Summary

- Resits are important – lots of students do not achieve a good GCSE pass in English and maths at 16, they are a big focus of upcoming policy changes and literacy and numeracy skills have big impacts on life chances.

- However, grade improvements and pass rates for those who resit are very low.

- Results are even worse for disadvantaged students and those with special educational needs.

- Outcomes are significantly worse for GCSEs than other qualifications and disadvantage gaps have been growing over time.

- In the current policy environment, there is a significant opportunity to develop a much better offer for students.

Overview

When a student falls short of a good pass (grade 4) in their GCSE English and maths at age 16, they have to continue studying English and maths in their 16 to 18 education. This is part of the resit policy introduced in 2014, known formally as the condition of funding requirements.1 In practice, these students will also face barriers in terms of access to apprenticeships and more challenging level three qualifications including T levels and A levels. The current government plans to replace these qualifications with the recently announced Advanced British Standard (ABS) – an all-encompassing baccalaureate-style qualification for 16 to 19-year-olds.2 The ABS places great emphasis on strengthening English and maths education, with all students required to take these subjects until they are 18. However, there are still questions about the programmes of study current “resit” students will take under the ABS.

Recent statistics from the Department for Education (DfE) show resitting English and maths is the reality for a significant proportion of students. In 2022/23, almost 40 per cent of students did not achieve a good pass in their English and maths GCSE at 16. With GCSE standards now back at pre-pandemic levels, it is likely even more students will be affected by the resit policy over the next few years.

Despite the number of students affected by the resit policy and the strong emphasis on English and maths in the ABS proposals, we still have many unknowns regarding the effectiveness of the resit policy in improving outcomes for young people and addressing inequalities.

Why do we need a better understanding of the impact of resits?

Firstly, literacy and numeracy skills have major influences on important life outcomes like wages, health, life satisfaction, and civic engagement.3,4 As such, it is crucial to provide all students with the opportunity to attain a good core knowledge in these areas. This is one of the driving forces behind the resit policy and the English and maths component of the ABS.

Secondly, disadvantaged students and those with special educational needs (SEN) are more likely to fall within the resit group.5 If the resit policy isn’t working well and progress in English and maths is low, we risk widening disadvantage gaps and inequality even further.

Thirdly, the government wants to funnel more money into resit students in preparation for the ABS.2 They plan on doing this by increasing the funding rates for level 2 English and maths during post-16 study. It is thus important to understand how the resit policy is performing to better target this increase in funding.

Finally, under the ABS, all students will be studying English and maths until they are 18. Under the current proposal, students without a good pass in GCSE English and maths at 16 would take an ABS level 2 minor in English and maths.6 What is still up for debate, however, is how similar that minor will be to existing GCSEs and Functional Skills Qualifications (FSQs) and what the course will and will not include. It is important that this programme of study is well-designed and thought out so that students studying at level 2 don’t fall even further behind their peers who are studying English and maths at Level 3 under the ABS. With the ABS discussions, there is a real opportunity to develop ambitious new study programmes for current resit students. But this first requires an understanding of how the resit policy is impacting students.

This blog explores the entries, results, and progress of resit students, shedding light on this important topic.

What English and maths courses are resit students taking?

