English as an Additional Language

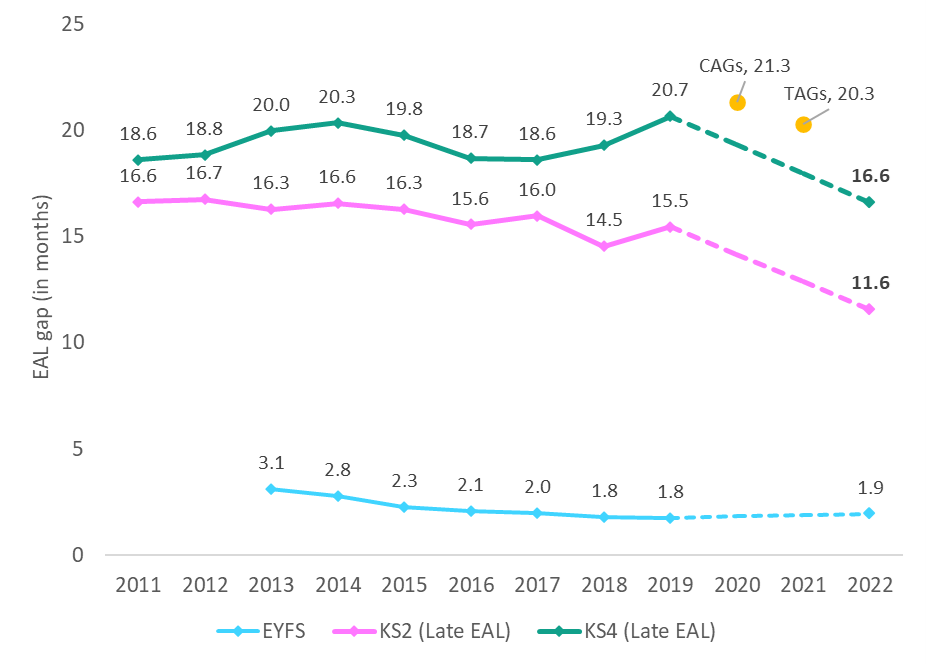

Around one-fifth of pupils in reception are recorded as having English as an additional language (EAL). In 2022, these pupils were 1.9 months behind their peers with English as a first language – a similar sized gap to the pre-pandemic period but a reduction since 2013 of over 1 month.

There is significant variation in attainment outcomes within the group of EAL learners, reflecting factors like English language proficiency and arrival time to the English school system. [1] Our previous research has shown there to be a severe attainment penalty for children who arrive late to the English state school system, which may be because there is little time to become proficient in English and learn the curriculum before the end of key stage assessments. We therefore focus on late-arriving pupils with EAL for our analysis of attainment gaps at later key stages.

Around 10,000 pupils arrived in the final two years of primary school with English as an additional language in 2022. These pupils had a gap of almost one year (11.6 months) compared to their peers with English as a first language. Although a sizeable gap, this is a significant reduction from the 2019 gap (of 15.5 months) and marks a faster rate of progress in narrowing the gap than over the pre-pandemic period 2011-2019.

The pattern is fairly similar at the end of secondary school, albeit with a bigger gap. In 2022, the late-EAL gap was 16.6 months – again a stark reduction on the 2019 gap by around 4 months. But whereas the key stage 2 gap had been narrowing before 2019, the key stage 4 gap had been on an upward path in the years leading up to the pandemic.

Figure E1: Pupils with EAL who arrive late to the English state school system are almost one year behind their peers at the end of primary school and almost 17 months behind at the end of secondary school

Exploring EAL gaps in more depth

The scale of gap-narrowing during the period 2019-2022 at both the end of primary school and secondary school among late-arriving pupils with English as an additional language is far more rapid than prior to the pandemic. We find evidence that compositional shifts within the EAL group may have contributed towards this gap narrowing. Specifically, within the late-EAL group there has been an increase in higher-attaining ethnic groups and a reduction in lower-attaining ones.

Among late-arriving pupils with EAL at the end of primary school, there has been a very marked increase in the numbers of Chinese pupils, by around ten-fold over the period 2019-2022. This far outweighed the growth of any other minority group, with the next biggest increase (of 47 per cent) among pupils of Any Other Asian background. Both these subgroups have better attainment, on average, than other late-arriving pupils with EAL – and in the case of the Chinese pupils, they are unique in having higher attainment than even pupils with English as a first language. By contrast, over the same period, the number of Gypsy Roma pupils almost halved, with large reductions (of around 40 per cent) also seen among pupils of Any Other White backgrounds and Any Other Black backgrounds. These three subgroups have lower attainment on average, than other late-arriving pupils with EAL.

Looking at patterns among late-arriving pupils with EAL at the end of secondary school, once again there is very marked growth among Chinese pupils whose numbers increased by around 250 per cent over the period 2019-2022. There were also smaller but still sizeable increases (of 60 per cent) among Indian and Pakistani pupils.[2] Relative to other late-arriving pupils with EAL, Chinese and Indian pupils have high average attainment levels – and as at key stage 2, Chinese pupils have higher attainment than pupils with English as a first language. Meanwhile, the number of Gypsy Roma pupils again declined (by 37 per cent), second only to the reduction among White and Black Caribbean pupils (of 38 per cent). These pupils trail their peers with English as a first language by over three years for Gypsy Roma pupils – comparable in size to attainment gaps for pupils with statutory EHCPs – and two years for White and Black Caribbean pupils.

