Children are entitled to be registered for free school meals (FSM) if their family earns a very low income and is in receipt of certain social security benefits.[1] As well as ensuring a child receives lunch at school, being registered for FSM is a gateway to substantial additional support and provision. For example, children are funded to attend the Holiday Activities and Food Programme.[2] Many schools offer discounts for extra-curricular clubs and trips to FSM-registered pupils. Some LAs offer additional grants and vouchers, and subsidise the cost of school uniform if a child is recorded as FSM-eligible.[3]

FSM registration at any point over a six year period also means that a pupil is flagged for Pupil Premium. Pupil Premium children are required to be prioritised for enrichment and education within their school.[4] This is intended to direct resources to children relatively less advantaged in their lives and wider context than their peers.

A corresponding pot of funding is allocated to each school according to the number of Pupil Premium children they have registered. This is currently £1,035 per child during the primary years, and £1,455 throughout secondary. The number of children eligible for FSM in the past six years is also factored into other aspects of education funding, including the National Funding Formula Schools Block.[5]

We know already that registration for FSM is incomplete and uneven

Although the number of pupils being registered for FSM is therefore instrumental in channelling resources, entitlements, and funding, both at the pupil and school-level, not all children meeting the criteria for FSM are registered. For years, it has been known that registration for FSM is not complete, and that this under-registration varies according to family and area characteristics.[6]

The Department for Education last investigated under-registration in 2013, and estimated that 11% of entitled families were not claiming FSM at this time. It also found wide variation by area, with nearly 40% of entitled pupils not registered in the most extreme local authority.[7] Research suggests that factors like local poverty levels and family language background are associated with under-registration for FSM.[8]

Under-registration in reception and key stage 1

But what about children’s age? Are pupils at different stages of education – early primary school, late primary school, secondary school – more or less likely to be registered for their FSM entitlements? What can this tell us about who may be missing out on support and provision?

