The Department for Education last week released its annual snapshot of the state of the teaching workforce in England and it is sober reading for the incoming government. Last year’s statistics showed the recruitment and retention boost of the pandemic to be just that: a blip. The latest figures show that the growth in the workforce is still being outpaced by the growth in pupil numbers. The number of teachers in primary schools fell, while the number of teachers in secondary schools grew more slowly than the number of pupils, so pupil-teacher ratios continue to rise in both primary and secondary schools.

Nonetheless, there are glimmers of hope. The retention of early-career teachers has continued to improve since last year, which may be related to improvements the government has made in the support for new teachers, and the number of teachers returning to the profession has also risen despite the public tensions over teachers’ pay and conditions. It is unclear why more teachers are returning to the profession, even as more are leaving it, but it may give the next government some hope that it can turn the tide on the long-running recruitment and retention problems.

Below we set out seven charts that show the key trends in the data.

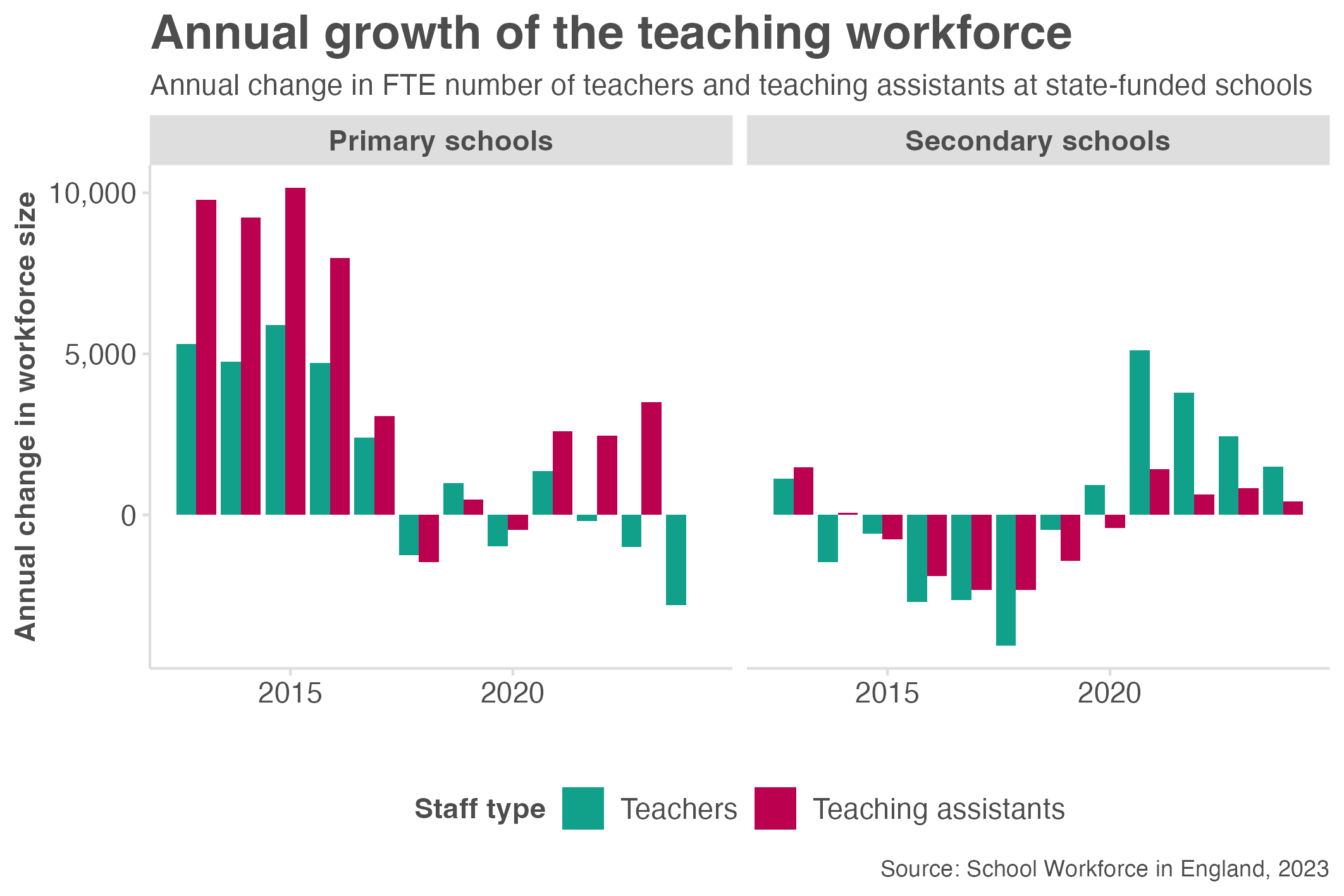

1. The growth in the number of teachers has stalled…

The first chart shows that, while the school workforce has grown slightly between 2022/23 and 2023/24, most of that growth is in primary school teaching assistants. The number of teaching assistants has grown by 0.6 per cent, while the number of teachers has grown by less than 0.1 per cent overall and has fallen in primary schools. The number of teaching assistants in schools is now the highest on record and is up 28 per cent since 2011/12.

Schools are understandably using teaching assistants to compensate for the difficulty they have in recruiting teachers, but it is possible that the quality of children’s education will suffer as a consequence. Teaching assistants are not qualified teachers and, while they can be a valuable resource in the classroom, they are not a substitute for an expert teacher.

