Today the Department for Education (DfE) released the annual statistics on widening access and participation in higher education, covering up to the 2022/23 academic year. The publication includes a wide range of data on progression rates to HE across England, broken down by a series of characteristics as well as the type of higher education to which students progress.

Through this data, we can investigate the ‘participation gap’ at higher education between two groups. For example, students who were in receipt of free school meals in school and those who were not. The DfE publication includes a series of charts on these gaps. However, to better understand the magnitude of inequalities in HE participation, we have transformed this data into ‘risk ratios’, or relative risks. Put simply, this analysis tells us how much more likely one set of students is to progress to university than another.

What is relative risk?

Relative risk is a measure used to compare the probability of an event (such as progressing to university) happening in one group compared to another. Whereas the progression rate gap tells us the absolute difference between two groups, the relative risk tells us the scale of the disparity. A relative risk of 1 would mean that the two groups are equally as likely to progress to university. Above 1 would mean that the numerator group is more likely to progress, and below 1 would mean they are less likely to progress.

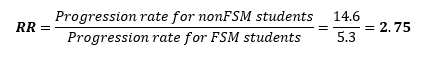

For example, in 2021/22, non-FSM students had a progression rate to high tariff higher education of 14.6 per cent, while FSM students had a progression rate of 5.3 per cent. We can calculate the relative risk for these groups as follows:

In this example then, the risk ratio for FSM vs non-FSM students would be 2.75, meaning FSM students are 2.75 times more likely to progress to high tariff universities than non-FSM students. This improves our understanding of the gap beyond just considering the difference in probabilities, which at just 9.3 percentage points might seem small.

With the explanation out the way, let’s take a look at the differing relative rates of progression between characteristics in the latest data.

