This week, students throughout the country received their A level grades and began the process of figuring out the implications for further study or entering the labour market. This analysis explores the policy background, before examining what we can see in the 2019 statistics on entries and attainment.

Policy context

This year marks the penultimate stage in the rollout of the new A level qualifications, introduced incrementally from 2016. Students getting their grades today were the first to take the new A level courses in maths, political studies, and many other subjects. The new A levels included changes in both content and assessment methods, with the aim of better preparing students for further study.

A level content was updated in line with recommendations from the higher education sector. Changes included incorporating more quantitative skills in psychology and economics and learning how to work with large datasets in mathematics.

The format of assessment was also changed. Exams are now at the end of A level courses, rather than throughout the year. Coursework was minimised and was only included when it was an essential part of assessing certain skills, such as in science practicals. Except for art and design subjects, coursework forms a maximum of 20 per cent of the A level grade.

AS levels, which students used to take in the first half of their A levels, are now a standalone qualification, worth 40 per cent of an A level in UCAS tariffs. They do not count in the A level offers universities make to students. As a result, there has been a steep decline in AS-levels since 2015, detailed below.

18-year-olds getting their results today were also the first to sit the new, more challenging, GCSEs in English and maths. These reforms led to concerns in some quarters that students might be “put off” from taking these subjects at A level.

Entry rates

A level entries have increased as a proportion of 18-year-olds While there has been a 1.2 per cent decline in the number of A level entries compared to last year (1.0 per cent lower for males and 1.3 per cent lower for females) this is against a fall of 2.1 per cent in the overall 18-year-old population.

Entries from sixth form and further education (FE) colleges have fallen more sharply, by 6 per cent. Given that disadvantaged pupils are more likely to study at these colleges, these students may now be following a narrower curriculum. These institutions have also been feeling the effects of funding pressures, with real terms per student funding falling by 16 per cent over the last decade, with FE colleges the hardest hit

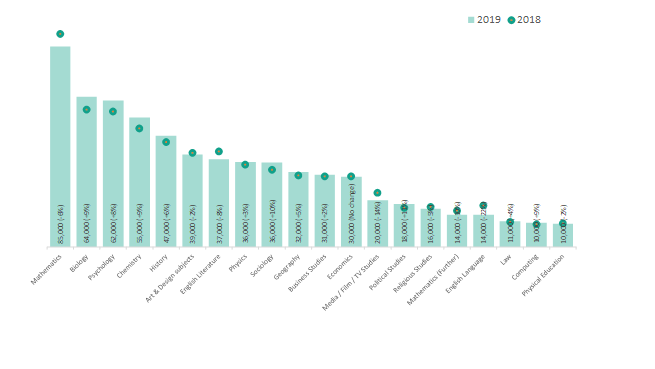

In terms of individual subjects, social sciences are on the rise, with political studies, psychology, and sociology seeing some of the biggest increases. Also popular are the science subjects; entry to chemistry and biology have risen by around nine per cent each. Overall, natural sciences, social sciences, and maths make up just over half of entries. Some of the largest declines were in English language, performing arts, and media studies, which fell by 22 per cent, 18 per cent and 14 per cent, respectively.

As outlined above, these A level students are the first cohort to have taken the reformed GCSEs in English and maths, and entry data shows a drop in the popularity of these subjects. English literature continues its decline, with an 8.1 per cent decrease on last year’s figures and mathematics also sees a dip of 5.8 per cent, having previously been on the rise (Figure 1). The government will hope that the recently announced maths premium, which offers schools extra funding for pupils studying mathematics A level, will boost numbers up again. Overall, these trends suggest that harder GCSEs could be putting children off continuing with English and maths, and the pattern could continue for other subjects affected by the GCSE reforms.