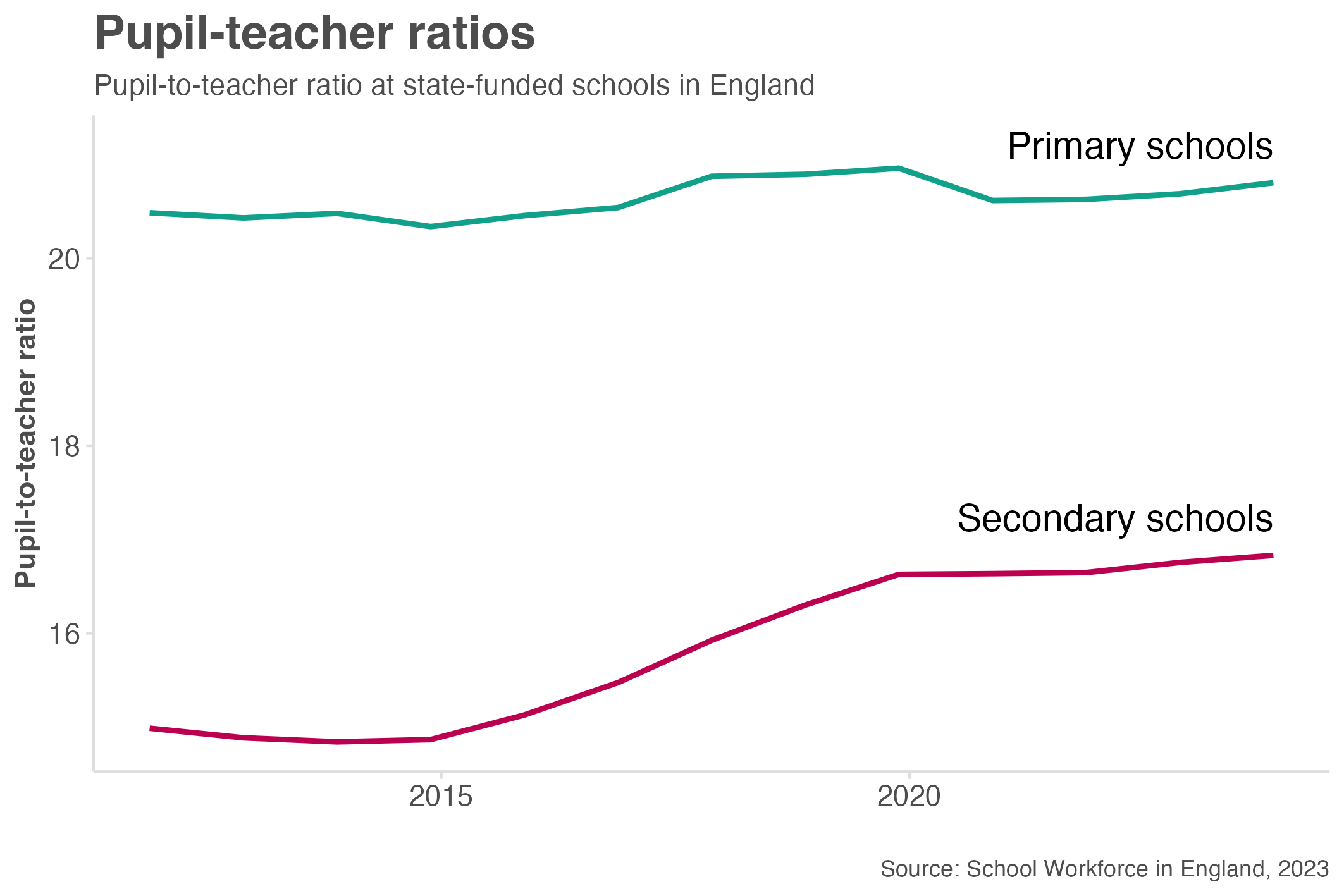

2…and pupil-teacher ratios continue to grow

There has been a surge in pupil numbers in recent years that has passed through primary schools and is now passing through secondary schools. However, in both settings, recruitment and retention efforts remain behind the curve. The number of teachers in primary schools is falling faster than pupil numbers while the number of teachers in secondary schools is growing more slowly than pupil numbers. The result is that pupil-teacher ratios are rising in both primary and secondary schools. In secondary schools the pupil-teacher ratio is now about 14 per cent higher than it was in 2012/13 (1).