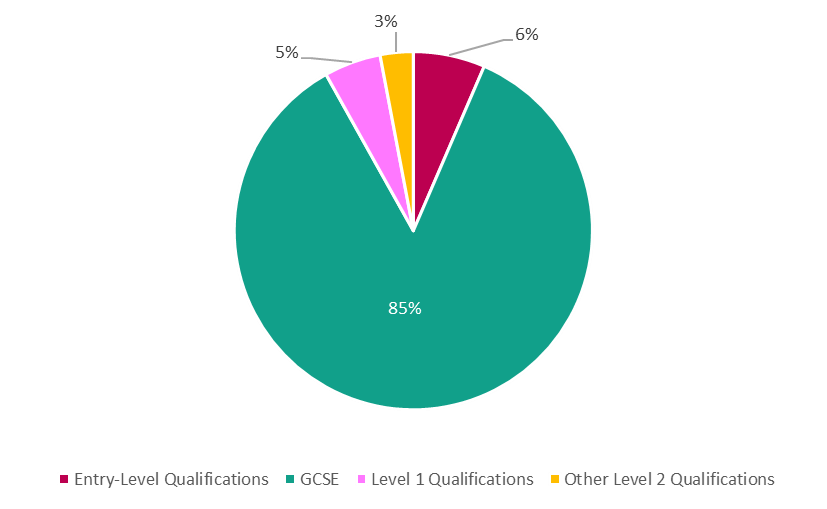

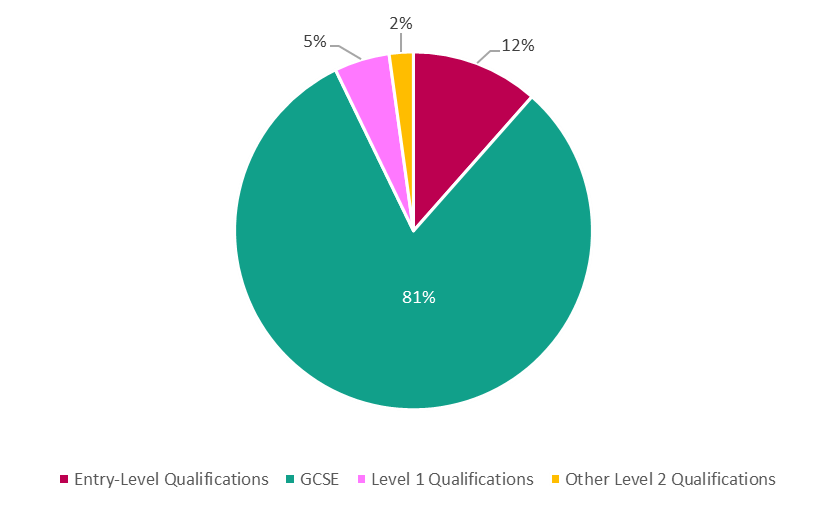

In 16 to 18 entry and attainment data recently released by DfE (2023), we see that over four in five resit entries were in GCSEs.7 Non-GCSE entries are split between other level 2 courses, level 1 courses and entry-level courses, most of which are FSQs (see Figures 1 and 2). There are over 28 times more entries in GCSE English than other level 2 qualifications and there are over 37 times more entries in GCSE maths than other level 2 qualifications. And remarkably, in general, entries into different qualifications depend little on student characteristics (like disadvantaged status).

Under the resit policy, if students achieve a grade 3 (or D, under the old grading system) they must continue to study GCSEs. Students lower than a grade 3 can take other courses at level 2 or below (this allowance was introduced in 2019/20). This partially explains the large proportion of students who entered into GCSEs. However, over the past few years, the proportion of resit students who had achieved a grade 3 was approximately the same as the proportion of resit students who achieved below a grade 3.8 This means that a considerable group of students are entered into GCSEs, instead of other qualifications, despite falling short of their GCSEs at 16 by at least two grade boundaries.

Previous researchers have documented the prevalence of school sixth forms and colleges entering resit students on to GCSEs, despite those students achieving below a grade 3 at key stage 4 (KS4).9,10 They show that there has been a trend towards GCSEs rather than FSQs for resit students and that some colleges apply a blanket approach where all resit students are entered onto GCSEs, regardless of prior attainment.10,11 This may, in part, be because a GCSE qualification has greater currency with parents, employers, students and other stakeholders.9,11,12 It could also be because entering students into GCSEs provides more funding than FSQs in some cases (because GCSEs have more planned hours). Others have also argued that colleges have an incentive to enrol students on GCSEs because they can help deliver higher progress scores for the college (GCSEs are worth more than FSQs).10 But this all risks creating a demoralising culture of failure where students keep failing GCSE resits because they aren’t entered onto an appropriate course.

Figure 1. 2022/23 below level 3 16 to 18 English enrolments

Source: DfE (2023).7

Figure 2. 2022/23 below level 3 16 to 18 maths enrolments

Source: DfE (2023).7

How do students get on in their resits?

