Increasing proportions of students are relying on living in their own residence during their higher education. Disadvantaged students are most at risk from this trend, with home ownership less likely to be an option and high rental costs more of a barrier. If the government hopes to increase the falling participation of disadvantaged students, it must recognise the increasing number of students who are struggling to meet basic housing costs.

Accommodation consistently ranks among university students’ largest concerns during their time in higher education, with one in two students surveyed reporting fears about the student housing shortage, according to the 2024 National Student Accommodation Survey conducted by Save the Student. In December 2024, a report from Unipol and the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) found that the maximum student loan is now less than the average student rent, leaving many students struggling to meet basic living costs.

The affordability of student accommodation is ever-changing and is driven by a range of factors such as student behaviour and characteristics, local housing supply, and shifts in rental markets. Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) gives an insight into these trends and how they have changed for students at English universities over the past decade.

Where do students live?

The HESA data categorises respondents into broad housing categories, and splits students by type (first years and students in their second or later year).

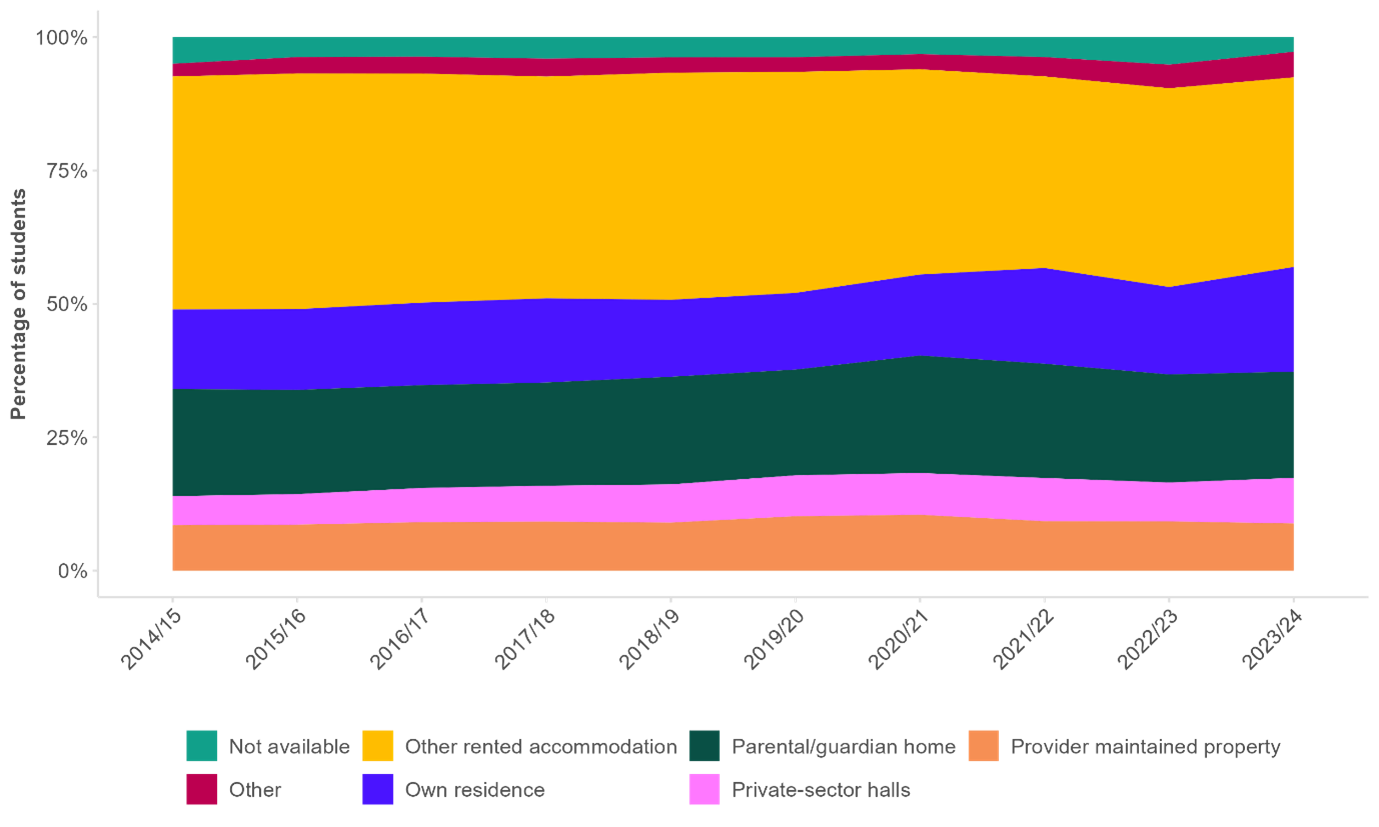

For non-entrants – students in their second year of study or later – the plurality (35.6 per cent) are housed in private rentals in 2023/24, though this share has decreased steadily in the past decade from 43.7 per cent in 2014/15. At the same time, there have been increases in the proportion of students living in a property they own (up to 19.9 per cent in 2023/24 from 14.9 per cent in 2014/15) and private-sector halls (purpose-built student accommodation not owned by a higher education provider), up to 8.6 per cent in 2023/24 from 5.6 per cent in 2014/15.

These shifts mean that in 2023/24, the proportion of second year or later students now living in either their own or their parents’ property (39.5 per cent) now eclipses the total proportion of students living in private rentals.

Proportion of second year or later students by accommodation type, 2014/15 – 2023/24