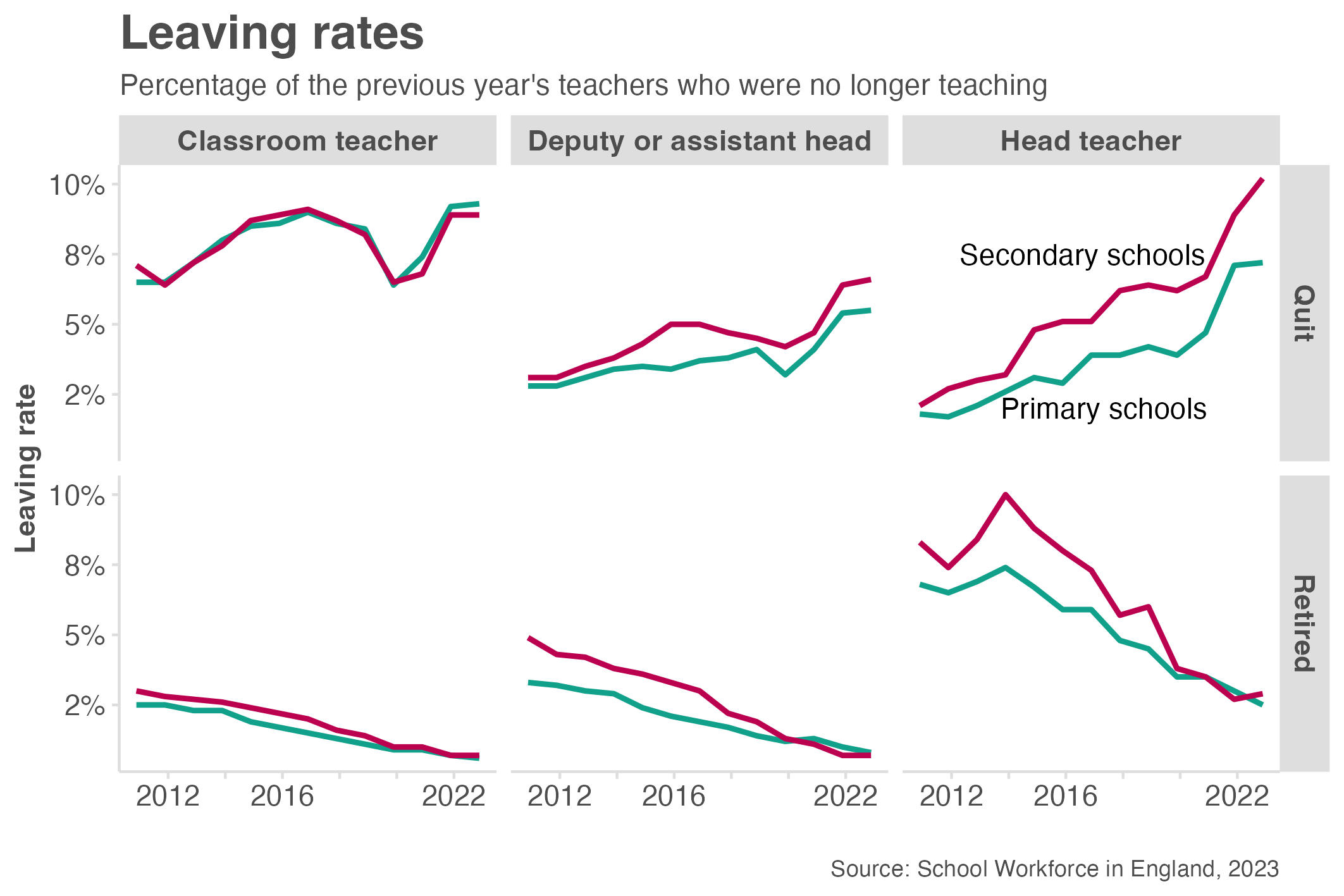

3. Headteachers are quitting the profession earlier…

Last year’s surge in teachers leaving the profession early has not worsened but nor has it improved. The trend of teachers leaving the profession before retirement age has continued and it has grown particularly among secondary headteachers. These heads are now over five times as likely to quit the profession before retirement as they were in 2010/11.

The loss of experienced headteachers is not just a problem for the schools they leave but for the whole education system. Headteachers improve with experience and a newly promoted head is not a substitute for one with a decade’s experience.