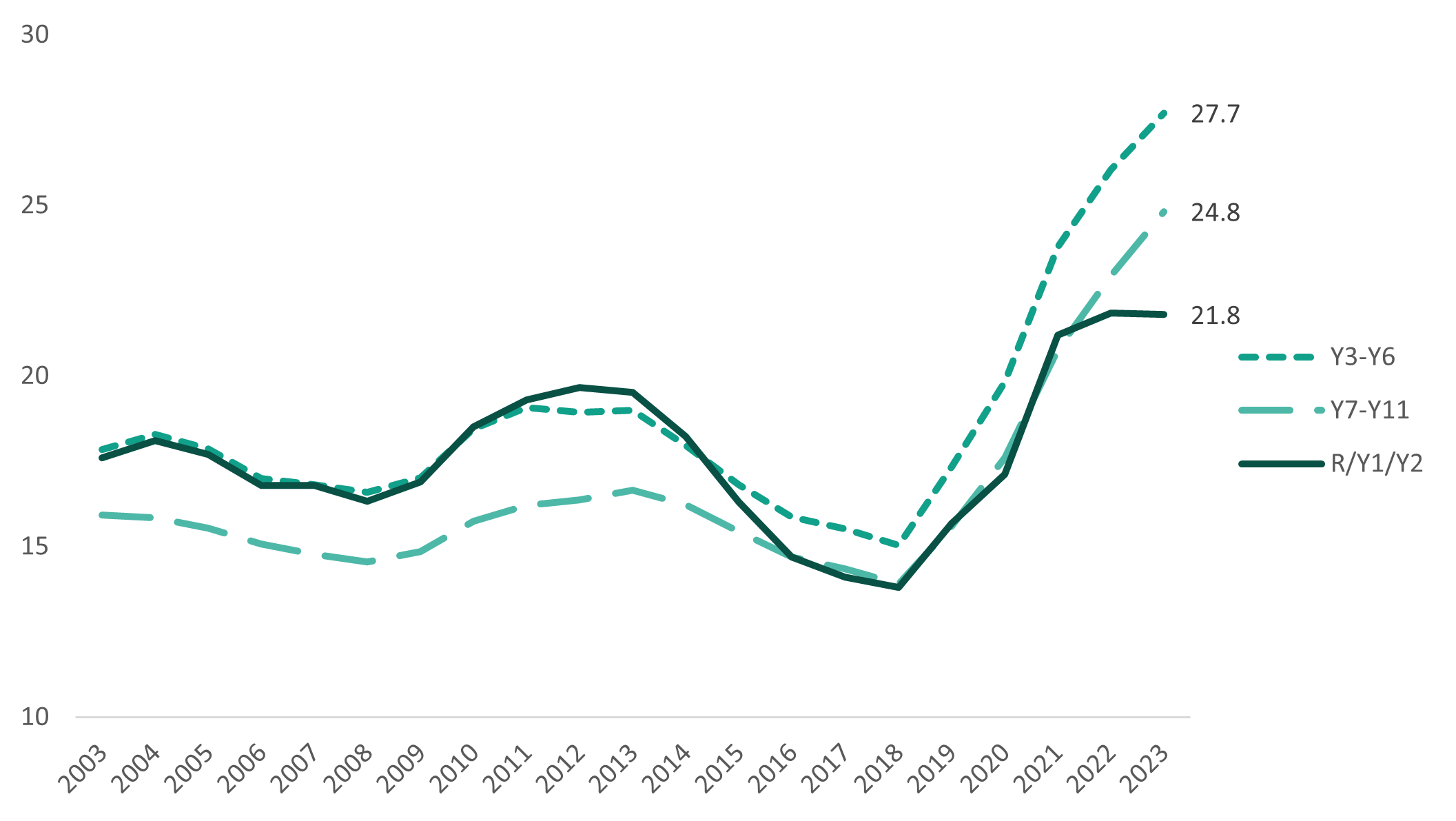

Figure 1 shows the percentage of children registered for FSM at each stage of education. Until 2014, those in early primary school (reception-year 2) were as likely as those in late primary school (year 3-year 6) to be FSM-registered, and more likely than those in secondary school. But after this, pupils in early primary become less likely than those in late primary to be registered, and by 2023, 22% of early primary children were registered, compared to 28% of late primary children, and 25% of secondary children.