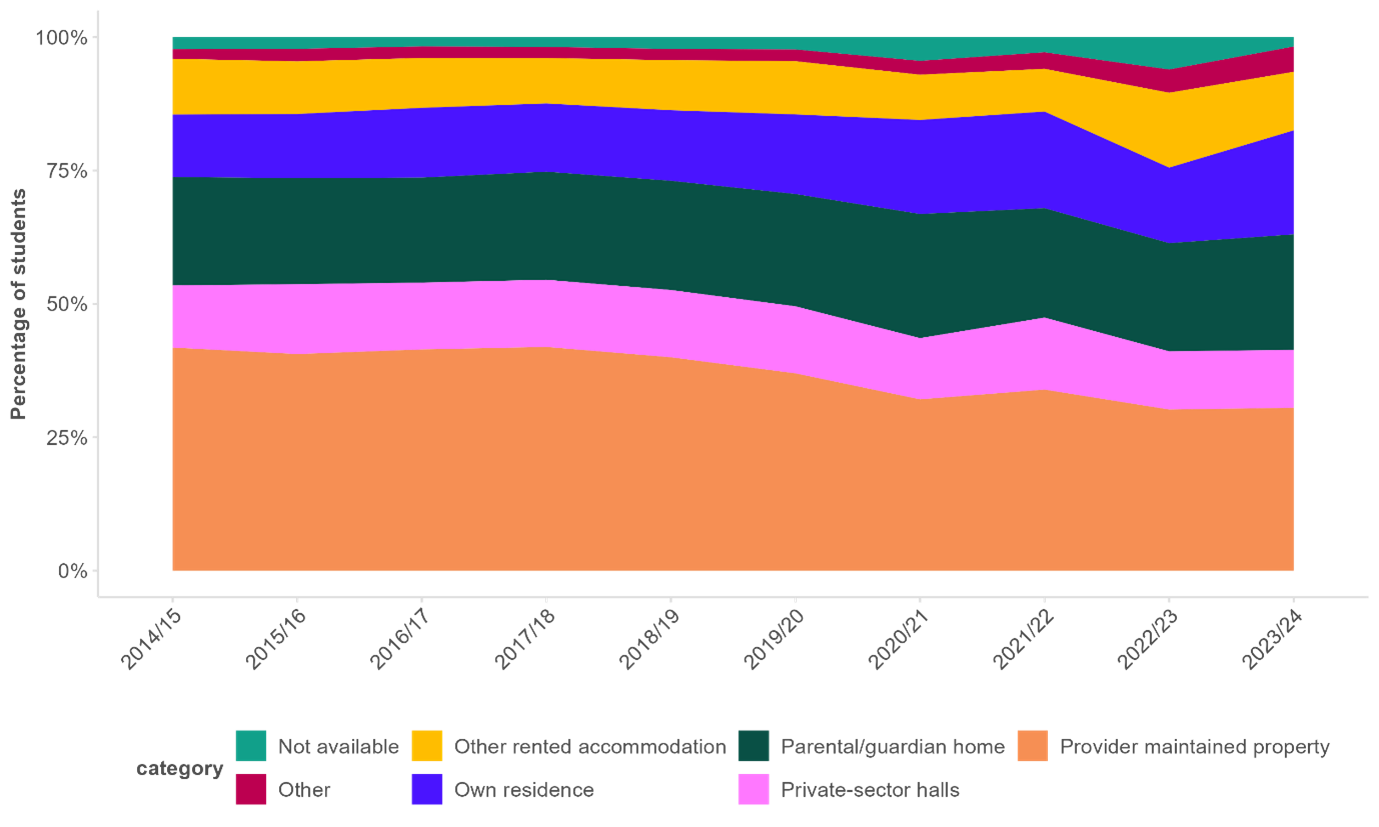

For first years, the picture is predictably different, as many universities guarantee accommodation in halls (often provider maintained) for full-time first year students. As such, this accommodation type makes up the plurality of housing arrangements for first years (30.5 per cent in 2023/24), although this has fallen over the last 10 years from 41.8 per cent in 2014/15. As with later year students, there has been a corresponding increase in first years living in owned residences, increasing to 19.5 per cent in 2023/24 from 11.7 per cent in 2014/15.

Among the other accommodation types, little has changed over this period. A small increase in students living with parents/guardians or in private sector halls was reported in 2021/22, as well as some growth in private rentals in 2022/23.

Proportion of first year students by accommodation type, 2014/15 – 2023/24

Differences across England

Trends in student accommodation vary by region as a result of local market dynamics, higher education provision and provider type. The charts below show student accommodation types by region of provider (rather than where the accommodation in question is located).

