Intro and recap

In the first blog in this series, we examined the relative GCSE English and maths attainment of pupils with additional needs – those with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) and those who speak English as an Additional Language (EAL) in 2020 and broke our findings down by ethnicity. In the second blog, we then zoomed in on pupils with SEND and extended our analysis of pandemic GCSE results to show how attainment differed or was similar for pupils of different ethnicities whose schools made additional provision for SEND, and those whose schools did not offer that provision.

The key conclusions we have discussed so far are as follows:

- In 2020, the largest attainment gaps for pupils who speak EAL were similar in size to the largest SEND attainment gaps. Yet there is almost no education policy for children who speak EAL.

- Most ethnic groups among pupils who speak EAL and arrived during Years 7-9 or Years 10-11, had attainment below the national median in GCSE English and maths.

- Pupils with SEND with 6+ years of School Support had similarly low GCSE results to pupils with EHCPs, who receive greater support for their needs and the protection of a statutory plan.

- This suggests that this ‘shadow EHCP’ group of pupils, with 6+ years of School Support but no EHCP, may need better support, particularly at and after the transition to secondary school.

- Our analysis found a range of positive effects for pupils with SEND of attending a school with additional provision. Some of these were more concentrated among ethnic groups with low attainment, making them even more valuable from an equity perspective.

- Effects of additional provision were largest for pupils with EHCPs (with the greatest needs) but remained larger for pupils with 6+ years of School Support than those with 1-5 years of support.

- Resourced Provisions were most associated with better attainment of pupils with 1-5 years of School Support, while both SEN Units and Resourced Provisions were equally associated with positive effects for pupils with 6+ years of School Support. For pupils with EHCPs, SEN Units, but mainly higher ratios of teaching assistants, were associated with better attainment.

- However, benefits of additional provision were not uniformly spread across ethnicities, nor were they always present for low-attaining ethnic groups. Some of the gaps in positive effects may be due to small sample sizes, but this would not account for all the differences observed.

.

This is the nearest we can get to ‘additional provision’ for children who speak EAL because there are no equivalent policies or practices to the SEND register and the SEND Code of Practice, for the EAL group. In the absence of any ‘additional provision’ we explore some visible aspects of school staffing that may possibly be relevant to children’s attainment outcomes. Research has consistently shown that proficiency in English is the key factor that explains low attainment by a subset of children who speak EAL and high attainment by others.

Unfortunately, data are not collected that would pinpoint which school staff do or do not have specific training or experience in teaching children who speak EAL and adapting the curriculum to support their English language development. This is because there are no policies to provide such training and current school accountability measures do not test for this expertise, because of policy neglect in this area. Ideally this would be measurable and enable a more targeted analysis than the one we are able to provide here.

However, our analysis does expose the results of the current laissez-fare approach to the teaching of children who speak EAL, which has been detrimental to EAL attainment. It is clearly not sufficient to hope or assume that suitably expert teachers will appear naturally in schools with the greatest need. This point has often been missed because of the highly variable backgrounds from which children who speak EAL come. For example, a multilingual child whose parents are professionals from the EU is classified as EAL, but so is an unaccompanied asylum-seeking child from Somalia whose prior education has been severely limited.

Analysis in Blog 3

The types of staffing potentially relevant to EAL we will consider are whether or not the school was among those with the most teachers with Black and Minority Ethnic backgrounds (in the top quartile for BME teachers); and whether or not the school was among those with the most teaching assistants (in the top quartile for the ratio of teaching assistants to teachers).

These data are collected in the School Workforce Census and published at school level by the DfE. They may have some potential impact through positive role modelling, but are different from and not a substitute for, specific training in teaching pupils who speak EAL. We have explored the relative absence of systems to support EAL learners in our previous research.

The attainment outcome used in this blog series is GCSE English and mathematics grades, expressed as percentile points in the national distribution. Effects of group membership were initially modelled in comparison with the reference group who were , with no SEND, who do not speak EAL, and have never been eligible for free school meals, since this is the natural comparison group within a regression framework. However, for ease of interpretation given the number of different overlapping group memberships in the analysis, these effects have been translated into comparisons with pupils whose attainment is at the 50th percentile, i.e. those at the median or midpoint of the national attainment distribution. We felt this was an appropriate framing as the school peer group for many pupils includes a variety of ethnic backgrounds, and not just White British pupils.

