Following the EU referendum result last week, the future of the UK economy is uncertain. While economists generally agree that leaving the EU could have short-term negative effects, there is disagreement over what it will mean for the economy in the long run. For example, while some believe that adopting the World Trade Organization’s rules will open up new trade opportunities for the UK[i], others argue that if Britain leaves the European single market, trade and productivity would fall[ii]. Moreover, according to a 2014 report by the UK Commission for Employment and Skills, if the new government decides to decrease the free movement of labour, it would “render vast retraining and up skilling efforts necessary. Skills retention would become more important; competition for limited talent would increase.”[iii] In thinking about the future of the economy, a key aspect to consider is how the UK’s current workforce stacks up against those of other countries and whether it possesses the skills to allow the UK to maintain its status as one of the world’s top economic powers.

A new report released yesterday by the OECD[iv] on its Survey of Adult Skills helps to shed some light on the state of the workforces around the world, including a portion of the UK workforce. The Survey of Adult Skills, which is administered by the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), tests the basic abilities of adults aged 16-65 in the areas of literacy, numeracy, and problem solving in technology-rich environments. In addition to assessing cognitive abilities, the Survey collects extensive background information in areas such as the individual’s level of education, earnings, and use of various skills – cognitive and non-cognitive – in the workplace and in the home. This latest publication builds on the organisation’s initial report on the Survey of Adult Skills[v], published in 2013, by combining the results from the 24 countries and regions that participated in the first round of the Survey with those from 9 new countries that participated in the Survey’s second round: Chile, Greece, Israel, Jakarta (Indonesia), Lithuania, New Zealand, Singapore, Slovenia, and Turkey.

Of the countries in the UK, England and Northern Ireland participated in the Survey of Adult Skills during its first round. The newly published report, which unlike the OECD’s first report at the Survey gives the results for England and Northern Ireland separately rather than combining the two, shows that England scored at the OECD average in numeracy and above average in literacy, ranking 21st and 14th respectively in those areas. Northern Ireland scored below average in numeracy and at the average in literacy, coming in 23rd and 21st respectively.

With the inclusion of the 9 new countries, the relative performance of England and Northern Ireland has improved from the rankings in the initial report. However, this change cannot be viewed too positively. Several of the new countries, most of which scored below the average and below England and Northern Ireland, tend to be poorer and less-developed than either England or Northern Ireland. Thus the fact remains that even in this new report, the performance of England and Northern Ireland is still below what we might hope to see given the size of our economy and how long our education systems have been in place.