FSM eligibility

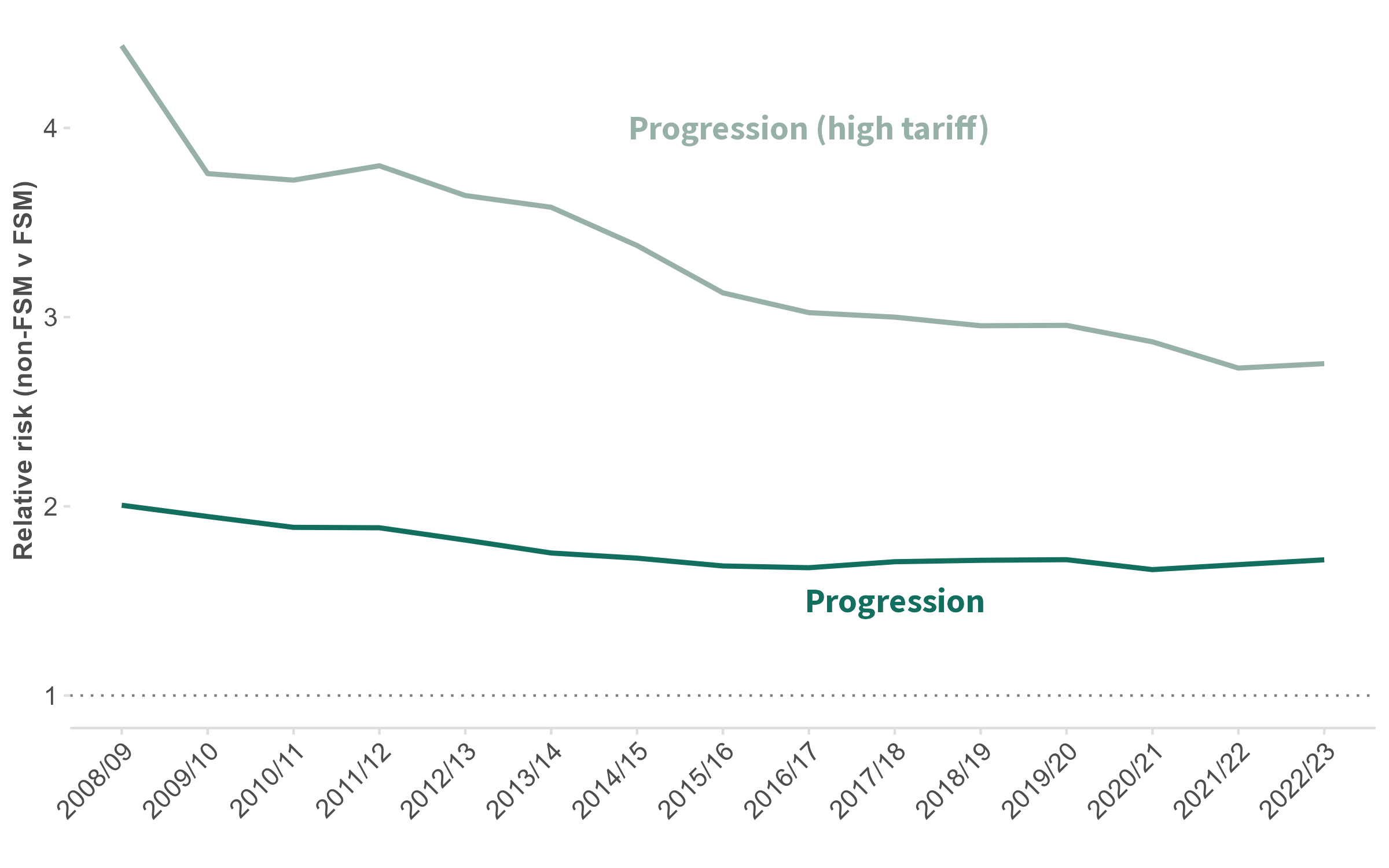

Comparing the relative progress rates for FSM students compared to non-FSM students we can see, perhaps unsurprisingly, that non-FSM students are far more likely to progress to higher education, with the non-FSM students twice as likely to progress during the last 15 years. Despite increasing participation in HE for disadvantaged students, the relative progression rate has only slightly narrowed throughout this period due to corresponding increases in participation for non-disadvantaged students with the relative progression rate now sitting at 1.72. For progression to high tariff HE however, greater progress has been made in closing the gap. In 2008/09, non-FSM pupils were almost 5 times as likely to progress to high tariff HE than their FSM peers, while in 2022/23 that has reduced to 2.75 times as likely.

Relative progression rate and high tariff progression rate (non-FSM vs FSM), 2008/09 – 2022/23

POLAR quintiles

POLAR is an area-based measure of higher education progression, classifying areas into quintiles based on the historic proportion of young people progressing to HE.