Longitudinal data on EAL status at the January census each year were used to assign pupils to one of four SEND need categories:

- ‘English First Language’ pupils were never recorded as speaking EAL in any year;

- ‘EAL Arrived by Y7’ pupils were recorded as speaking EAL in at least two years and were found to be enrolled in any state-funded school in England for at least one year between Reception and Year 6, inclusive;

- ‘EAL Arrived Y7-9’ pupils were recorded as speaking EAL in at least two years and were first found to be enrolled in any state-funded school in England between Years 7 and 9, inclusive;

- ‘EAL Arrived Y10-11’ pupils were recorded as speaking EAL in at least one year and were first found to be enrolled in any state-funded school in England in either Year 10 or Year 11.

Staffing in Schools for EAL and Ethnicity

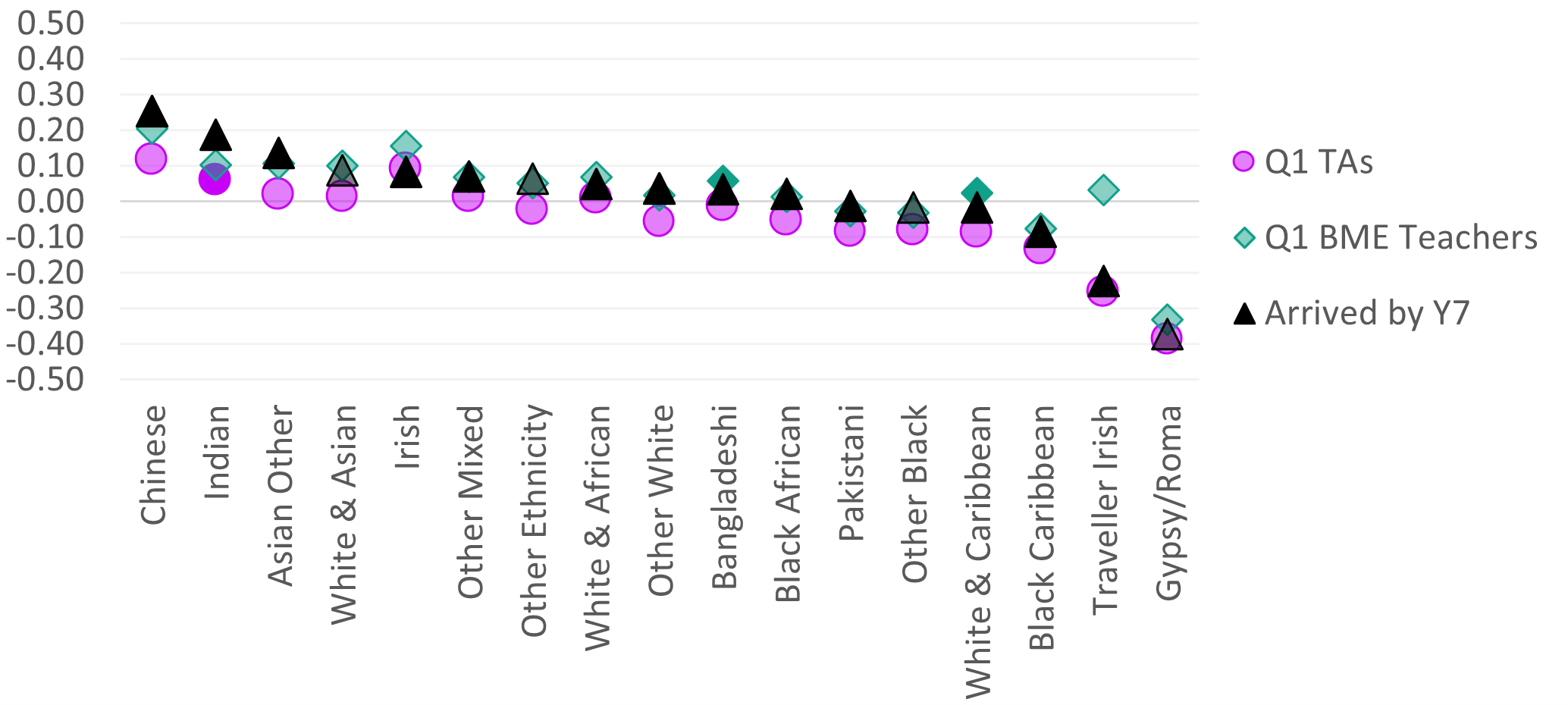

Beginning with pupils who speak EAL and had arrived by Year 7, Figures 1 to 3 present the attainment effects for pupils who speak EAL of attending a school with one of the measured staffing types. The black triangles represent the total group of pupils within each EAL category in each ethnic group. The circles and diamonds represent those pupils within these intersectional groups attending schools with different types of

The measures of staffing for EAL that we were able to construct were blunt. They reflected the overall staffing of the school, rather than provision that was necessarily targeted at pupils who speak EAL. In some cases, pupils attended schools with high quotients of Teaching Assistants, but these may have been deployed primarily towards pupils with SEND rather than those who speak EAL.

In general, we know from our previous research that specialist LA teams have disappeared and there are few if any specialist initial teacher training options for working with children who speak EAL. Indeed, the current Initial Teacher Training and Early Career Frameworks for teachers do not include preparation for teaching children who speak EAL.

Again, when interpreting this analysis, we must be alive to the reality that schools whose pupils have the greatest levels of need are those most likely to have more funding, either through the accumulation of the modest and locally-variable additional per pupil funding for pupils who speak EAL, or through other school funding factors that proxy this, such as deprivation funding and the Pupil Premium, or funding that follows pupils with low prior attainment. This affects the funding available to employ a greater quotient of teaching assistants, in particular.

