Schools in England continue to face a number of challenges when it comes to funding, despite significant increases in recent years. Rising energy prices, inflation, growing calls on the high needs budget, and increasing staff costs have already squeezed school budgets across the country.

Over the coming years, the system is also going to have to manage the issue of falling rolls.

Pupil numbers are approaching their peak and are estimated to fall to similar levels to those seen before the post-millennium ‘baby boom’ by 2032. With school funding so closely tied to pupil numbers, fewer pupils mean smaller school budgets, but school costs don’t necessarily fall in the same way.

These challenges are multi-faceted and are already affecting schools in different ways based on their demographics, location, and historic funding arrangements. The fall in pupil numbers has already begun amongst the primary aged population. As pupil numbers fall and these financial pressures build many – particularly smaller – schools, academy trusts, and local authorities will be forced to take difficult decisions, such as cost-cutting, amalgamations, and ultimately school closures.

Amidst this challenging environment and complicated system, it can be difficult to parse the real impact of policies relating to school funding. Small adjustments to percentages can represent billions of pounds and huge changes to individual schools, while commonly reported national figures hide the disparities baked into the system. Policy announcements often take place long in advance, while their effects aren’t usually felt until years down the line.

As we head towards a general election, it is even more important to understand the medium- and long-term implications of policy announcements. To support school leaders, parents and the electorate with this, we have developed a new school funding model that is aimed at modelling the impact of different funding-related proposals on local authorities, constituencies and individual schools. The model replicates the Department for Education’s method of calculating notional school-level allocations for mainstream, state-funded schools through the schools block of the national funding formula (NFF) – the main source of school funding.

The model allows us to adjust many features of the NFF such as the per-pupil factor values and protective elements like the ‘funding floor’, letting us see the types of schools and pupils who are likely to be the winners and losers of any proposal, how existing funding could be redistributed, or what the cost to the Treasury would be of any new spending.

Similarly, we can highlight geographic disparities that tweaks to the formula may address or worsen.

Today, we have published a new report, ‘School funding model: Effect of falling school rolls’, that uses our new model to project forward school funding to 2030 using DfE pupil projections, investigating how the decline in pupil numbers is set to affect real terms school funding in England if pupil-led per-pupil funding follows a modest, year-on-year increase.