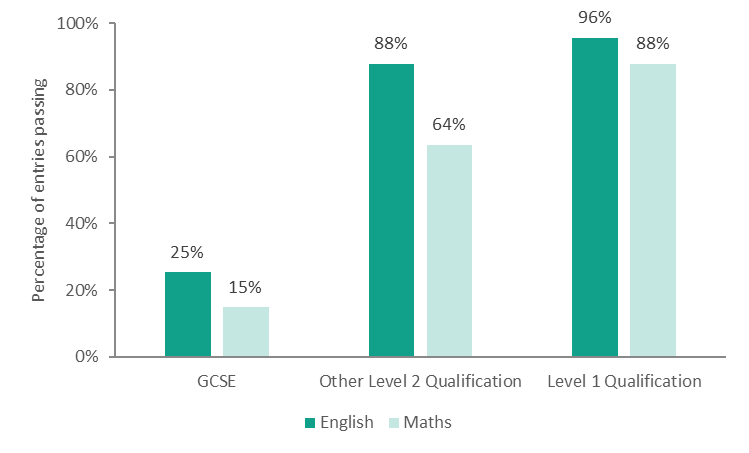

In Figure 3, we show the pass rates for resit entries in 2022/23 by qualification type (GCSE, other level 2 qualifications, and level 1 qualifications). This is a snapshot of the performance of all 16 to 18 resit students in 2022/23. We do not show results for entry-level qualifications because the pass rate was 100 per cent in 2022/23 and did not vary by subject or student characteristics.

Overall, for GCSEs, the pass rate was very low. On average, less than a quarter of students passed their GCSE entry whereas around three quarters passed their other level 2 qualifications and over nine in ten students passed their level 1 entries. Pass rates for maths were significantly lower than they were for English.

Figure 3. 2022/23 English and maths resit pass rates by qualification type

Source: DfE (2023).7

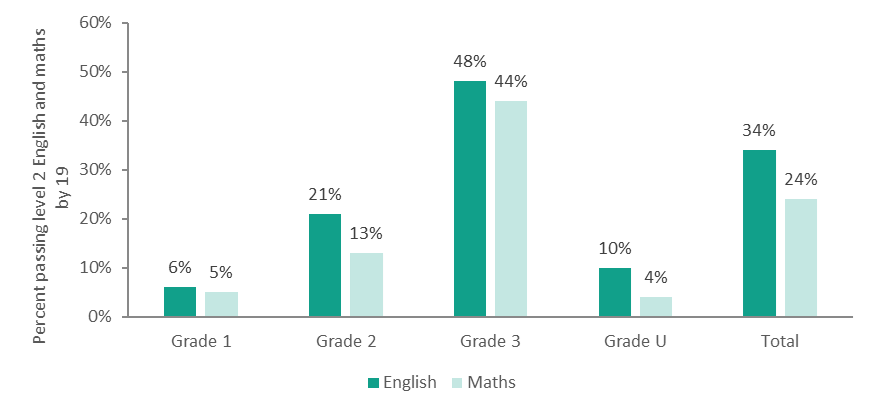

Looking at progress during a student’s entire 16 to 19 education, Figure 4 shows that most students did not achieve level 2 English and maths by 19 if they had not done so at 16. Only a third of students progress and pass English by 19 and less than a quarter pass maths by 19. However, those with higher GCSE prior attainment are more likely to pass level 2 English and maths by 19. Just under half of students with a grade 3 at 16 pass level 2 English and maths by 19. On the other hand, around one in twenty students with a grade 1 or U do so in maths (slightly more students pass English). The low progress rates for those with grades 2 or lower are likely driven by the low pass rates for GCSE English and maths (Figure 3), which most students are enrolled in (Figures 1 and 2). The progress results in Figure 4 are for 2018/19 because the results for all available later years are influenced by pandemic grading.

Figure 4. Percentage of students achieving level 2 English and maths by 19 who had not done so by 16 for 2018/19 by original GCSE grade at 16