While funding may be less relevant, on average, the motivation to hire teachers from diverse ethnic backgrounds may also come from a conscious decision to hire teachers that reflect the cultural mix of pupils in a school; or there may simply be more BME teachers available to hire in communities that are more ethnically diverse.

As in blog 2, we will focus on cases where the attainment outcomes are different for pupils of different ethnicities, and refrain from drawing spuriously broad conclusions about the overall effectiveness of one form of provision or another. We describe general differences in attainment by form of provision, but will not draw value judgements from these, and will focus on the relative positions of different ethnic groups. We will not assume that patterns of attainment will be similar in other non-pandemic years and will treat the following analysis as exploratory.

Attainment of pupils who speak EAL and arrived by Year 7

Figure 1: Modelled GCSE Attainment of Pupils who Speak EAL and Arrived by Year 7, by Staffing

Overall, additional provision in the form of staffing variations made little difference to the attainment of pupils who speak EAL and had arrived by Year 7. This is likely to be the result of the resilience in attainment of most ethnic groups, given sufficient time to learn or perfect their English language proficiency, and of the fact that many pupils in this group will have been exposed to English since early childhood or birth, and the majority started school in England in Reception, just like most pupils whose first language was English. This is consistent with earlier research by EPI and others.

Despite the low degree of additional educational need among this group by the time they reached age 16 and were entered for GCSEs, two groups with moderate or low overall attainment did still experience a small but statistically significant positive effect of attending a school with a high quotient of BME teachers. These were:

- White & Caribbean: +2 GCSE percentiles above median, versus -2 percentiles in other schools

- Bangladeshi: +4 GCSE percentiles above median, versus -1 percentile below in other schools

In contrast, Black African pupils who speak EAL and arrived by Year 7 had a very small (-1 percentile, net) but statistically significant negative effect of attending schools with a high quotient of BME teachers. This could easily be a statistical coincidence with no meaning since the more effects one tests for, the more statistically significant results will appear due to chance.

This could also be true of results that seem more intuitive, such as a minority of the results we report showing that additional provision had positive effects for pupils. It’s important not to extrapolate from the results to other pupil cohorts or contexts. They reflect the patterns seen in the 2020 GCSE cohort and may include some anomalies.