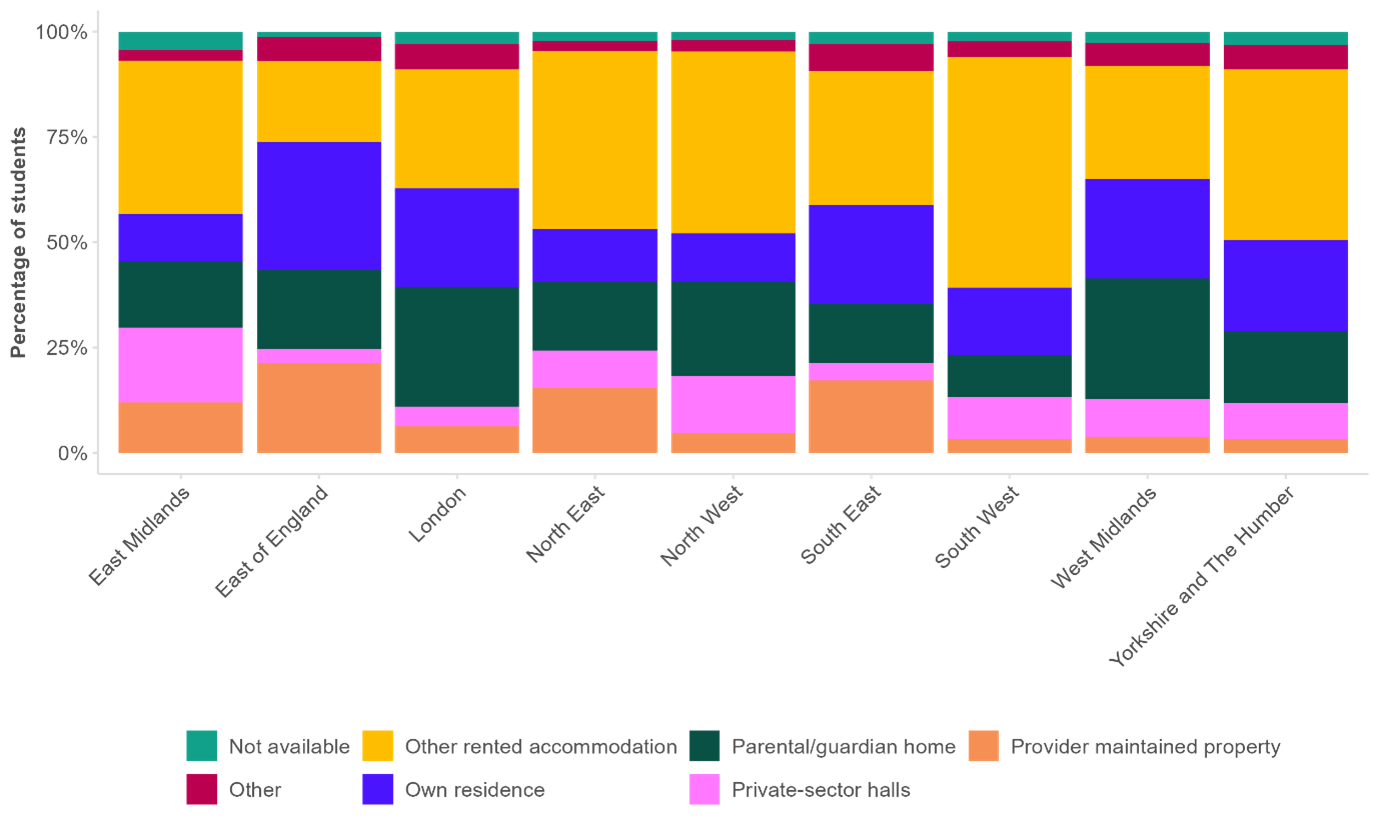

For second year and later students, we can see that despite the domination of private rentals, some regions have a much more diverse mix of accommodation types. In the East of England, the plurality of second year or later students are living in their own properties (30.5 per cent in 2023/24), while in the West Midlands, students are most likely to live with parents or guardians (28.5 per cent in 2023/24).

The South West has the highest proportion of students living in private rentals at 54.7 per cent in 2023/24, while the East of England has the highest proportion of second year or later living in provider maintained properties (21.3 per cent in 2023/24).

Many regions have seen little change in their make-up of accommodation types, with some exceptions; the East Midlands has seen the largest fall in private rentals, now at 36.5 per cent in 2023/24 down from 53.5 per cent in 2014/15. On the other hand, very few West Midlands second year or later students now live in provider maintained properties, now at just 3.8 per cent in 2023/24 compared to 15.3 per cent in 2015/16.

Proportion of second year or later students by accommodation type and region, 2023/24