Source: DFE (2020).13

Resit results over time

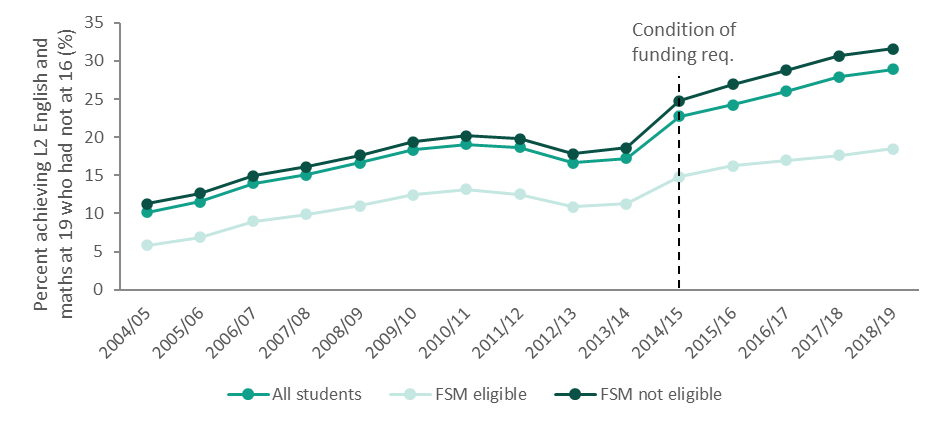

The rate of progress has been increasing slowly over time (Figure 5). However, the progress rate in 2018/19 was still very low, with less than a third of students progressing to level 2 English and maths by 19. Furthermore, while progress rates have been increasing since the resit policy was introduced, the gap between disadvantaged (those with free school meal eligibility) and non-disadvantaged students has widened. Disadvantaged students are over-represented in the resit cohort, making up 39 per cent of all below level 3 English and maths entries in 2022/23 compared with 23 per cent of the cohort as a whole

Figure 5. Percentage of students achieving both level 2 English and maths by 19 who had not done so by 16 over time.

Source: DFE (2020).13

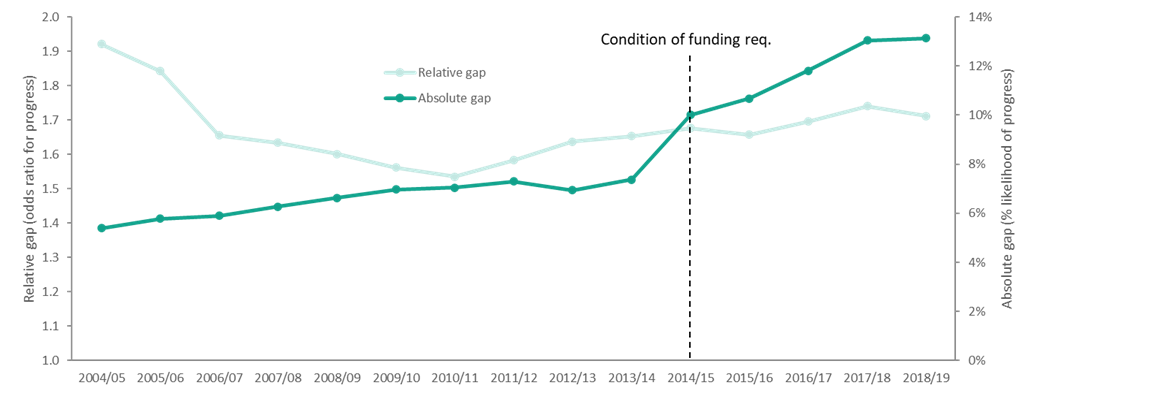

Figure 6 shows the absolute and relative gaps in level 2 English and maths progression between FSM eligible students and non-FSM eligible students. The absolute gap is the percentage point difference between non-FSM and FSM students’ progress rates and the relative gap, or odds ratio, measures how much more likely non-FSM students are to progress (non-FSM progress rate/FSM progress rate).

The absolute gap has been increasing over time and appears to have accelerated since the condition of funding requirements were introduced. On the other hand, the relative gap fell between 2004/05 and 2010/11 and has been slowly rising since. The relative gap was around 70 per cent in 2018/19, indicating that non-FSM eligible students are 70 per cent more likely to progress than FSM eligible students. This relative gap has been constant since the resit policy was introduced.

Worryingly, the increase in the absolute disadvantage gap for resit students prior to the pandemic has occurred against the backdrop of a narrowing gap in other parts of the education system.14 This suggests efforts to reduce disadvantage gaps were systematically missing English and maths attainment for resit students.

Figure 6. Disadvantage gap in 16 to 19 progression for level 2 English and maths for FSM eligible students.

Source: DFE (2020).13

Progress by student characteristics

In the following graphs, we break down resit pass rates and progress by student characteristics. Figure 7 shows how 2022/23 resit pass rates vary according to a range of student characteristics and Figure 8 shows how pass rates vary by student ethnicity. These two graphs look specifically at GCSE pass rates, given they are what most students are enrolled in.