While there were no groups with statistically significant positive effects of attending a school with a high quotient of Teaching Assistants, there was one group (Indian) with a statistically significant negative effect. It is not clear why this should be the case, but the effect was equivalent to -13 percentiles (net). It seems there was something distinctive about Indian pupils who speak EAL, arrived by Year 7, reached their GCSEs in 2020, and attended schools with a high quotient of Teaching Assistants, unlike comparable pupils from other ethnic backgrounds. Unfortunately, we cannot identify what was distinctive about this group from the data available to us.

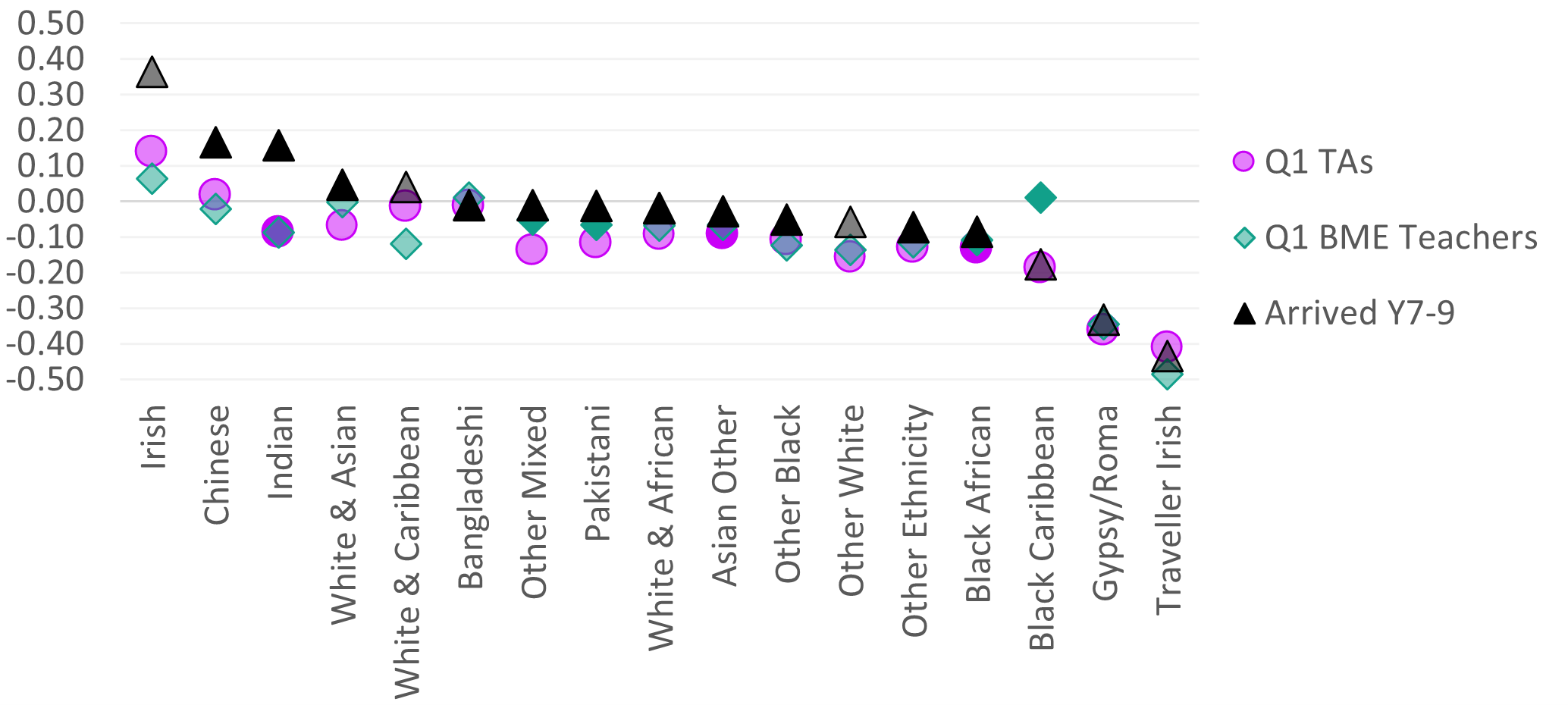

Attainment of pupils who speak EAL and arrived in Years 7-9

Figure 2: Modelled GCSE Attainment, Pupils who Speak EAL and Arrived in Years 7-9, by Staffing