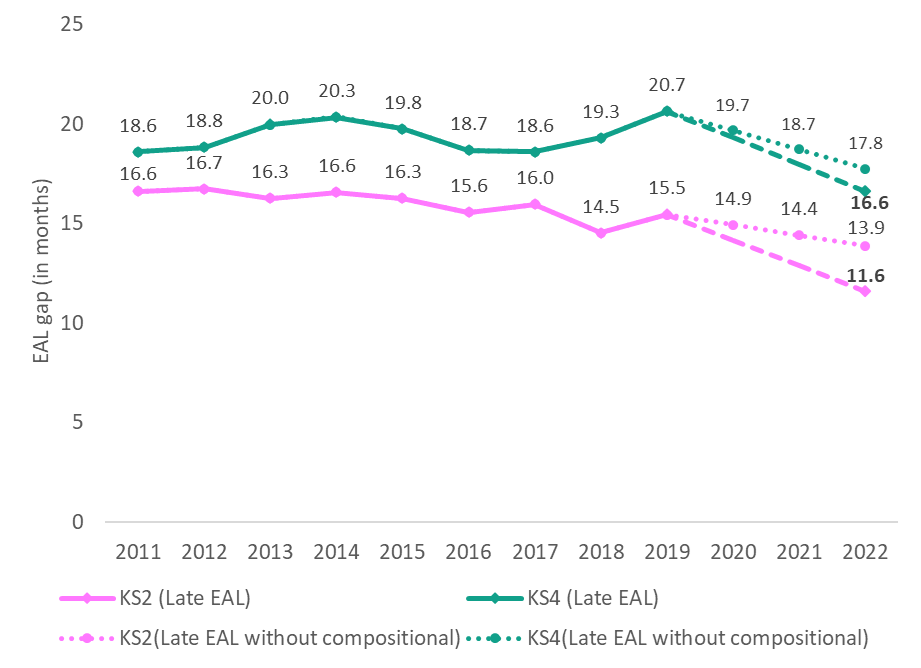

It is therefore clear at both key stages 2 and 4 that there have been sizeable compositional shifts within the late-EAL group during the post-pandemic period towards higher-attaining ethnic groups and away from lower-attaining ones. To get a sense of how important these shifts have been in the narrowing of the EAL gap between 2019-2022, in figure E2 we re-estimate the 2022 gap, assuming the ethnic composition remains as in 2019. This means that any remaining gap-narrowing that is visible reflects only within-group gap-narrowing (i.e. improved attainment for a given ethnic group), as opposed to any compositional shifts between 2019 and 2022.

We can see that in 2019, the gap for late-arriving EAL pupils at the end of primary school was 15.5 months. By 2022, figure E2 shows that this had narrowed by 3.9 months to 11.6 months. But if we strip out the compositional shifts over this period, the 2022 gap would have been 13.9 months – a smaller reduction of 1.6 months. This means that most (2.3 months – equivalent to 60 per cent) of the gap closure at key stage 2 is due to compositional effects rather than gap-narrowing within ethnic groups.

Figure E2: The narrowing in the gap for late-arriving pupils with EAL between 2019 and 2022 at both key stages 2 and 4 appears to be driven at least partly by compositional changes within the EAL group

The story is somewhat similar at the end of secondary school but less marked. The GCSE gap for late-arriving EAL pupils was 20.7 months in 2019 which narrowed by 4.0 months to 16.6 months by 2022. Stripping out the compositional shift over this period in figure E2 shows that the 2022 gap would have been 17.8 months, a reduction of 2.9 months. This means that compositional effects are still a driver of the EAL gap-reduction at GCSE (accounting for just over one-quarter of the overall reduction) but not as important as at key stage 2. Most of what is driving the gap reduction at GCSE is due to narrowing gaps for individual ethnic groups.

That compositional shifts have been a driver in the reduction in the overall late-arriving EAL gap between 2019-2022 – particularly at key stage 2 – is important because it means that underlying educational inequalities are not improving as fast as the headline EAL gap would suggest. It is also unclear whether this progress will be sustained in future years unless compositional changes continue to reinforce recent patterns – for example, continuing the unprecedented recent growth in high-attaining Chinese pupils, which may be linked to the Hong Kong British Nationals (Overseas) Welcome Programme.[3] It remains the case that overall, late-arriving EAL pupils face significant educational challenges as, on average, these children are almost a year behind their peers at the end of primary school and 16.6. months behind by the end of secondary school which are similar sized gaps to those we estimate for disadvantaged pupils.

[1] Children with EAL have widely varying levels of English proficiency: some have no English and some are fluent multilingual English-speakers; some may have lived in English-speaking countries or have been educated in English throughout their childhood.

[2] There was also a 70 per cent increase among pupils with ethnic “information not yet obtained”.

[3] This has supported the resettlement of families from Hong Kong since January 2021. Data published by the Department for Education indicates that there have been 8,800 offers of primary school places (across all year groups, not just in year 6) and 4,300 secondary school places (across all year groups, not just in year 11) for the 2021/22 academic year for children from Hong Kong.