Disadvantaged students are around a third less likely to pass than resit students on average. Students with SEN support are around 40 per cent less likely to pass English and maths whilst students with EHC plans are 40 per cent and 28 per cent less likely to pass English and maths, respectively. This is concerning, given a disproportionately large number of disadvantaged students and students with SEN end up in the resit cohort (for example, in 2022/23, disadvantaged students made up 39 per cent of resit entries but only represented 26 per cent of total students). However, it is worth noting that some students with SEN are exempt from the resit policy and thus won’t be included in the results shown in this blog. Males tend to pass more often than females in maths, and females pass more often than males in English. Those with English as their first language pass less often than other students in both English and maths.

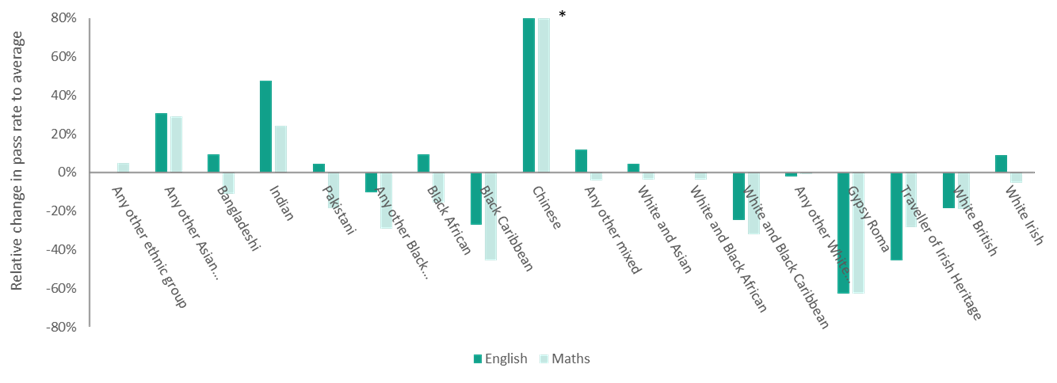

There is wide variation in GCSE resit pass rates by ethnicity (Figure 8). Chinese students perform significantly better than all other students in both English and maths and are less likely to be in the resit cohort in the first place. Chinese students are almost five times more likely to pass maths and more than twice as likely to pass English than the average student (the bars for Chinese students are truncated in Figure 8). Asian or Asian British students (including Bangladeshi, Indian and Pakistani students) are more likely to pass their resits than the average student. However, Pakistani and Bangladeshi students are slightly less likely to pass maths. In general, both Black and White students are less likely to pass English and maths than other students on average. Black Caribbean students, Travellers of Irish heritage and Gypsy Roma students tend to have the lowest relative pass rates (between 25 and 65 per cent less likely to pass than the average student).

Figure 7. Pass rates for GCSE English and maths in 2022/23 by student characteristics. All values are relative to the average pass probability for that course.

Source: DfE (2023).7

Figure 8. Pass rates for GCSE English and maths in 2022/23 by student ethnicity.

Source: DfE (2023).7

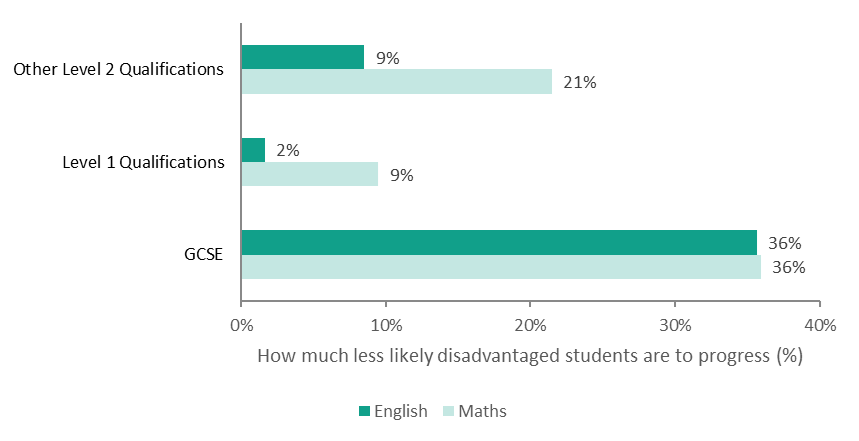

The patterns observed for other qualifications are similar to those observed for GCSEs. However, the size of the gaps between different student groups appears to be largest for GCSEs. In Figure 9, we show the disadvantage gap by qualification type. The gap is how much less likely disadvantaged students are to pass than non-disadvantaged students. The gap is very large for GCSEs (as shown above), with the pass rate being 36 per cent lower for disadvantaged students. The gap is still relatively large for other level 2 math qualifications, with the pass rate being 22 per cent lower on average. The gap is 9 per cent for other level 2 English qualifications. The gap becomes even smaller for level 1 qualifications (it is very close to zero for level 1 English qualifications).