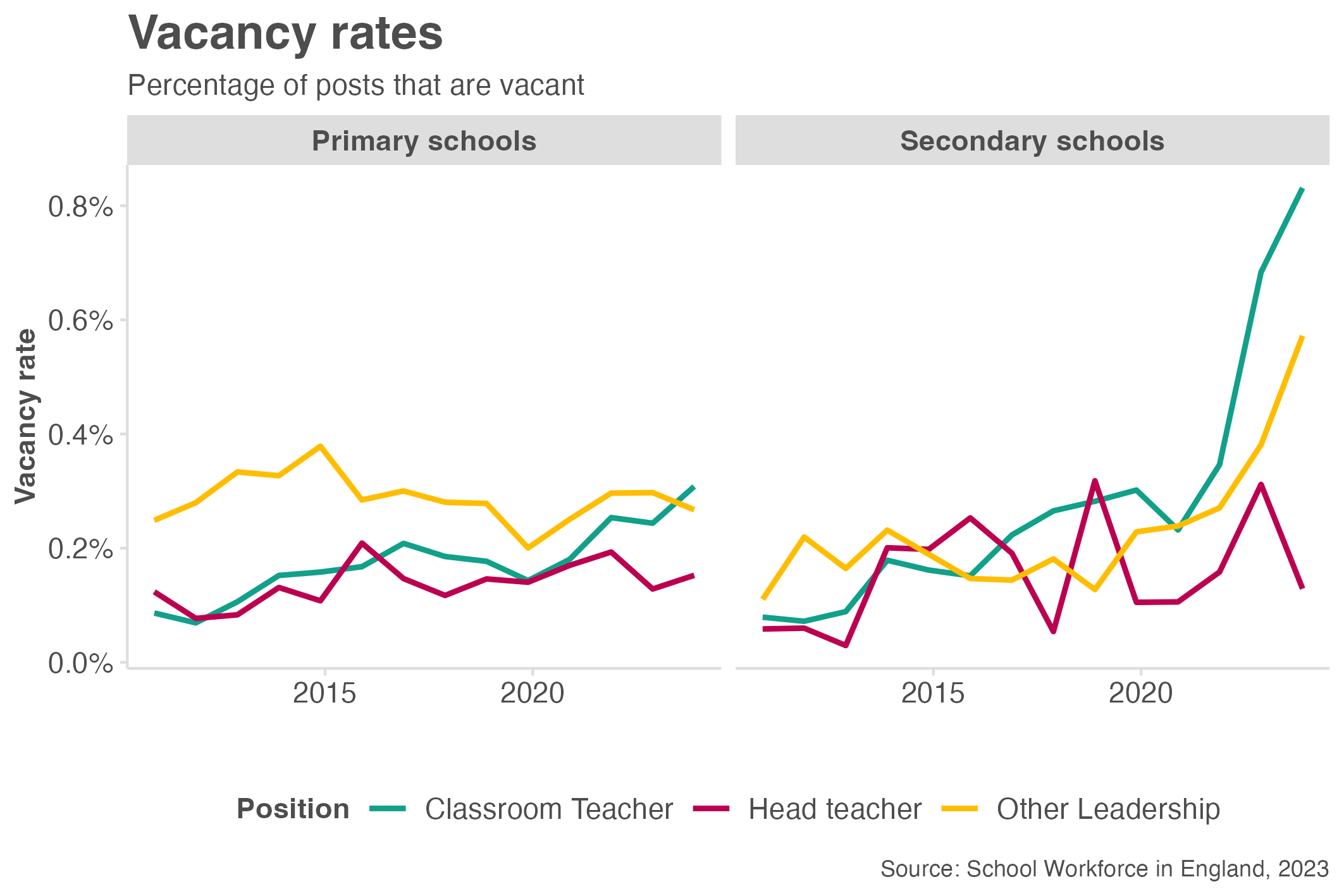

4…and there are a record number of vacancies for secondary teachers

The number of vacancies for secondary classroom teachers has reached a record high, with nearly one per cent of posts vacant in November 2023. More than any other statistic, this shows the tremendous difficulties secondary schools have had recruiting teachers. The pressure this places on school leaders is immense, and it is no surprise that headteachers are quitting the profession earlier than ever.

5. Retention rates are still falling…

Overall retention rates have fallen slightly again but there may be a silver lining in the retention of early career teachers. The retention of teachers one year past qualification has improved to the highest level in the last 13 years. This is a positive sign that the government’s efforts to improve the support for new teachers through the early career framework might be having an effect. The government recently published a review of the early career framework and an incoming administration should aim to learn from that to build on the success so far.