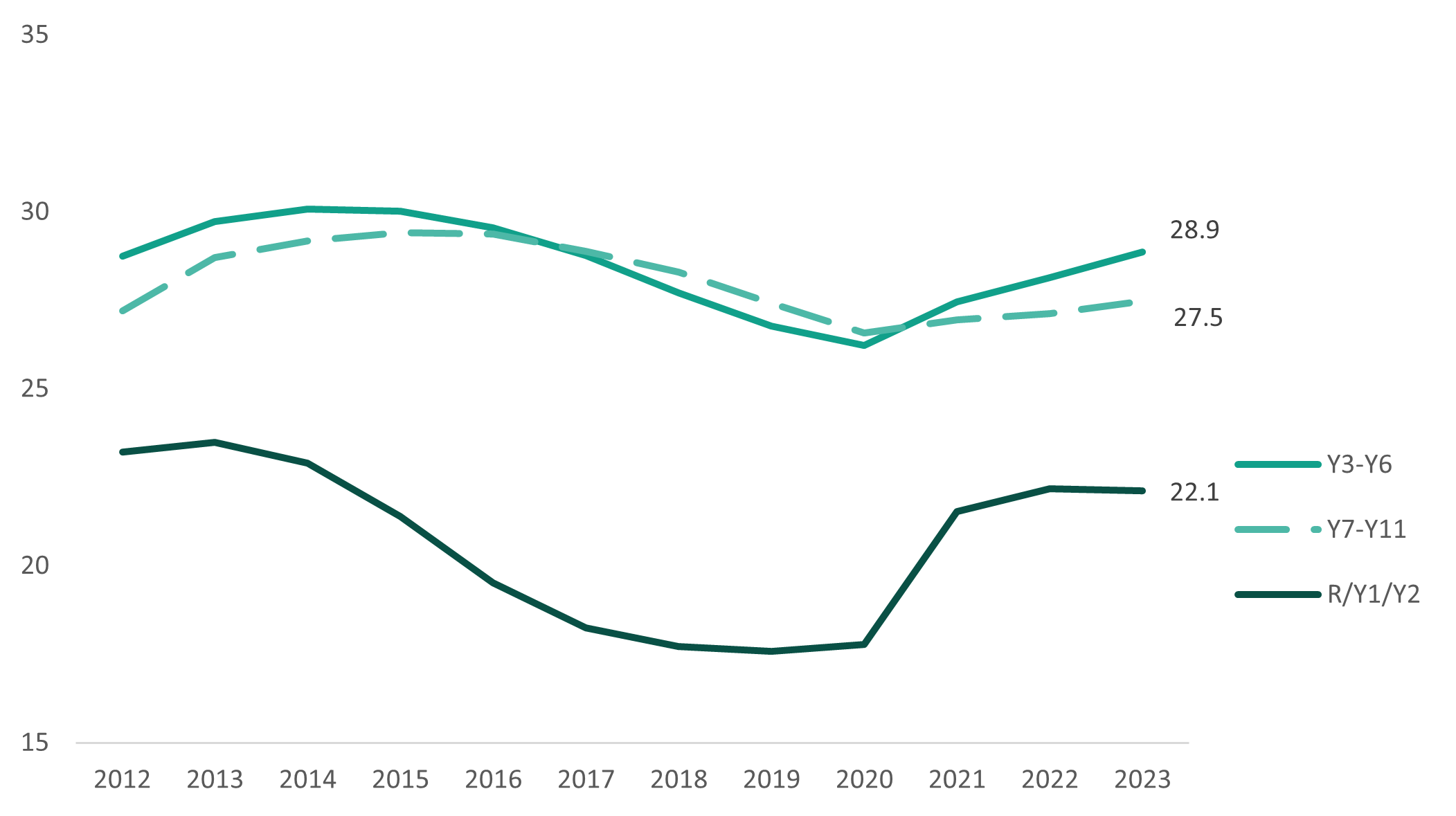

Figure 2 shows the percentage of children at each stage recorded as ever being FSM-eligible in the past six years, and therefore allocated Pupil Premium. Since the Pupil Premium was rolled out, in 2012, children at the beginning of primary school have always been less likely to be in receipt than their older counterparts.

Figure 1: Percentage of pupils at each stage of education recorded as FSM-eligible in the National Pupil Database

Figure 2: Percentage of pupils at each stage of education recorded as eligible for FSM in the past six years (Pupil Premium) in the National Pupil Database

The reasons for these patterns are fairly obvious: for example, the longer a pupil is in education, the more years they have to ‘become’ FSM, and therefore Pupil Premium. The introduction of universal infant free school meals in 2014 – while a success in other ways – has disincentivised registration.[9] But despite being explicable, these patterns are highly problematic. They mean that the youngest school children in low-income, FSM-entitled families are the least likely to benefit from the resources and provisions intended to be channelled their way and to compensate for under-resourcing outside of school. Children are missing out, and, given the importance of the earlier years in laying foundations for later progress and development, this is not an optimal distribution of resources.