Figure 9 shows that success in other qualifications (mainly FSQs) is less dependent on student characteristics than in GCSEs. Moreover, for other qualifications, gaps in English are smaller than those in maths. The consistently wide gap in maths achievement has likely contributed to the growing attention on reforming and improving mathematics provision in the 16-19 phase.11,12

Figure 9. Disadvantage gap by qualification type.

Source: DfE (2023).7

Some students get lower grades when resitting

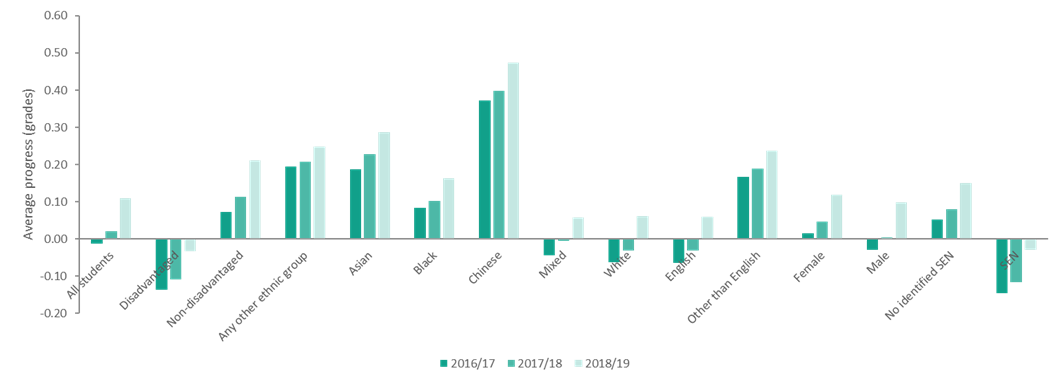

Between 2016/17 and 2018/19 (prior to pandemic grading), DfE published results for a measure called average progress (this measure will likely be published again in 2024). Rather than a simple pass or fail metric, the average progress measure subtracts the performance at the end of KS4 from the best performance in English or maths during the post-16 phase. This gives a measure of overall progress and allows us to compare original and resit grades. A one unit increase in the scale roughly approximates to a one grade improvement (i.e., a D to a C or a 3 to a 4) in GCSEs.15

In Figure 10, we show average progress scores for different groups for the years 2016/17, 2017/18 and 2018/19. There was a general upwards trend over time during these periods, consistent with our earlier graphs (Figure 5). However, the overall progress scores are shockingly low. Overall, in 2018/19 average progress was only 0.11 and very close to zero in the previous two years. This means, on average, resit students only improve their English and maths scores by just over one tenth of a grade.

Like before, we also see wide variation in average progress across student groups, and that some groups have negative progress overall (though, note that students receiving lower grades in their resits can still list their original grades on applications etc.). In particular, disadvantaged students and students with SEN seem to go ‘backwards’ or make no progress at all on average (the average progress score for both of these groups in 2018/19 was -0.03). Scores for these groups improved in 2018/19 compared with 2016/17 and 2017/18, where average progress was well under zero (between -0.11 and -0.15 for disadvantaged students and students with SEN).

White students and – students whose first language is English also seem to make very little progress, with average progress scores of 0.06 in 2018/19. This is consistently lower than the average resit student. On the other hand, Chinese and Asian students make above average progress, with Chinese students progressing 0.47 grades on average – approximately eight times the size of the average progress made by white and mixed ethnicity students. Black students make more than double the amount of progress as white students, with an average progress score of 0.16. Unlike the 2022/23 pass rates for GCSEs, Black students perform better than the average resit student and this may be because Black students perform better on other English and maths qualifications.

Figure 10. Average progress scores in between 2016/17 and 2018/19 by student characteristics (DfE, 2020)13.