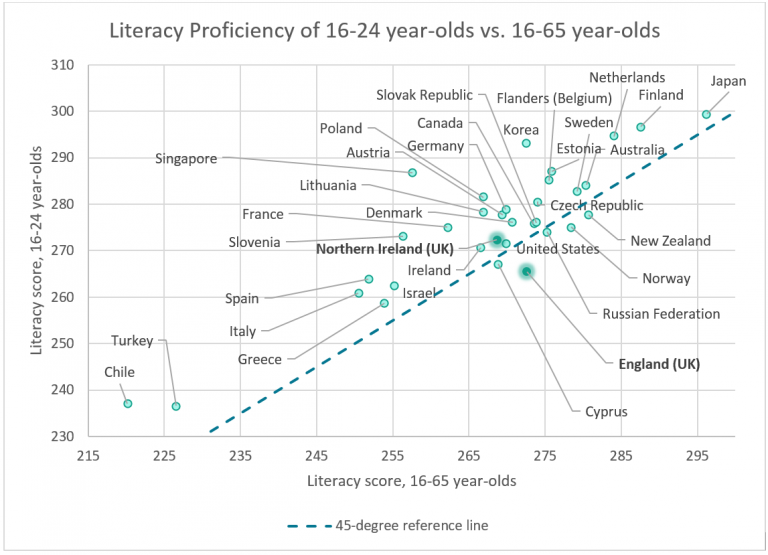

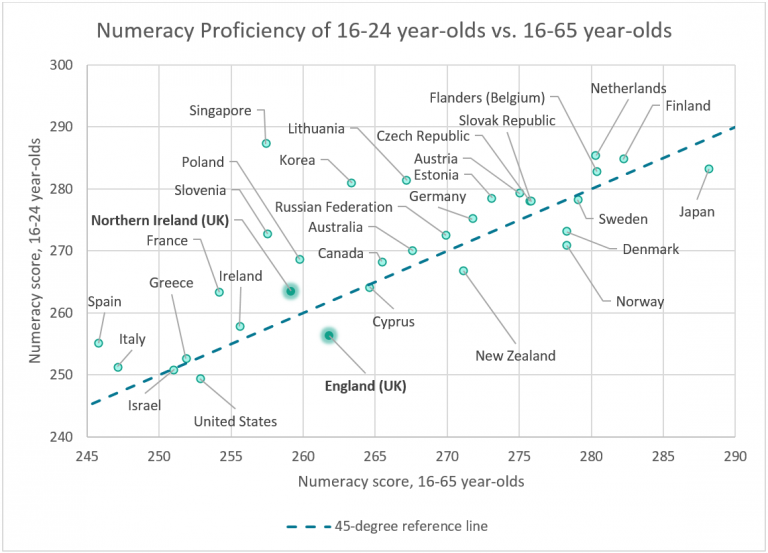

What is more discouraging, though, is the performance of our young people. Adults aged 16-24 in England and Northern Ireland were some of the poorest performing in the world, scoring below average in both literacy and numeracy. Moreover, England was one of the few countries where the average scores of our 16-24 year-olds was lower than the overall average for the country. The graphs below compares the literacy and numeracy results of 16-24 year-olds to the overall averages in their countries. The 45-degree reference lines show where the 16-24 year-old scores are equal to the overall average. Countries above the reference lines are those where young people do better than the overall average, and countries below the reference lines are where young people do worse. England falls in the latter category for both literacy and numeracy.

These results from our young people are greatly concerning. Young people are the workforce of the future, and if they possess low levels of basic skills then there is the potential for future productivity to stagnate as the older generation exits the workforce. With UK productivity at its lowest on record[vi], it is even more important that the skills of young people improve to competitive levels.

In addition to cognitive skill measures, the Survey of Adult Skills collected information on the earnings of its respondents. The OECD’s report uses this information to calculate the wage returns to skills in each participating country. England had the highest wage returns to literacy of all surveyed countries: a one standard deviation increase in literacy proficiency in England is associated with a 12.2 percent increase in hourly wages. England also had the highest percent of its wage variability explained by proficiency in literacy and numeracy. Similarly, Northern Ireland had relatively high returns to literacy, with a 7.34 percent increase in wages associated with a standard deviation increase in literacy proficiency. The fact that England and Northern Ireland had such high wage returns to skills coupled with relatively low levels of skill indicates that poorly skilled workers in England and Northern Ireland could be losing a substantial amount of potential income.

It is therefore quite manifest that the workforce in England and Northern Ireland – and possibly across the UK – requires upskilling, particularly in an uncertain post-Brexit economy. There are two ways that the skills of the workforce can be improved. The first is by developing the skills of adults who are currently in the workforce, through adult education and training programs. A 2014 BIS report used the literacy scores from the 2012 Survey of Adult Skills and the results of the 1996 International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS) to demonstrate that literacy scores of adults in England of the same generation improved as they aged from taking the IALS at age 16 to taking the Survey of Adult Skills at age 32. This is evidence of an unusually large “aging effect”, meaning that much of the score differentials between age groups in England can be attributed to factors that have to do with aging, like work experience and training, as opposed to the different age groups experiencing different quality of education when they were in school (which would be a “cohort effect”). The BIS report goes on to suggest that the significant aging effect could be an indicator that “the skills levels that young adults in England reach at the end of compulsory schooling are insufficient for everyday life and work and so they are required to continue to improve on these skills through further education and training in higher education or when they enter work.” [vii] Given the aforementioned poor performance of 16-24 year-olds, the possibility that these young people will continue to develop their skills after entering the workforce and make up for their current deficiency is a positive sign.