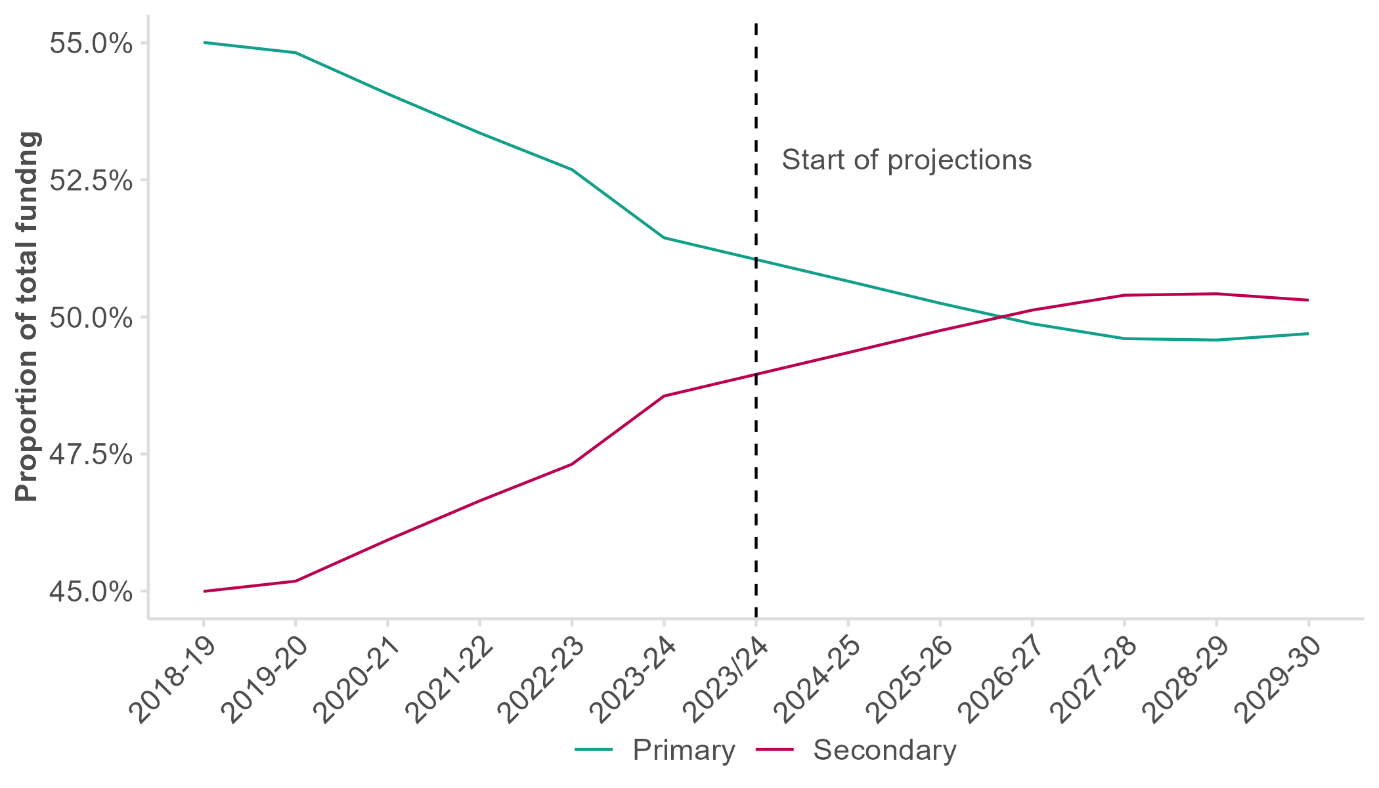

Our analysis shows how the decline in primary pupils is projected to shift the proportion of the school budget spent in each phase by the end of the decade, with secondary funding overtaking primary funding by 2026-27.