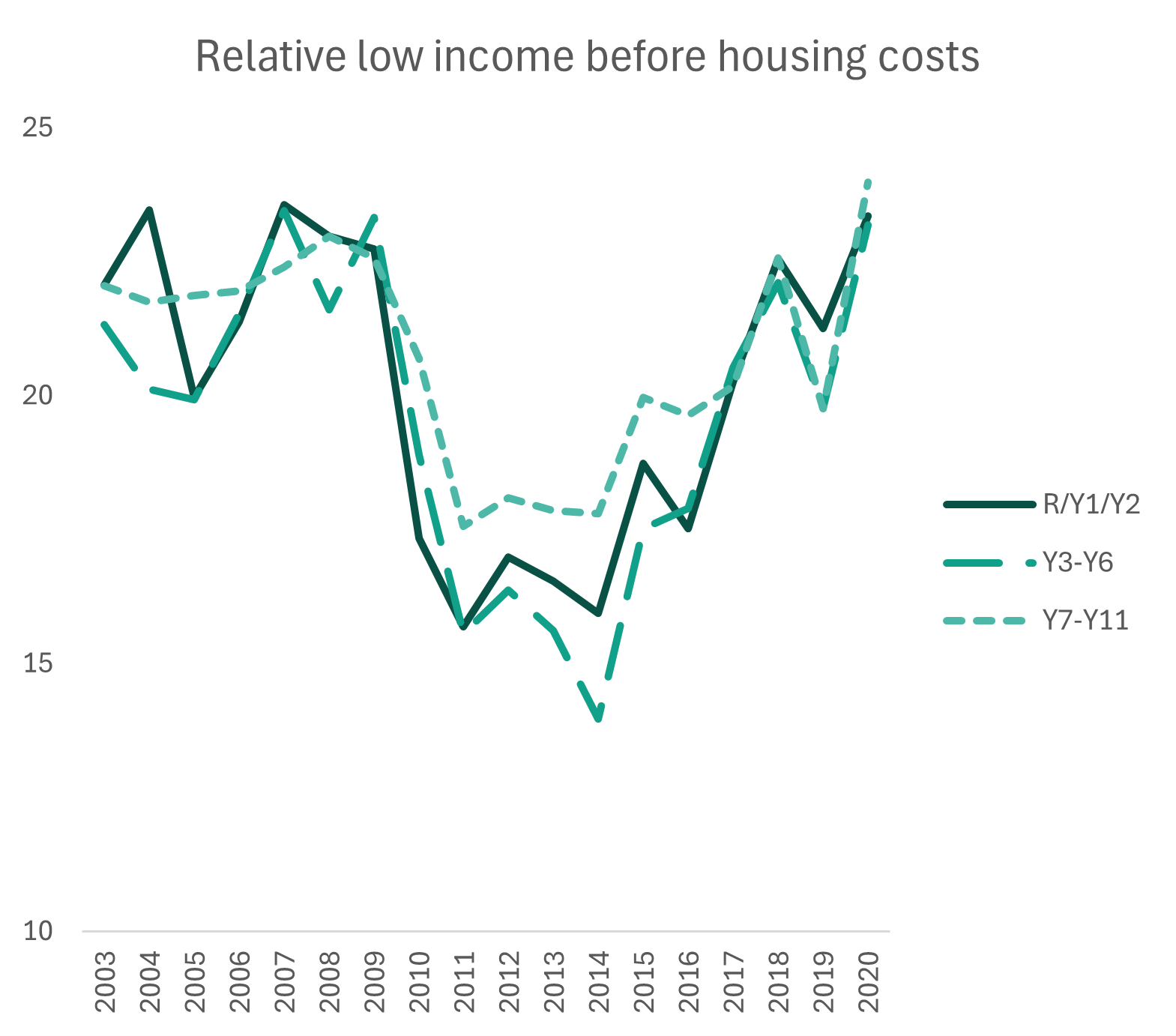

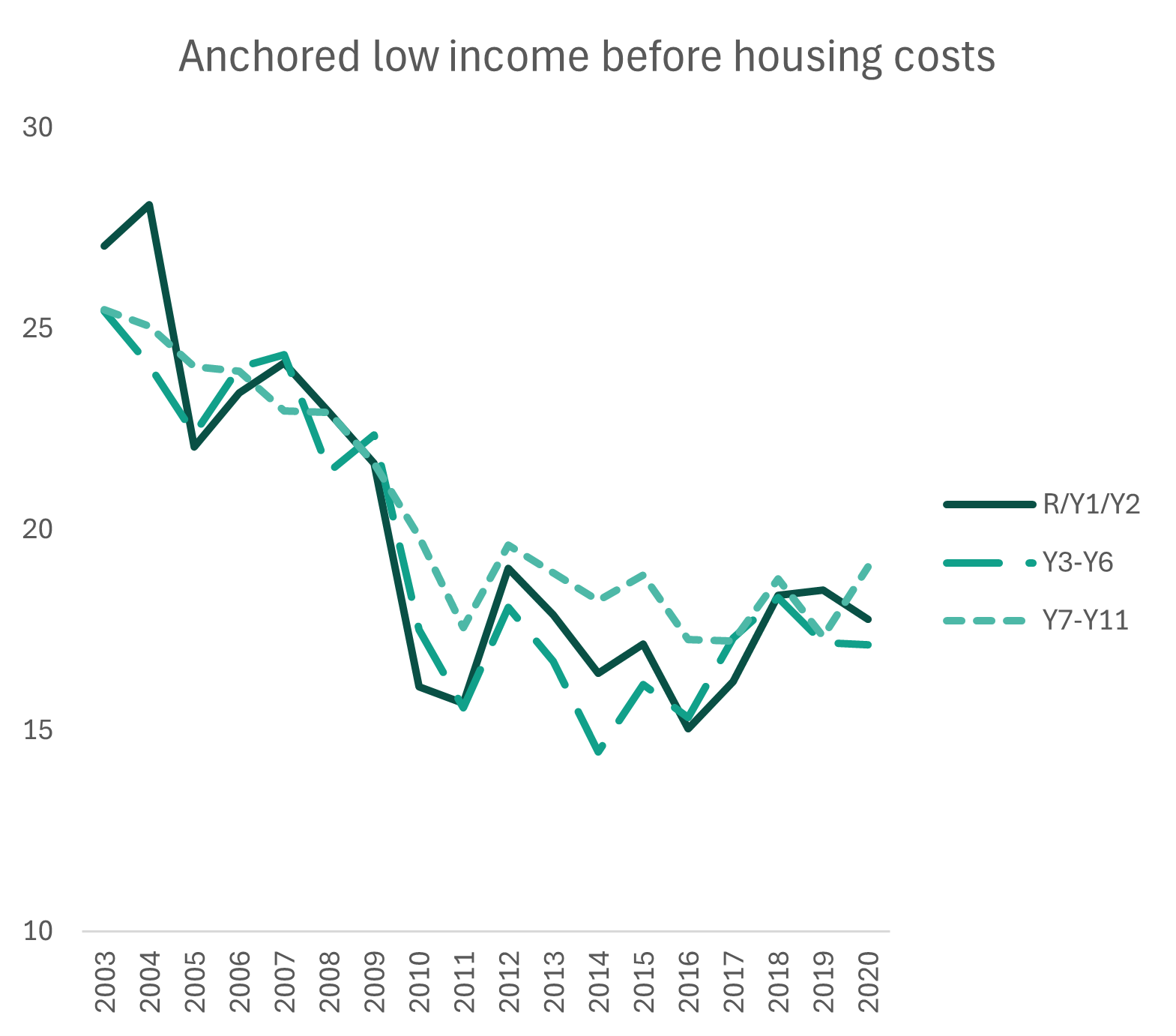

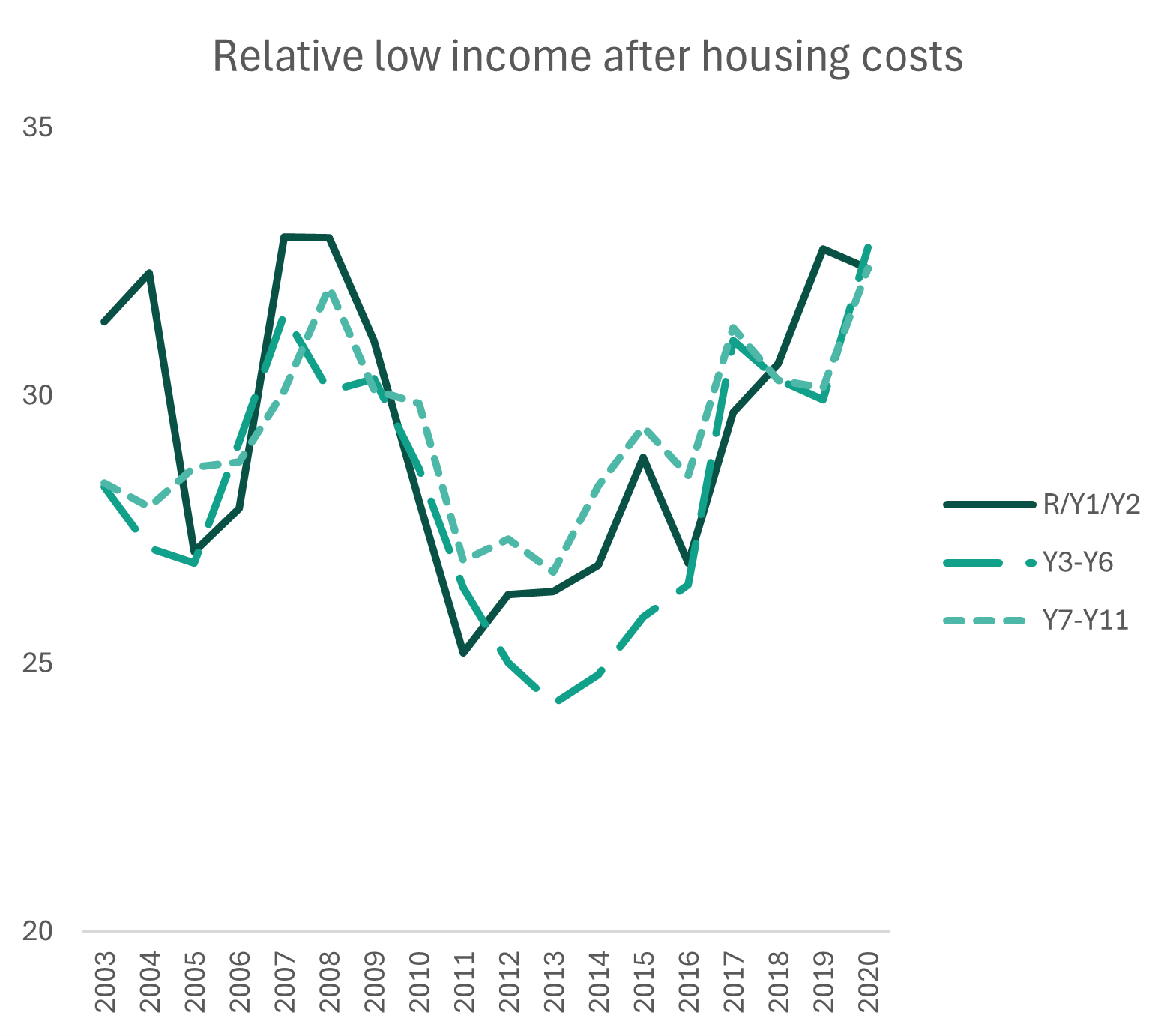

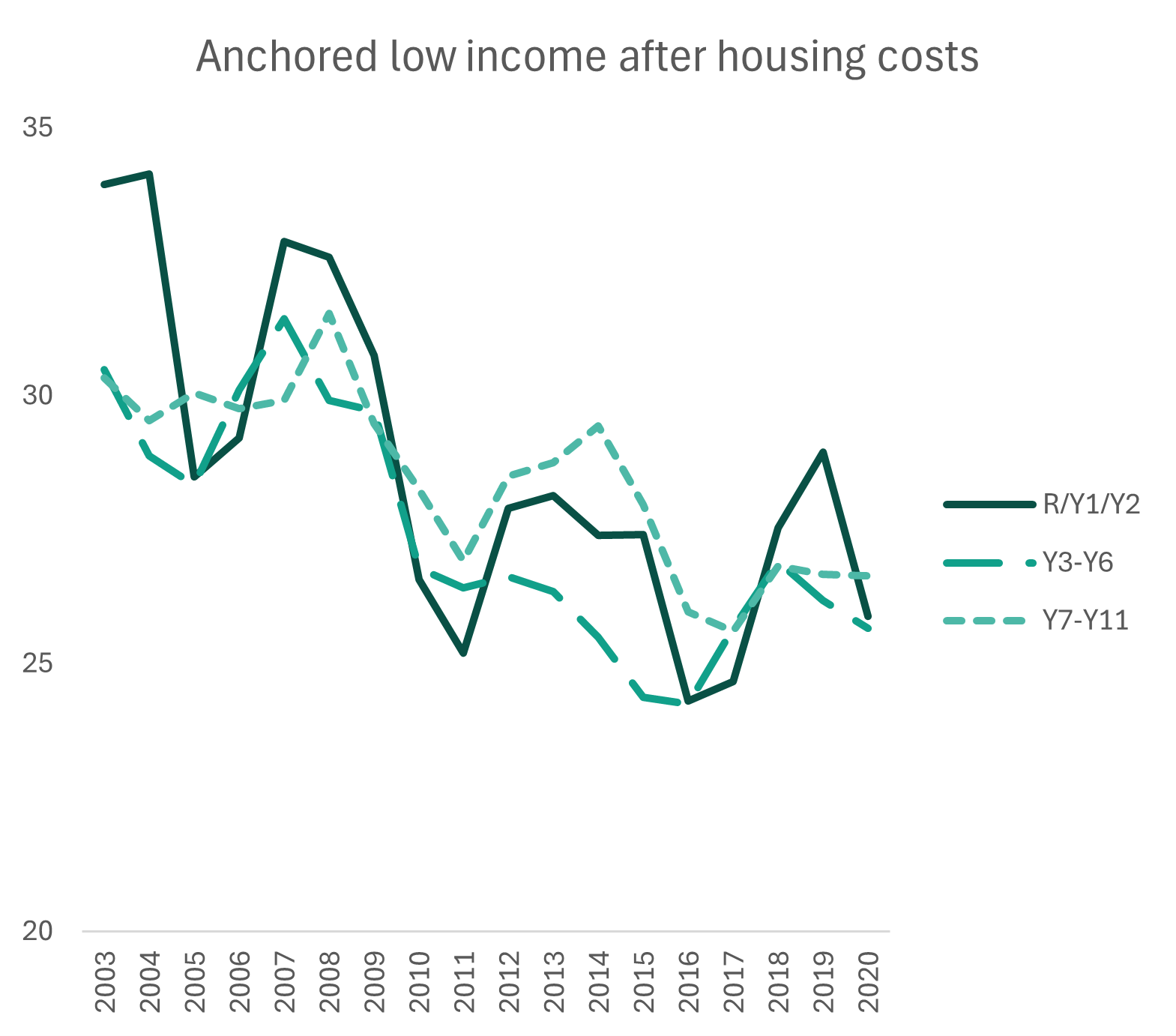

Statistics on poverty levels among children of different ages – taken from the DWP’s Household Below Average Income dataset – emphasise that these patterns of increased chances of FSM under-registration among younger primary children do not reflect differences in need. Figure 3 shows that, over the years, according to a variety of different measures, children in early primary school are generally as likely to be in poverty as those in later primary school.

Figure 3: Percent of pupils at each stage of education estimated using the Households Below Average Income dataset to be living in families in poverty, according to various measures[10]

Could auto-enrolment help?

How could this under-registration of the youngest school children be tackled? One solution that could contribute to redressing the undercount is some form of auto-enrolment.

Government departments hold information that, for many children, can be matched to determine whether they are entitled to be registered for FSM. This is based on centrally held details of parent/carer(s)’ known receipt of welfare benefits and known income-level. It is currently used for the Eligibility Checking System, which is utilised by schools and local authorities to determine a child’s FSM entitlement.[11] For many pupils, this data could be used to assign eligibility, without the need for their parent/carer(s) actively to apply.

Auto-enrolment is not without its own problems and issues, however. Firstly, it would not fully identify all FSM-entitled children. Not all entitled families sign up to claim the welfare benefits that confer FSM-eligibility. Low-income children in families with no recourse to public funds would not be identified through auto-enrolment. And where a child has responsible parents/carers living across different households, centralised data matching may be problematic.

