Last week we published an estimate of the effects of potential changes to fees and student loans’ conditions for graduates, public spending and universities. It was based on The Times’ speculation on the Chancellor’s plans for higher education funding. Our findings can be found on our website and on The Times Higher Education.

Following this, on the opening day of the Conservative Party Conference, Theresa May shed some light on the Government’s proposed changes to higher education funding. Although there is still a lack of policy detail, there are two changes that are now quite certain. First, tuition fees will be frozen at £9,250, which means they will not be uprated in line with inflation (as previously proposed). Second, the repayment threshold will rise from £21,000 to £25,000.

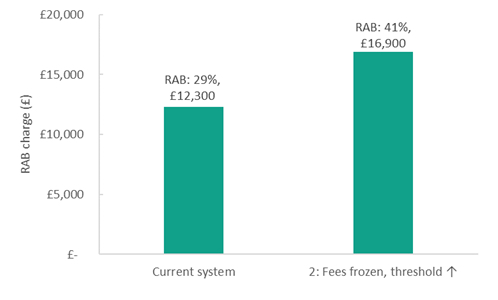

We have updated our analysis from last week to reflect these latest announcements.[1] The first scenario (baseline) is a replication of the current system: tuition fees are uprated with the inflation every year and the repayment threshold stays on £21,000 until 2020, where it will start to raise in line with annual inflation. The second scenario assumes that both the freeze on tuition fees and the new repayment threshold are introduced as early as next academic year, and that the repayment threshold increases with inflation every year. We assume that for both scenarios the interest rate remains unchanged.

Increase in public subsidy

Last week we published an estimate of the effects of potential changes to fees and student loans’ conditions for graduates, public spending and universities. It was based on The Times’ speculation on the Chancellor’s plans for higher education funding. Our findings can be found on our website and on The Times Higher Education.

Following this, on the opening day of the Conservative Party Conference, Theresa May shed some light on the Government’s proposed changes to higher education funding. Although there is still a lack of policy detail, there are two changes that are now quite certain. First, tuition fees will be frozen at £9,250, which means they will not be uprated in line with inflation (as previously proposed). Second, the repayment threshold will rise from £21,000 to £25,000.

We have updated our analysis from last week to reflect these latest announcements.[1] The first scenario (baseline) is a replication of the current system: tuition fees are uprated with the inflation every year and the repayment threshold stays on £21,000 until 2020, where it will start to raise in line with annual inflation.

Figure 1. Increase in the public subsidy if tuition fees were frozen and repayment threshold raised to £25,000

Same student debt, more progressive conditions

It is noteworthy that the debt students would leave university with if fees were frozen would not differ significantly from the level they accrue now: it would only go down from £45,800 to £44,400. In our piece last week, we stated that lowering interest rates would make the system less progressive as, under the current system, high earners are net contributors as they pay back more than they borrow. Although further changes to interest rates cannot be ruled out in the current policy environment, our alternative scenario does not contemplate any change on that front.