Shifting proportions of funding by phase

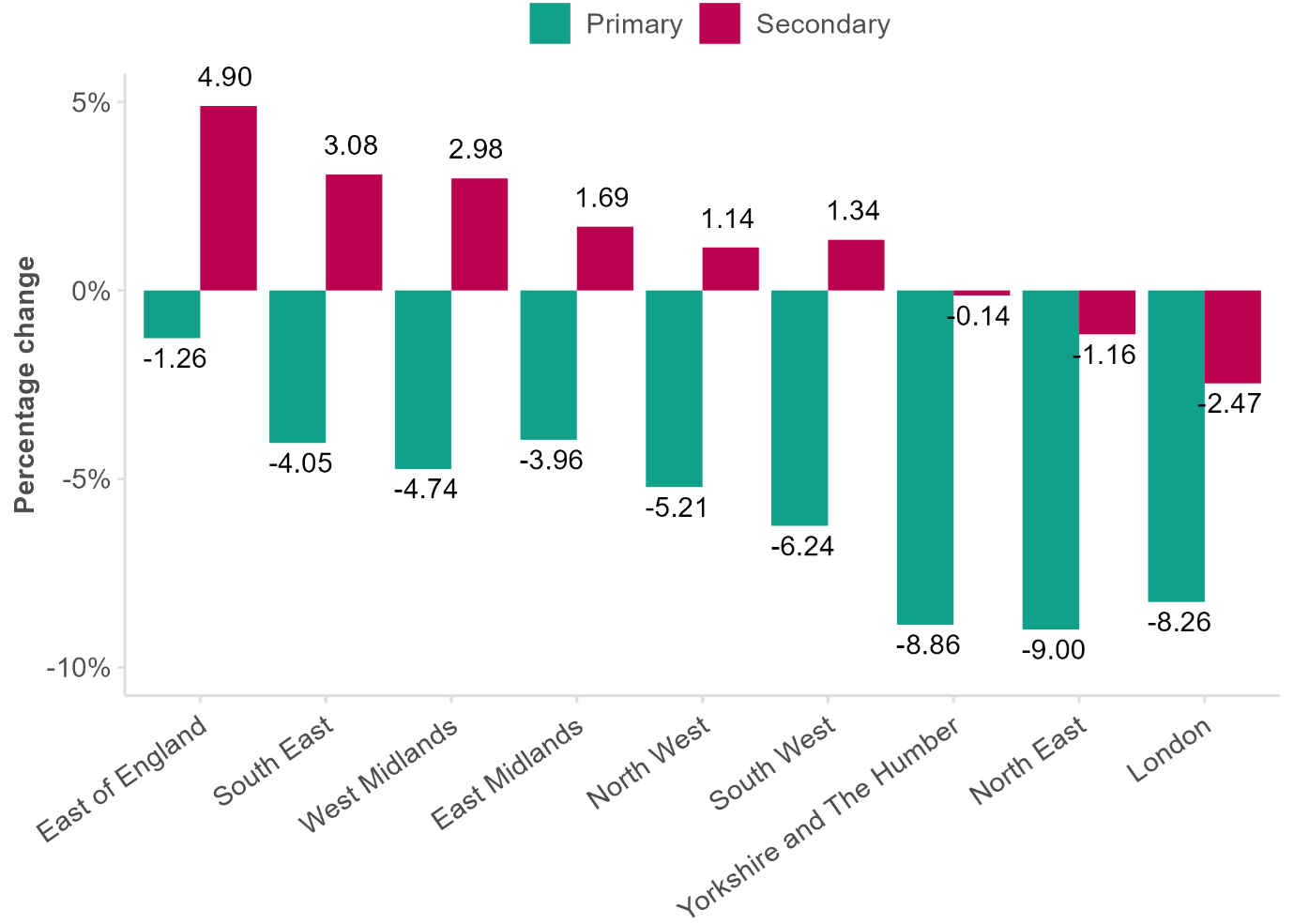

Our school-level approach also allows us to aggregate to any geographic level. We find that between 2023-24 and 2029-30, projected regional demographic changes will result in stark changes in projected funding across the regions of England – with Yorkshire and the Humber, the North East, and London set to see the biggest falls in overall funding.

London and North East projected largest falls in funding at primary and secondary