Figure 1: Number of entries per subject in 2018 and 2019

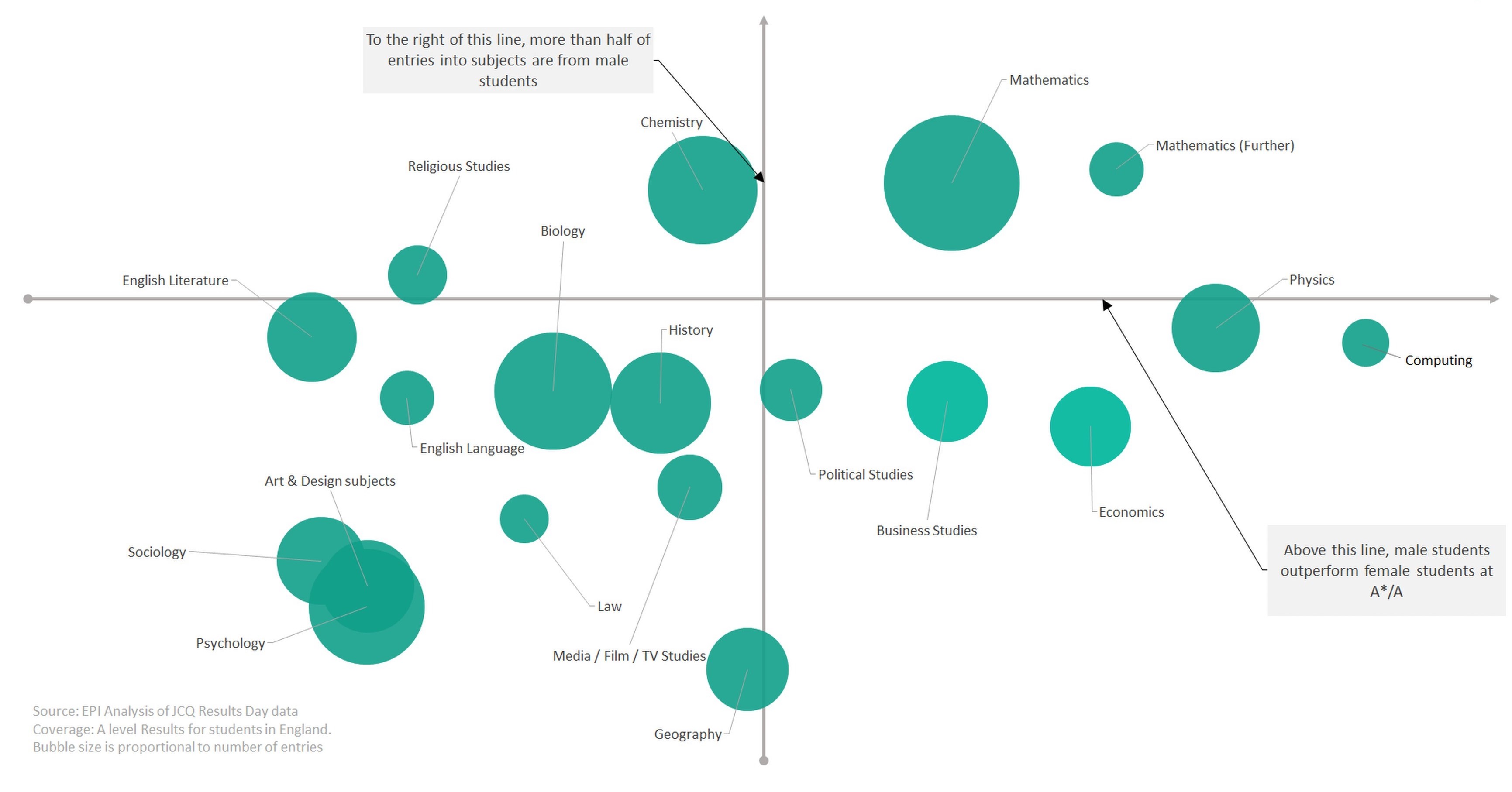

Female students are now taking sciences (biology, chemistry, and physics) at the same rate as their male peers. Despite an increase in physics entries, the biggest gains were made in chemistry and biology, and there remain big disparities between the subjects in terms of their gender mix – around three times as many males as females take physics, and nearly twice as many females and males take biology

It is a mixed picture for the recently ditched ‘facilitating’ subjects, with the sciences, history, geography, and Spanish performing well, while other languages and English literature decline.

Modern Languages continue their decline, with a reduction of five per cent compared to last year. The decline in languages mirrors the GCSE entries for this cohort, which saw 10 per cent falls in entry for French and German at GCSE, and a smaller fall in Spanish. Spanish has bucked the trend, with an increase of 4.5 per cent, overtaking French for the first time to become the most popular modern language.

As expected, AS level entries continue to fall by 56 per cent in England. There has been an overall decline of 91 per cent from 2015, the year before reforms of AS and A levels began. The decline in AS entries could lead to an even narrower curriculum, when the UK already has one of the narrowest curricula in the OECD.

Grades

The subjects with some of the largest proportions of pupils getting an A* or A were further maths, maths and French (with 53, 41 and 36 per cent of entrants achieving those grades respectively).

In terms of the subjects where students sat the newer GCSEs, grades have slipped in maths this year. Results were stable for English literature and English language.

For the rest of the new A levels, there has been a dip in performance in political studies, law, with stable results for media studies.

Figure 2 shows gender gaps in entries and the gender gaps in attainment. Overall, female students continue to score more A*/A than males in most subjects, particularly in geography, psychology and art and design subjects. In maths, further maths and chemistry subjects however, male students tend to score higher grades, and achieve slightly more A*/As overall.

Figure 2: Gender gaps in subject entries and attainment 2019

The best performing region in England was the South East, with 78 per cent of entries at A*-C, and 28 per cent of entries at A*/A. The East and West Midlands were the worst performing regions, with 73 per cent of entries at A*-C.

The North East was the only region to see an improvement in the proportion of students achieving an A grade from last year, with a percentage point change of 0.3. The East Midlands region saw the biggest fall in the proportion of students achieving an A grade, down by 2.1 percentage points compared to last year.

In results week, it is also important to look beyond the latest statistics and trends at A level, and consider the many thousands of students in England that decide to take alternative education pathways: this includes those that do not progress on to university, or those that do not take A levels after their GCSEs.

Students taking vocational qualifications such as BTECs are on the rise – with disadvantaged students disproportionately represented among these routes. Indeed, our research shows that over recent years, post-16 education routes have become increasingly segregated between the poorest and the rest.

Given these developments, when examining trends in educational attainment at this age, policymakers and commentators should consider taking a much broader view, and give equal consideration to the achievements of the half of young people in England who opt for different paths.