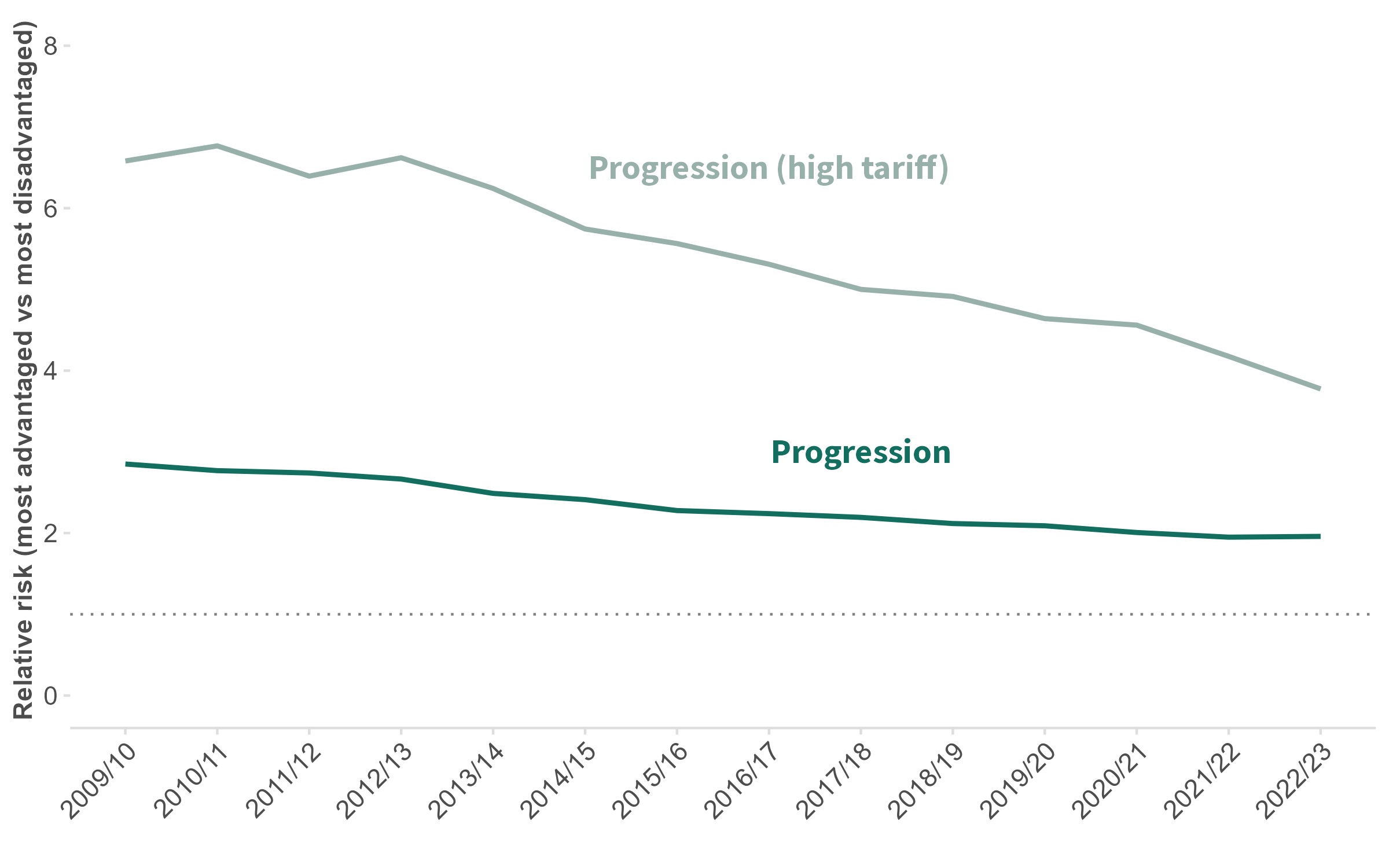

Given progression rates are baked into the measurement of POLAR quintiles, we would expect to see a large difference in relative progress rates when comparing the highest and lowest quintiles of participation. However, when comparing the rates, we can see some evidence of the success of the focus on improving access to students from areas of low participation. Across HE, students from the areas of highest participation are 1.96 more likely to progress to HE than students from the areas of lowest participation in 2022/23, compared to 2.85 times more likely in 2009/10. For high tariff HE this has fallen dramatically, down to 3.77 times more likely in 2022/23 compared to a staggering 7.0 in 2009/10.

Relative progression rate and high tariff progression rate (most advantaged POLAR v most disadvantaged POLAR), 2009/10 – 2022/23