Source: DfE (2020).13

Conclusion – the resit policy is struggling

Given the importance of English and maths for long-term life outcomes and the importance of increasing attainment for those in the resit cohort ahead of policy proposals like the ABS, this analysis has examined the progress of resit students.

In 2022/23, an overwhelming majority of resit students were entered into GCSEs, as opposed to other level 2 qualifications (or lower-level qualifications). This applies even for students who fall at least two grades below the passing grade in their GCSEs at 16. This is driven by a myriad of factors, including that GCSEs have greater recognition by stakeholders, there are staff shortages (particularly for maths) and criticisms around the reformed FSQs. These enrolment decisions may also, at least in part, be driven by decisions around funding (GCSEs are longer courses so will bump students into higher funding bands in some instances). Others have also suggested that colleges have an incentive to enrol students in GCSEs to try and maximise their progress scores (used by Ofsted).10

Irrespective of the reason, we show that enrolling in and resitting GCSEs is not working for most students, whilst pass rates are higher in alternative English and maths courses such as FSQs. Moreover, disadvantaged students are less likely to pass GCSE English and maths than their non-disadvantaged peers, whereas gaps are smaller in alternative qualifications.

When we look at English and maths progress, we see similar trends of extremely low achievement and large disadvantage and SEN gaps. Under the average progress measure, disadvantaged students and students with SEN appear to be going backwards under the resit policy. Moreover, disadvantage gaps for resit students have been widening over time which is concerning given disadvantaged students are more likely to end up doing resits.

The analysis here is limited by the aggregated nature of the data that is publicly available. However, at a high level, these results point to some real areas of concern. Taken together, the results here indicate that the resit policy is not increasing the numeracy or literacy of most students and particularly our most vulnerable learners.

There is a need for a much better understanding of the resit cohort and how their learning evolves during the 16 to 19 phase. For example, how does progress vary by course characteristics and how much of the results here are down to a lack of engagement with mandatory courses? And what happens to resit students after they finish their post-16 education? These questions are increasingly important in the current policy environment where there is a growing focus on improving post-16 English and maths results.

Outlook

In their ABS consultation document, the government has signalled that they want to develop a much stronger offer for students studying English and maths below level 3.6 They plan to introduce new high-quality level 2 English and maths “minors” but have not yet set out what these programmes of study will look like. The government is consulting on how much current FSQs and GCSEs should feed into these new programmes of study. This presents a significant opportunity to develop ambitious and innovative offerings for resit students.

Sector bodies, colleges, students and politicians have criticised both GCSEs and FSQs for their ability to develop literacy and numeracy skills. In the context of the ABS, there is a real opportunity to develop new English and maths programmes that focus on developing the core literacy and numeracy skills young people need to actively participate in society. This could involve taking pieces both from current GCSEs and FSQs, as well as weaving in new material and teaching methods that most suit the students who will be taking such programmes.

There is also a significant opportunity to design these level 2 English and maths programmes in a way that avoids the stigma issues associated with less academic/more functional alternatives to GCSEs. We know that many students take GCSEs because they are better recognised and hold greater value with various stakeholders, including parents and employers. This has led to calls for alternative post-16 GCSEs that are specifically tailored to resit students and adult learners and retain the GCSE title.11,12,16,17 A similar principle could be adopted for the ABS, with the development of two paths for level 2 English and maths under one overarching programme. For example, an ABS minor in maths and an ABS minor in maths (occupational). This would allow students to take a programme of study that best aligns with their needs and aspirations, whilst worrying less about the qualification’s reputation. For example, students could take the occupational minor and have their study focused more on core skills for work and life and less on theoretical and abstract concepts. Likewise, students could take the more academic minor which includes more theoretical content to prepare students for further study in these subjects.

We are at a crossroads and the ABS and surrounding policy discussions offer us a chance to provide much greater opportunities to resit students. Opportunities that could genuinely improve their future career trajectories and ability to contribute to society. The current consultation document outlines the bones of a new way forward. However, the ABS is a highly ambitious proposal and English and maths provision for resit students is just one part of that. Making up just two of 58 consultation questions, there is a risk that developing a better offer for resit students falls down the priority list. Not to mention, with the upcoming general election, it is unclear whether these reforms will ever take place.

But we cannot let the opportunity to improve things slip. The resit policy isn’t working for most students. The time is now to re-think and radically transform our offering to resit students so that everyone can secure basic numeracy and literacy skills.