Secondly, auto-enrolment raises legitimate concerns regarding choice, data sovereignty, and privacy. Concerns, however, should be weighed against the potential benefits for pupils of being registered for FSM, and against evidence that children in some families are unregistered not through choice but through a lack of knowledge of the system. There is also evidence that language barriers and bureaucratic complexity can prevent some families from accessing their entitlements.[12]

The Department for Education has stated that there are ‘complex data, systems, financial and legal implications’ to auto-enrolment.[13] However, knowing what can be gained for their pupils and schools through FSM-registration, a number of local authorities have begun to instigate their own auto-enrolment exercises.[14] In practice, this consumes more public resources and is less efficient than a centralised process. And the current situation is one where the implications and associated risks of auto-enrolment are being born by local authorities, as they attempt to identify the children within their area who are FSM-entitled, and to draw in the resources intended by central government to be allocated according to FSM.

Financial implications

So – alongside an opt-out mechanism for families who do not wish their child to be recorded with FSM or flagged as Pupil Premium – centralised auto-enrolment, coupled with an opt-in registration for those not captured through data matching, could ensure fuller coverage and registration of FSM-entitled pupils.

In terms of financial implications, and returning to the particular focus of this blog – the pronounced under-registration of early primary-aged children – we can begin to ask: what would the additional cost of this fuller coverage be, were pupils in reception and key stage 1 signed up at the same rates as those in key stage 2 – that is, at rates closer to those intended by national FSM policy?

There are a number of channels through which this would play out, because FSM is a gateway to various associated entitlements, including holiday provision. But taking only the funding allocated from central government through the Pupil Premium and the National Funding Formula Schools Block, we can roughly estimate the uptick. We calculate that around £350m would additionally be required in 2024-25, were the same percentage of children registered as FSM-eligible in early primary as late primary.[15]

Arguably, this is not an insubstantial amount of money – but it is one necessary cost if policies on supporting less advantaged and resourced children are to be implemented as intended. The amount does not represent an increase in remit or an expansion of provision – it simply estimates some of the true cost of the policy, were it to be implemented more completely, and disparities in registration by age eliminated.

Potential improvements through auto-enrolment

We have shown throughout this blog that there is substantial under-registration for FSM, particularly among children at the beginning of primary school. This means that many of the youngest do not access holiday provision and food, subsidised activities, trips, prioritisation through Pupil Premium, and other resources – resources intended by central government policy to be channelled to those in families with the lowest incomes. Additionally, schools and local authorities do not receive the full amount of funding intended to provide for children in low-income families.

The administrative and legislative practicalities of centralised auto-enrolment for FSM should therefore seriously be explored and considered as a solution that would go some way towards ensuring that the youngest pupils – as well as other under-registered groups – do not miss out on resources, provision, and equalising opportunities.

Acknowledgements

This blog is part of a research project, What has ‘Free School Meals’ measured and what are the implications?,[16] funded by the Nuffield Foundation.

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance social wellbeing. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in Education, Welfare, and Justice. The Nuffield Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. The Foundation has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Website: www.nuffieldfoundation.org Twitter: @NuffieldFound

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance social wellbeing. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in Education, Welfare, and Justice. The Nuffield Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. The Foundation has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Website: www.nuffieldfoundation.org Twitter: @NuffieldFound

This work contains statistical data from ONS which is Crown Copyright. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates. Analysis was carried out in the Secure Research Service, part of the Office for National Statistics.

This publication includes analysis of the National Pupil Database (NPD): https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/national-pupil-database

The Department for Education is responsible for the collation and management of the NPD and is the Data Controller of NPD data. Any inferences or conclusions derived from the NPD in this publication are the responsibility of the Education Policy Institute and not the Department for Education.

It also includes analysis of: the Department for Work and Pensions. (2023). Households Below Average Income, 1994/95-2021/22. [data collection]. 17th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 5828, DOI: http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5828-15