School type

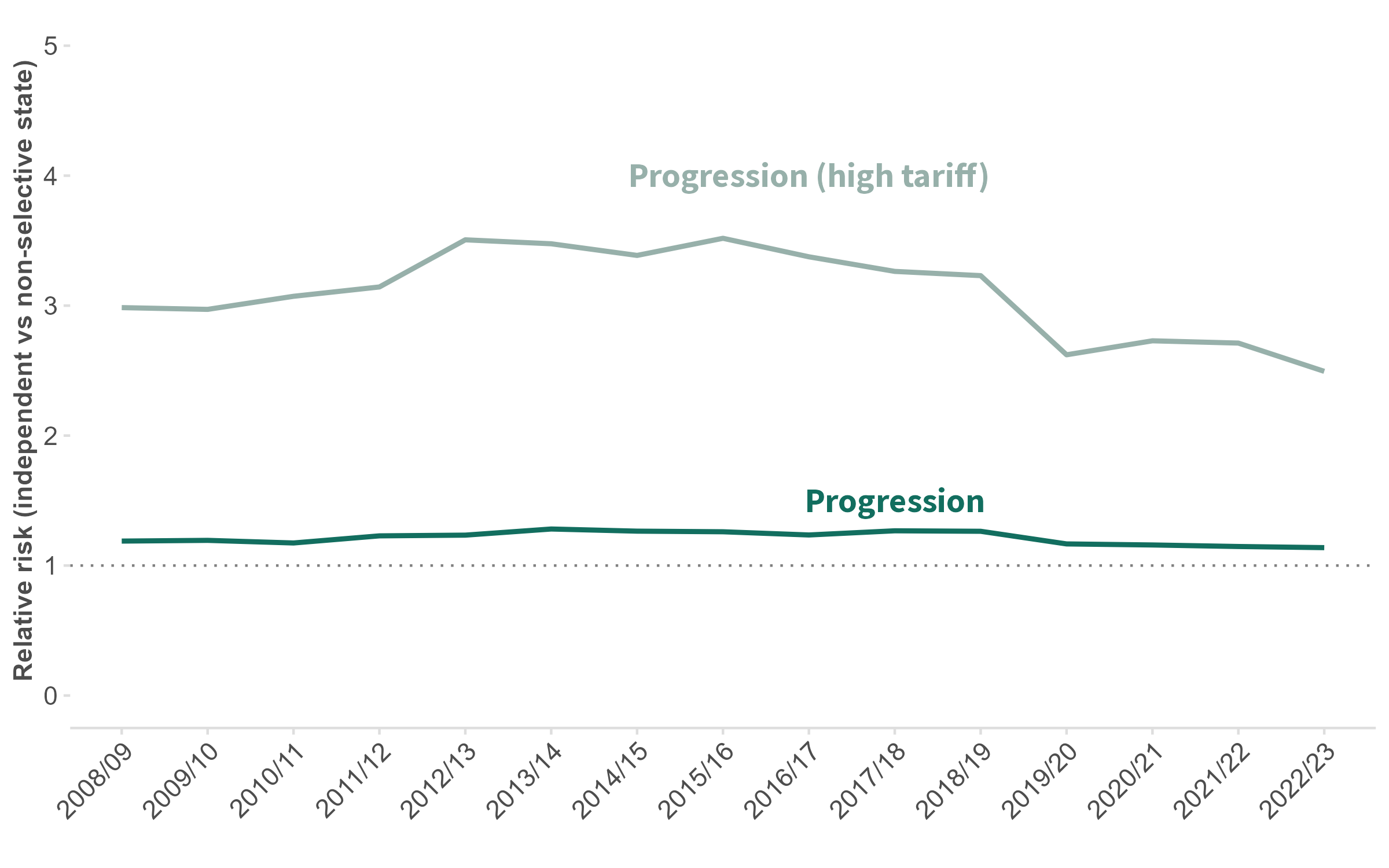

Another longstanding inequality of participation in HE is school type. Students from independent schools have historically been overrepresented in higher education, although many universities have aimed to broaden their admissions profiles in previous decades.

Across the whole HE system, participation is now almost equally likely across these groups. In 2022/23, independent school students were just 1.14 times as likely to progress to higher education than their non-selective state-educated peers. For high tariff HE however, there is a greater contrast: independent school students are 2.49 times as likely to progress to these providers in 2022/23, although this is down from a peak of 3.48 times more likely in 2013/14.

Relative progression rate and high tariff progression rate (independent schools v non-selective state schools), 2008/09 – 2022/23