Our analysis of the effects of different staffing models, for pupils who speak EAL and arrived during Years 7-9, reveals only one positive statistically significant effect, although this was a large effect pertaining to a group whose overall attainment is low, making this a tantalising anomaly. This effect was for pupils attending a school with a high quotient of BME teachers:

- Black Caribbean: +1 GCSE percentile above median, versus -18 below in other schools

It may be that this group has distinctive needs for access to role models due to wider experiences of discrimination. Or it may be that this group is more likely to benefit from ethnicity ‘matching’ between teachers and pupils, enabling better bespoke English language support.

However, this effect was not a general one among other groups. We found

Unfortunately, it wasn’t possible to unpick whether ethnicity matching or mismatching between pupils and teachers might partially

In particular, the lack of any policy to provide training or preparation for teaching children who speak EAL, combined with the lack of data about how many teachers have been retained who did receive such training previously, prevents us from understanding the effectiveness of the most obvious policy steps that could be taken (and were previously taken) to support the English proficiency and learning of children who speak EAL.

Similarly, five groups experienced statistically significant negative effects of attending a school with a high quotient of Teaching Assistants. These were Indian (-7 GCSE percentiles, net), Other Asian (-6 percentiles), Other Black (-6 percentiles), Black African (-5 percentiles), and Bangladeshi (negligible < 1 percentile).

Setting aside statistical significance for a moment, the majority of data points in Figure 8 are potentially negative provision effects.

Important context for this finding includes that unlike for SEND, where attainment results remain stubbornly low, but there are statutory duties to support certain pupils, and much education policy debate focused on how things might be improved, there is currently no national policy for supporting pupils who speak EAL beyond a modest funding commitment that we have commented elsewhere does not meet the scale or duration of need, since it is only available for the first three years after arrival.

Specialist support that was built up under the Ethnic Minority Achievement Grant prior to 2011 has greatly eroded over the intervening twelve years and high levels of attrition in the teacher workforce have contributed to the loss of expertise in the school system.

There is no government co-ordinated or mandated EAL training for teachers in supporting children who do not yet have good English proficiency. Neither are there any government-backed or mandated specialist staff roles equivalent to the SENCo (SEND Co-ordinator), although some schools do choose to appoint an ‘EALCO’ on their own initiative.