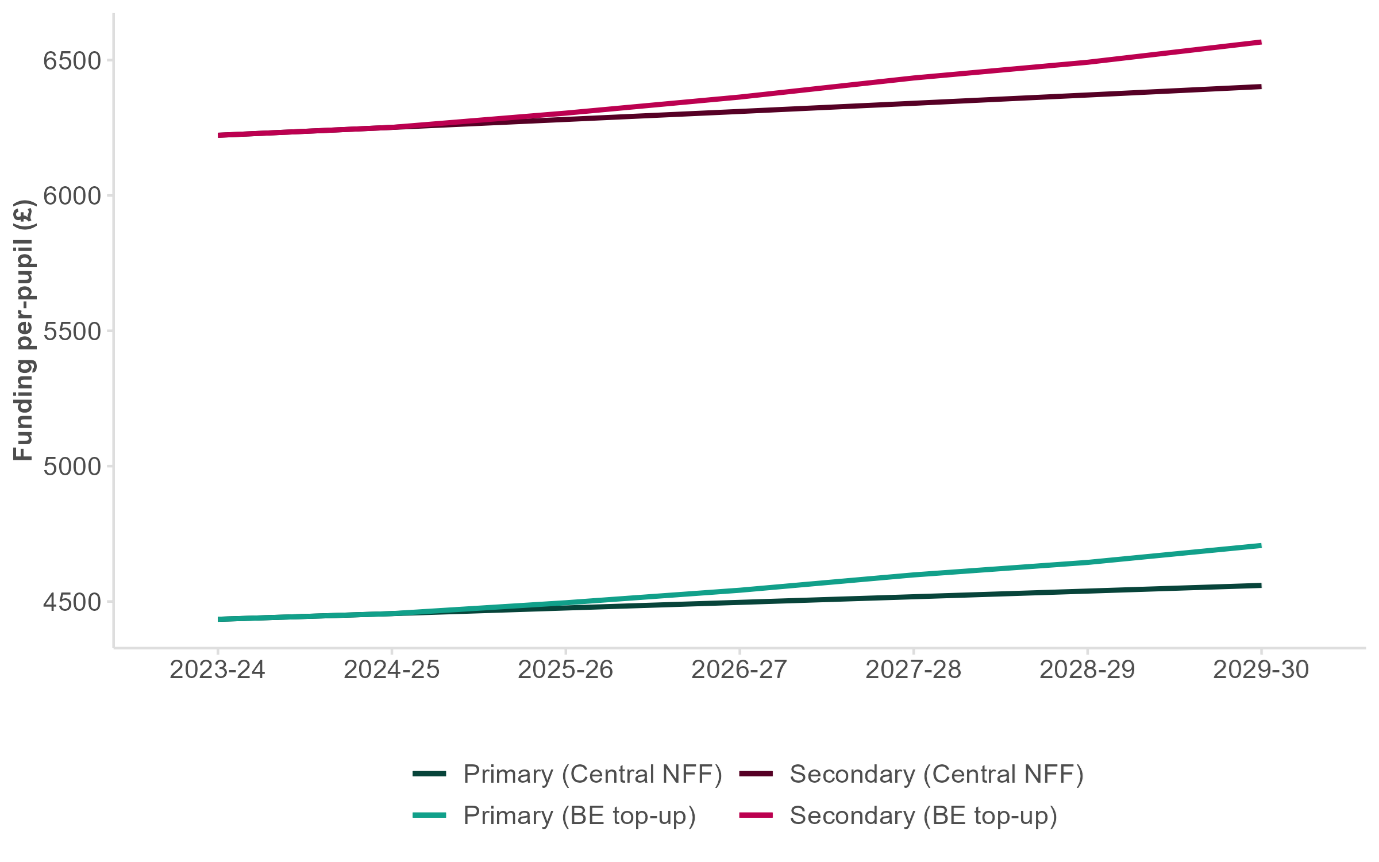

Because of falling rolls overall, a modest increase in real terms per-pupil pupil-led funding (a modelled increase of 0.5 per cent per year) would still result in large savings in overall school spending. We explore how the “savings” created by falling pupil numbers could be reinvested into the basic entitlement factor of the NFF.

Under our model’s assumptions, where pupil-led per-pupil funding increases at 0.5 per cent each year in real terms, total funding through the schools block would peak in 2024-25 at £42.75 billion. By 2029-30, we project this figure will have dropped to £41.63 billion in current prices, creating a compound saving of £3.20 billion over the 5 years between 2024-25 and 2029-30. If this saving was reinvested in the basic entitlement factor, per-pupil funding could rise by £148 for primary pupils and £164 for secondary pupils over the same time period.

Impact of a basic entitlement increase on per-pupil funding

This is intended as an illustration of the scope of the model and the types of questions we explore. It does not represent an EPI policy position, not least because it would weaken the link between pupil characteristics and funding, something we have long argued against.

In the next publication using our model, we will explore in more detail how funding might be better targeted towards disadvantaged pupils, in particular we will explore a formula factor for persistently disadvantaged pupils to help tackle the persistently wide attainment gap for these pupils.

You can read the report, ‘School funding model: Effect of falling school rolls’, here.

You can view our interactive charts for pupil number and funding changes by region, local authority, and parliamentary constituency here.