of entries in German and French have more than halved from 1996 to 2021. This year’s GCSEs saw further declines in entries in French and German, but also in Spanish.

Figure 1. Number of pupils entering GCSEs in modern foreign languages, 1996-2021

Source: House of Commons briefing paper number 07388, and GOV.UK 2021 GCSE subject timeseries data.

Languages have not been compulsory at Key Stage 4 since 2004. Their place in the secondary curriculum was redefined in 2010 when MFL subjects were included in the English Baccalaureate (EBacc), which is made up of English language and literature, maths, double science, a humanities subject and a MFL. DfE set a target in 2017 that 75 per cent of pupils would study the EBacc subject combination at GCSE in 2022, rising to 90 per cent in 2025.

In spite of this target, language entries have continued to decline year on year since 2015, following a short incline immediately after the introduction of the EBacc. Currently, only about 40 per cent of pupils take all the required subjects of the EBacc, and although a large proportion (around 90 per cent) are taking four of the five EBacc subjects, in most cases the missing fifth subject is a MFL. Given the decline in MFL entries seen in this summer’s GCSE statistics, it is clear that the 2022 EBacc target has not been met.

Moreover, research from EPI and the British Council found that there are significant gender and disadvantage gaps in MFL GCSE uptake in England, which have failed to reduce in the past decade. The magnitude of the gender gap in particular is not seen in other EBacc subjects to nearly the same degree.

A matter of curriculum?

In light of the decline in uptake, DfE announced curriculum reforms to French, German and Spanish GCSEs earlier this year, with the aim of making these subjects ‘more accessible and attractive’. Students will begin studying these reformed GCSEs in September 2024, which will refocus assessed content towards 1,700 word ‘families’ (or 1,200 at foundation tier), at least 85 per cent of which will be statistically selected from the 2,000 most frequently occurring words in a given language’s conversation and writing.

The success of these reforms in improving languages’ uptake will depend on the extent to which sustained low entries are the result of the perceived difficulty of the curriculum content and on whether the reforms will change this perception. The success of the reforms in lowering the disadvantage and gender gap in GCSE uptake will depend on whether disadvantaged pupils and boys will be relatively more responsive to the reforms.

It is possible that the perceived curriculum difficulty has influenced the decline. The British Council reports that pupils often cite the perceived greater difficulty of language content when choosing not to take them at GCSE. Moreover, high prior attainment students in its Language Trends Survey were 26 percentage points more likely to take a language GCSE than middle prior attainment pupils.

It is also conceivable that plans to refocus GCSEs around commonly used vocabulary will succeed in counteracting the perception of a challenging curriculum. The government’s stated intention, to refocus on the vocabulary needed in practical conversation certainly aims to make languages feel more accessible and engaging. This may be particularly important to boost the uptake of disadvantaged students, as it might ensure that the curriculum is not based around activities which can be exclusionary for particular pupils, like foreign holidays or particular hobbies.

Alternative explanations for the decline and gaps in uptake

Even if perceived or genuine curriculum content difficulty played a role in both the decline in overall uptake and the presence of a disadvantage and gender gap in uptake, there are a number of other more intractable factors contributing to the decline in language study in England, which curriculum reform on its own will do little to shift.

First, the fact that MFL GCSEs have historically been scored more harshly than other subjects may have prevented pupils from taking them. Ofqual has revised the assessment for GCSE French and German in 2020, to prevent harsh grading from blocking students from achieving high grades.

Second, some factors leading to low uptake operate far before years 10 and 11, when languages are still compulsory. For example, although the provision of language learning is now statutory in primary schools, the lack of an implementation framework is leaving teachers with no clear guidance on how to teach MFL, which can hinder the quality of teaching. EPI’s report on the language gaps found that schools with wider Key Stage 3 language curriculums, more extra-curricular language activities, and senior management policies to guide pre-GCSE pupils towards languages, were more likely to have both higher language uptake and a narrower gender gap in uptake. The report also states that these kinds of senior management-led interventions are less prevalent in schools with more disadvantaged pupils.

Third, the current supply shortage of language teachers may prevent pupils from choosing MFL in their schools. EPI’s research on teacher shortages in England has shown that teacher exit rates are severe in shortage subjects, such as languages. In these subjects, around half of the teachers leave the profession after five years. The issue is particularly striking in disadvantaged areas, as many of these schools struggle to recruit teachers with relevant degrees. This is likely to worsen in the following years as a result of reductions in targets for MFL trainees, MFL bursary cuts and visa restrictions for EU nationals, who represent a large proportion of MFL trainees.

Fourth, positive attitudes towards MFL learning amongst students and parents have declined in response to the concept of ‘Global English’: the idea being that, because English is commonly spoken across the world even as a second language by non-native speakers, there is little value in native English speakers learning a foreign language.

Finally, the introduction of the Progress 8 measure of school performance. Unlike the EBacc, schools are able to perform well on Progress 8 even in the absence of a foreign language among its subjects. This has weakened the incentive for school leaders to encourage language uptake. A weak Progress 8 score has far more serious consequences for a school’s ability to attract pupils and staff than its EBacc score.

A more comprehensive approach

While it is possible that the curriculum reform in MFL will influence pupils’ perceptions about its difficulty, there is no clear evidence to date that it will have a substantial impact on uptake and on reducing the disadvantage and gender gap. Moreover, evidence highlights that both the decline in MFL GCSE entries and the gaps are likely to be driven by other factors besides curriculum.

If DfE is serious about improving language entries, a more comprehensive policy response should be considered, which might include supporting MFL provision from primary school to key stage 3, in particular for students that may have barriers to accessing and learning MFL, such as boys and disadvantaged pupils. Importantly, it is crucial to assess the impact of certain interventions, such as the Ofqual assessment revisions or targeted pay increases for teachers in shortage subjects, on uptake and inequalities, before deciding on any additional policy interventions.