To emphasise further the importance of post-compulsory education and learning, the Survey of Adult Skills, which collects information on whether or not a respondent is participating in training (job-related or not) shows that higher levels of literacy proficiency are associated with a higher percent of respondents participating in training. Over 75 percent of respondents in England and Northern Ireland who scored above a level 4 in literacy said they were participating in some sort of training. By contrast, less than 30 percent of respondents who scored below level 1 in literacy said they were participating in training.

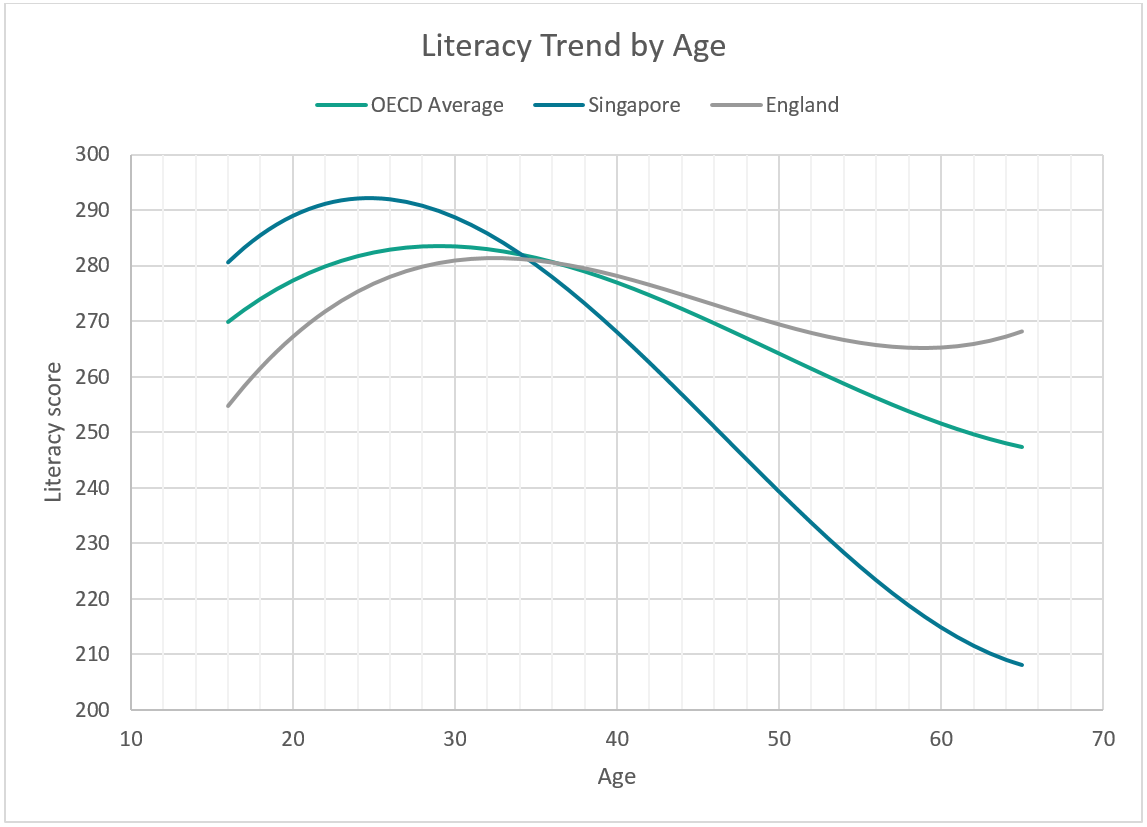

A second way to improve the skills of the UK’s future workforce is to improve the education of young people before they reach working age. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which was most recently assessed in 2012, shows that 15 year-old students in the UK only scored at the OECD average in mathematics and reading.[viii] If we want to keep our workforce from continuing to fall behind in skills, the goal should be to raise student achievement above average. Ostensibly, improving the scores of school-age students seems difficult if the skills of the older generations, the parents and teachers of the younger generation, are merely average or below average. However, the newly published Survey results from Singapore indicate that such improvement across generations is indeed possible. Singapore, which was one of the 9 countries to participate in the Survey’s second round, had an overall score that was below average in literacy and numeracy. But when looking just at young people, Singaporeans aged 16-24 scored the highest of all surveyed countries in numeracy and ranked 6th in literacy. The high skill level of young people in Singapore can also be observed in the 2012 PISA results, in which Singapore’s students came 2nd in mathematics and 3rd in reading and science out of 65 countries and regions. The Survey of Adult Skills shows that Singaporean young people also scored near the top for problem solving in technology-rich environments even while their oldest population scored near the bottom. Furthermore, less than 10 percent of students in Singapore do not acquire basic skills.[ix]

The OECD concludes from the Survey results that the differences in Singapore’s results across age groups are largely attributable to a “cohort effect” (as opposed to the aforementioned “ageing effect”), meaning that the different generations in Singapore experienced vastly different quality of education. While literacy skills on average across countries tend to peak at around age 30 and gradually decrease after that, in Singapore literacy peaks before age 25, and the decrease thereafter is much steeper than average. The trend in England is more similar to the OECD average than to Singapore, though the scores of the youngest respondents in England start out below the OECD average and then catch up by age 35, which could be evidence of the aging effect described above.

*This trend data for this chart is copied from the OECD report except the England/N. Ireland trendline, which was derived from the UK public use file. The trendlines all use a cubic estimation, which the OECD determined gave the most accurate approximation.