Gender

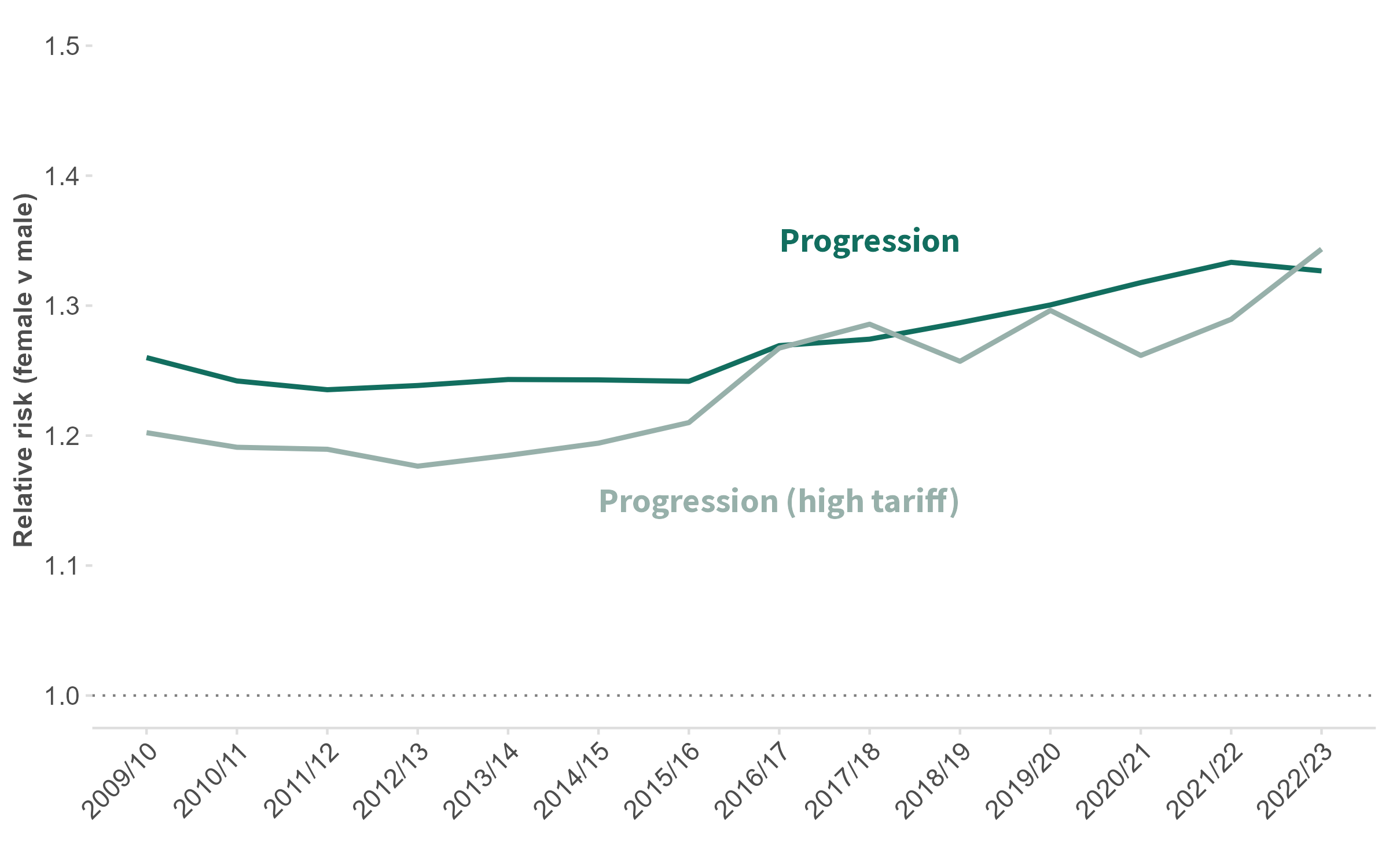

Finally, a quick look at gender. Our research on gender gaps in earlier phases of education has shown some narrowing in 2022/23 in the attainment gap that leaves male students behind their female counterparts. This is yet to filter through to higher education, with female students both more likely to attend all HE and high tariff HE at increasing rate (i.e. the relative risk is veering away from 1). Female students are 1.33 as likely to enter higher education as male students in 2022/23 compared with 1.26 times as likely in 2008/09. The high tariff HE rate has also increased, with female students now 1.34 times more likely to progress compared to male students in 2022/23.

For the second time in the last decade, the relative progression rate between female and male students for high tariff universities has overtaken the overall relative progression rate. In simpler terms, the difference in likelihood of progression between male students and female students is once again greater for high tariff universities.

Relative progression rate and high tariff progression rate (female v male), 2008/09 – 2022/23

Conclusion

Despite some progress in widening participation for disadvantaged students in recent years, today’s data shows worrying signs that that this progress has stalled, and might even be going in reverse.

The government must continue efforts to narrow this participation gap with an ongoing aim to address the financial burden of higher education faced by disadvantaged students. The government must also ensure that there are accessible and high-quality post-18 pathways offered to the majority of students who do not progress to higher education.