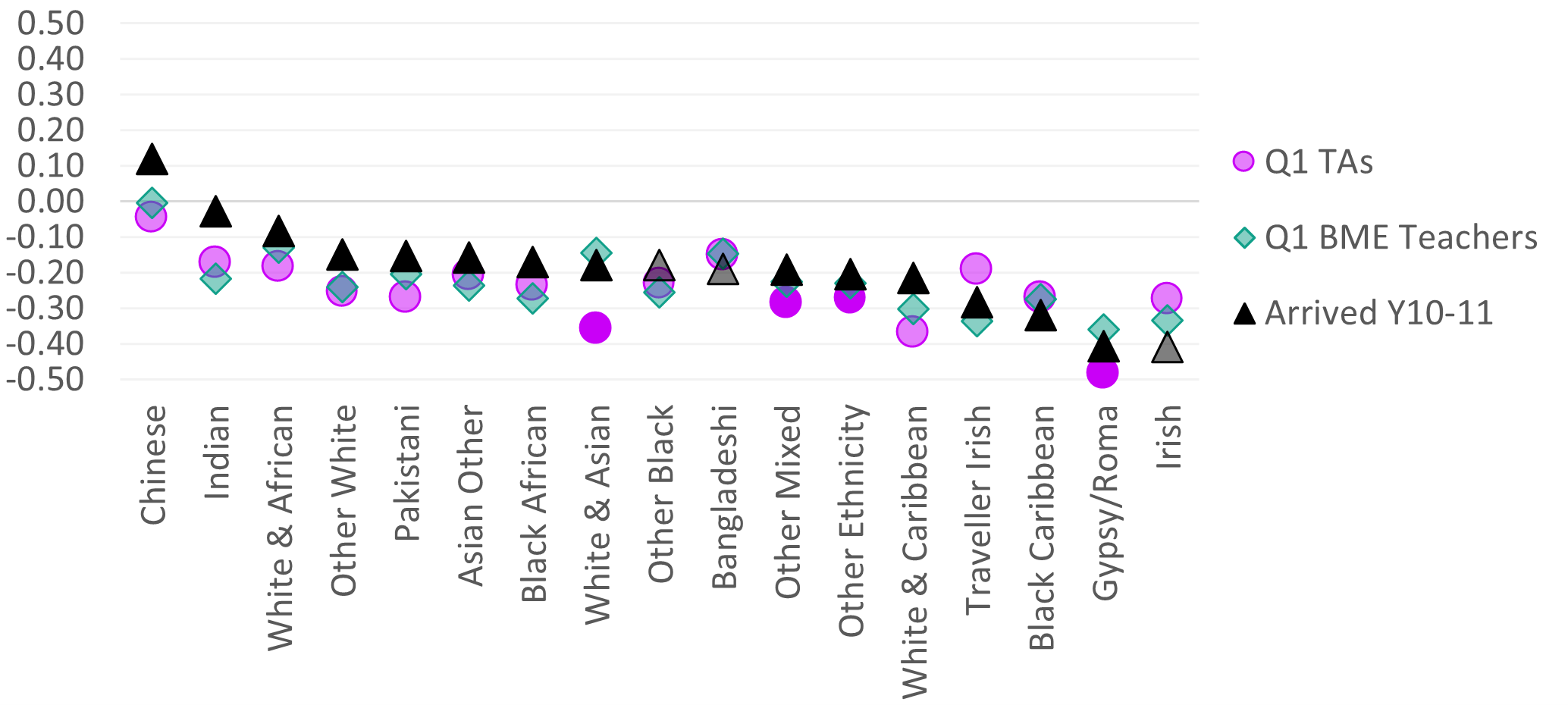

Attainment of late-arriving pupils (Years 10-11) who speak EAL

Turning to the most vulnerable category of EAL need, pupils who speak EAL and arrived during key stage 4, when preparations for GCSEs were underway, Figure 9 reports the attainment effects for different staffing provisions for this group.

Figure 3: Modelled GCSE Attainment of Late-Arriving Pupils who Speak EAL, by Staffing

The picture of attainment for pupils who speak EAL in 2020, as shown by previous research in other years, reaches its most pessimistic for those pupils who were most vulnerable to low attainment because they had little time to settle their lives in England, learn or perfect the English language, learn the curriculum content for GCSEs in English and maths.

And then the pandemic struck, and everyone was additionally challenged by lockdowns and the adoption of technologies for remote learning, where these were even available to pupils before the end of the 2020 academic year. Additionally, there have been new waves of pupil arrivals in schools in England from Afghanistan, Ukraine, and Hong Kong since the onset of the pandemic.

Remote learning, especially when trying to acquire a new language, and especially as some pupils did not initially have access to hardware to make video calls, is likely to have been the straw that broke the camel’s back for this vulnerable subset of EAL-speaking pupils.

All but one ethnic group had attainment below the national median irrespective of staffing provisions, and there were no positive effects of access to either in terms of schools with a high quotient of BME teachers, or in terms of schools with a high quotient of Teaching Assistants.

As discussed earlier, this is not terribly surprising given that specialist expertise in teaching children who speak EAL is needed, particularly to support those who arrive during Key Stage 4, but is insufficiently available, and not measured in the data collected in the School Workforce Census.