6.…but more teachers returned to the profession…

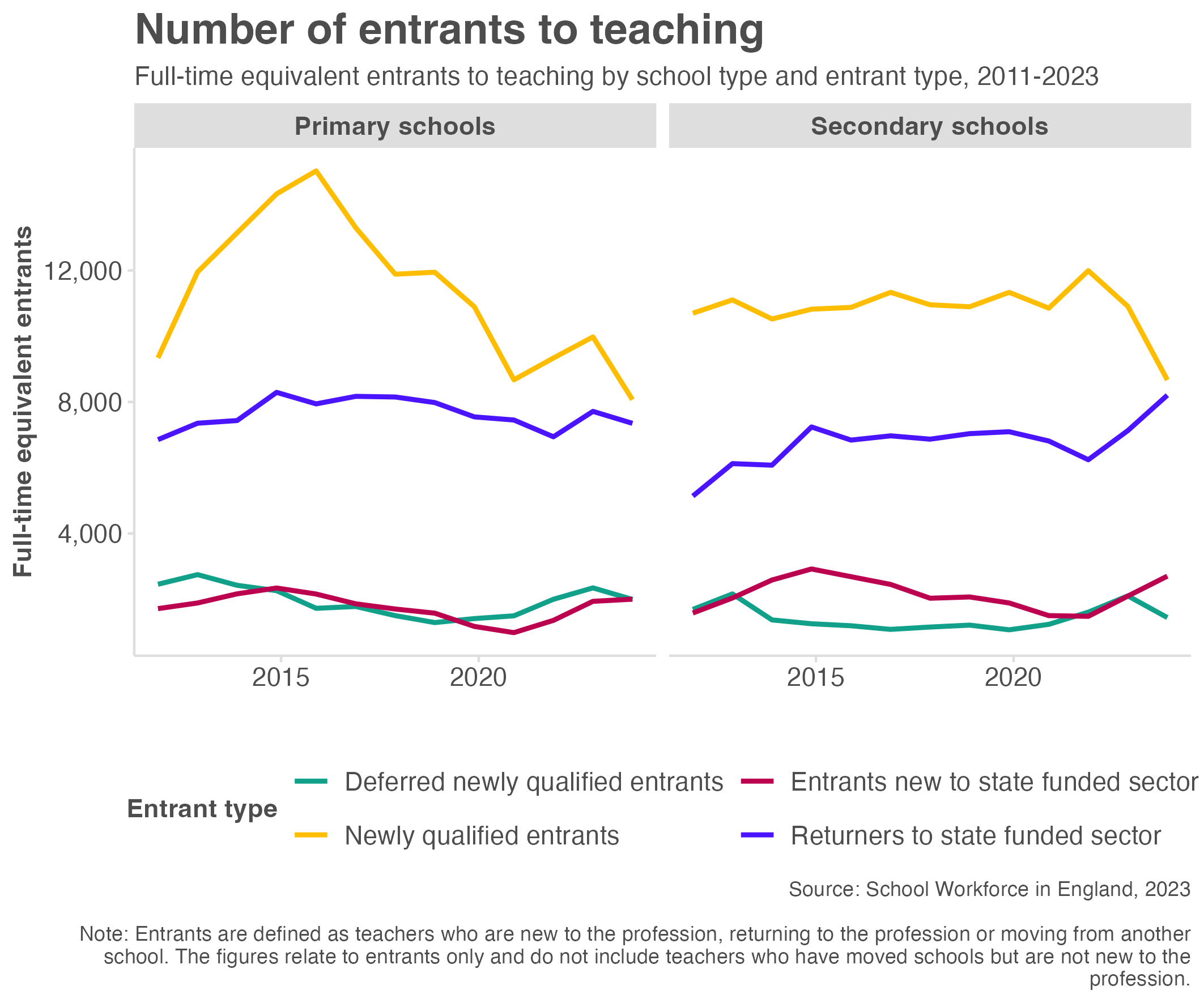

Perhaps the most surprising statistic in the latest data is the rise in the number of teachers returning to the profession even as more are leaving and teachers’ reported wellbeing declines. The overall number of entrants has fallen by 3,900 teachers, driven largely by 4,200 fewer new graduates entering the profession. That is no surprise after the continued low recruitment to teacher training. However, the number of teachers returning to the profession after a break has increased by 600 since last year, and the number of returners to secondary teaching is up by 2,000 over the past two academic years. In secondary schools, that means the number of returners is now approaching the number of new entrants, which is a change from the past decade.

An increasing number of returners to education is a boon as the number of new entrants falls, but it also bolsters the experience of the workforce. Returners are typically experienced teachers and are likely to be more effective than new entrants, who are still learning the ropes. It’s unclear why more are returning to the profession but it is an extremely welcome fillip.

7…and pay growth doubled

Last year’s pay settlement was the most generous since 2010, with most pay points increasing by 6.5 per cent. That was reflected in the actual pay of teachers, which grew by nearly 6 per cent by November 2023, and even more than that once the late pay settlement was reflected in all teachers’ pay.

However, that pay growth was only announced by the government in July 2023 and most hiring of teachers is already completed by then, so it is unlikely to explain the change in returners. Since 2010, teachers’ real pay has fallen by 12 per cent and pay has also declined relative to other occupations. NFER’s work found that a teacher on the starting salary in 2010/11 would have been earning more than 38 per cent of full-time workers. In 2022/23, that same new starter would be earning more than only 29 per cent of workers.

Tackling the decline in pay is crucial for the incoming government if they are to solve the recruitment and retention crisis in schools. The Secretary of State for Education has decided not to respond to the STRB’s report before the election, which means the pay settlement will again come too late for headteachers to make concrete promises to their staff on pay. That lackadaisical approach to teachers’ pay is likely to continue to drive teachers out of the profession and make it harder to recruit new ones.

8. Silver linings in the gloom

The overall picture painted by the latest data is mixed. On one hand, the retention problems persist, leaders are leaving the profession at a growing rate, and recruitment remains a challenge. On the other hand, an improved pay settlement, the sustained retention of early career teachers, and the increase in returners to the profession offer reasons for hope. They suggest that efforts to improve the support for new teachers and to make the profession more attractive are having an effect and that there is a path to solving the recruitment and retention crisis in schools. That path, as EPI and others have been saying for several years, is to first pay teachers at a competitive rate and then to provide them with the support they need to stay in the profession. The government has made some progress in recent years but has not done nearly enough on either to turn things around. The next administration must do more to ensure that teachers are paid fairly and that they are supported to stay in the profession.