Highly-skilled young people are vital to the future of a country’s economy; not only are young people the future of the workforce, but there are more job opportunities for the highly skilled. The OECD reports steep growth in occupations associated with highest average skill scores and either stagnation or even decrease in occupations associated with lower average skills. The latest Survey results show the potential for countries like Singapore to produce highly skilled young people by drastically improving the quality of their education systems, even if the skills of their older generations are on average quite low. This is not to say that Singapore’s approach to education, which like those of other high-performing Asian countries is sometimes seen as controversial[x], should be replicated in the UK. Nonetheless, as a case where relatively poorly skilled adults are raising a generation of highly skilled young people, it can be viewed as an encouraging sign that the UK could, with the right reforms, raise the skills of its young people. While this in itself should be a goal of education policymakers, the UK’s low productivity levels and economic uncertainty make the case for improving the workforce – both through improving the quality of the education system and increasing access to adult education and training – even stronger.

Sources

[i] BBC (2016), “Viewpoint: Brexit puts UK on new economic path”, www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-36619123

[ii] BBC (2016), “Five Challenges for the UK when leaving the EU”, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-36575186

[iii] UKCES (2014), “The Future of Work: Jobs and skills in 2030”, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/303334/er84-the-future-of-work-evidence-report.pdf

[iv] OECD (2016), “Skills Matter: Further Results from the Survey of Adult Skills”, www.oecd.org/education/skills-matter-9789264258051-en.htm

[v] OECD (2013), “OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills”, www.oecd.org/skills/piaac/Skills%20volume%201%20(eng)–full%20v12–eBook%20(04%2011%202013).pdf

[vi] Guardian (2016), “UK productivity gap widens to worst level since records began”, www.theguardian.com/business/2016/feb/18/uk-productivity-gap-widens-to-worst-level-since-records-began

[vii] BIS (2014), “Young Adults’ Skills Gain in the International Survey of Adult Skills 2012”, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/384201/bis-14-1034-young-adults-skills-gain-in-international-survey-of-adult-skills-2012.pdf

[viii] OECD (2013), “Snapshot of performance in mathematics, reading, and science”, www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/PISA-2012-results-snapshot-Volume-I-ENG.pdf

[ix] OECD (2015), “Universal Basic Skills: What Countries Stand to Gain”, www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/9115061e.pdf?expires=1467107864&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=CF8D96DBEFD82E03D668380AEF9339E5

[x] ABC (2016), “Singapore schools: ‘The best education system in the world’ putting significant stress on young children”, www.abc.net.au/news/2016-01-06/best-education-system-putting-stress-on-singaporean-children/6831964