There were no statistically significant effects of attending a school with a high quotient of BME teachers for this most vulnerable subset of EAL-speakers, either positive or negative. However, four groups experienced negative effects of attending schools with high quotients of Teaching Assistants. This is likely to be at least partly explained by insufficient access to those TAs for pupils who speak EAL and/or insufficient training of TAs to support the learning of pupils who speak EAL. The four groups with negative effects were:

- White & Asian: -36 GCSE percentiles below median, versus -18 in other schools

- Other Mixed: -28 GCSE percentiles below median, versus -19 in other schools

- Other Ethnicity: -27 GCSE percentiles below median, versus -20 in other schools

- Gypsy Roma: -48 GCSE percentiles below median, versus -41 in other schools

We can’t tell from the analysis exactly why this is the case. It’s possible it might be a story about and who and where the pandemic struck hardest at the 2020 GCSE cohort in terms of pupils and staff becoming ill and missing school time, in addition to the lack of appropriately trained specialist support targeted at pupils who speak EAL. Or it might reflect other more long-standing vulnerabilities that explain why those schools hired additional Teaching Assistants to begin with. The data can only tell us so much and our analysis doesn’t answer this question.

Conclusions on the Attainment of Pupils with SEND in 2020

Our analysis found that, at least in 2020, most ethnic groups of pupils who speak EAL and arrived during Years 7-9 and all but one ethnic group among late-arrivals in Years 10-11, had attainment below the national median in the core GCSE subjects of English and maths.

We know from previous research that some portion of this low attainment was ‘additional’ or specific to 2020 and the pandemic onset that saw schools adopt remote learning for most pupils and the submission of centre assessed GCSE grades to awarding bodies, based on the written work that pupils had undertaken, rather than on examinations as is normally the case.

Very few positive effects of additional staffing provision were found for pupils who speak EAL (three in total across 102 groups of pupils tested), and these were exclusive to groups who arrived in their first state school in England before the start of key stage 4 in Year 10. This is unsurprising given that the specialist support needed for developing proficiency in English is not available in most cases, and therefore any positive impact of role modelling is undermined.

Positive effects of provision were further limited to schools with a high quotient of BME teachers and were not found for any groups of pupils attending schools with a high quotient of Teaching Assistants.

It is possible that some or all of these positive effects were due to chance, although the largest effect for Black Caribbean pupils who arrived in Years 7-9 (+19 GCSE percentiles, net) shows some potential to be due to ‘ethnicity matching’ between pupils and teachers and particular vulnerability of this ethnic group.

In addition to these potential positive effects of additional provision for pupils who speak EAL, there were a much larger number of negative statistically significant provision effects (fifteen) spread across all EAL categories and for high quotients of both Teaching Assistants and BME teachers.

It’s possible these reflected the unequal impact of pandemic illness burdens in 2020, or that staff in some schools with high needs across SEND, EAL, mental health and social care were distracted with other priorities at the expense of EAL-speaking pupils, impacting unevenly across ethnic groups.

With hindsight, it is likely unrealistic to expect schools to have found solutions to this perfect storm of events, without any specific support from the government on EAL. This is not a reflection on schools, on teachers, or on particular staffing models, so much as it is a sad story about how no solution was forthcoming for this group of pupils, even in schools with more resources to deploy.

It’s not surprising that the legacy of over a decade with no government support to ensure that children who speak EAL are taught by teachers and TAs with specialist training is visible in their GCSE results, in 2020 as in earlier years.

Indeed, funding alone would not fix every problem because it cannot turn back the clocks for a group who did not experience the ‘normal’ path to GCSEs, twice over, by having an education interrupted by migration, and by having their GCSEs interrupted by a global pandemic.

This doesn’t mean that nothing can be done for pupils who speak EAL and are still in school, however. Specialist teacher training and the development of English proficiency within the existing school curriculum through adaptive teaching methods are promising policies that could be introduced to improve attainment outcomes for late-arriving pupils who speak EAL. The routine assessment of English language proficiency for pupils who speak EAL to support this specialist teaching could be re-introduced.

The largest attainment gaps for pupils who speak EAL were of similar size to the largest SEND attainment gaps. Yet there is a vast discrepancy in the amount of policy attention towards SEND and EAL. While there are many long-standing problems in SEND policy that are worthy of ongoing attention, there at least is a SEND policy.