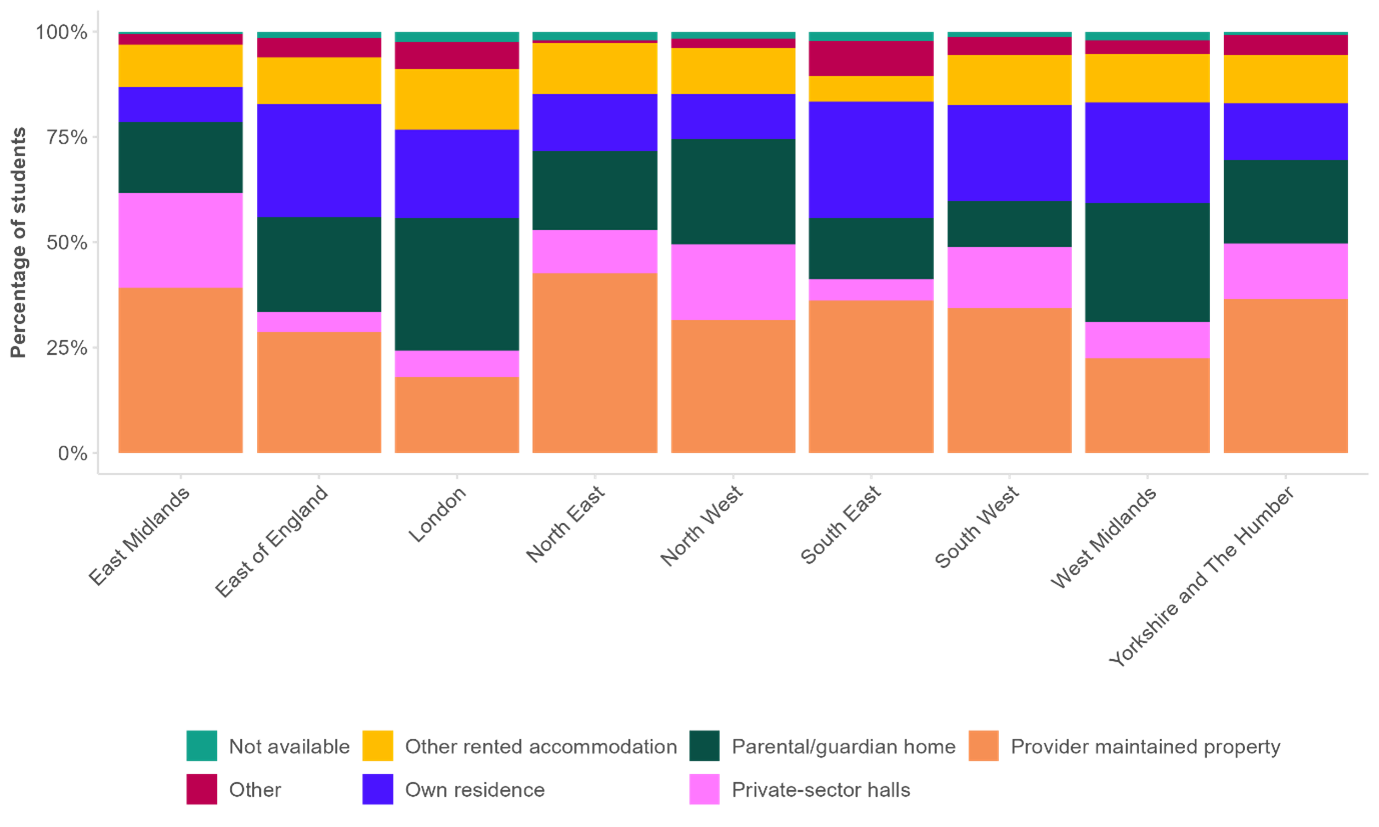

There is also variation in accommodation type for first year students by region. While most first year students in England live in university halls, this arrangement is now most prevalent in the North East (42.6 per cent in 2023/24) and least so in London (18.1 per cent in 2023/24).

First year students in London are instead more likely to live with parents (31.3 per cent in 2023/24), as are first years in the West Midlands (28.3 per cent in 2023/24).

In terms of trends over time, most salient is the decline in provider maintained properties in the South East, which has almost halved in the recent years, now at 36.2 per cent of students in 2023/24 compared to 61.3 per cent of students in 2016/17. Yorkshire and the Humber has seen its share of first year students in private sector halls halve over the same period, down to 13.3 per cent in 2023/24 from 26.3 per cent in 2015/16.

Proportion of first year students by accommodation type and region, 2023/24

The rising costs of living coupled with lower-than-inflationary rises to maintenance loans (and the abolition of the maintenance grant system) appears to have had some long-term effects on student behaviour, with the share of students in rental properties having decreased over the past decade. This change may have driven the observed increases in students living in owned properties or with their parents – but this will never be a realistic option for all students, particularly the most disadvantaged.

For the government to make progress on widening participation, it must also work to limit the barriers of affordability for disadvantaged students once they are in university, and chief among these concerns for students are the costs of basic accommodation.

Without further support for the most disadvantaged students – whether in the form of maintenance grants or uplifts to maintenance loans to reflect the rapid rises in costs in some areas – we risk shutting out students who fear they won’t be able to afford university, and squeezing out those who are already attending.