The curriculum and assessment review (CAR) as it applies to 16-19 education is as much about qualifications as it is about curriculum and assessment. For school age children, the national curriculum sets out the content that must be taught and/or examined. Post 16, students have greater choice in the subjects and type of qualifications they study towards, and specific content is not mandated.

As such, there is not a singular post 16 curriculum to be reviewed, instead the CAR cuts across multiple themes which are regularly the topic of post 16 policy debate, including:

-

- How the current qualification offer meets the needs and aspirations of learners.

- The role of English and maths qualifications, and other core skills needed to succeed.

- Transitions from key stage 4 into post 16 study.

- The suitability and accessibility of available study programmes for students from more vulnerable groups, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

This analysis piece presents some initial findings from our Nuffield funded project ‘Beyond teacher assessed grades: Post-16 education choices and COVID-19’ which are relevant to the CAR.

We will publish full findings including modelled results, in collaboration with the Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunity at UCL, early in 2026.

In this piece, we aim to provide a more nuanced overview of the study programmes students from different backgrounds are pursuing, their ability to complete these study programmes, and how trends have changed in recent years. Our key findings are as follows:

Key findings:

- Technical and applied level 3 courses have been increasing in popularity in recent years, as have mixed study programmes which combine these courses with A levels. This suggests that students value flexibility in their post 16 courses, and it will be important to retain this as the roll out of T levels continues.

- More students chose level 3 study programmes following the higher GCSE grades awarded under centre and teacher assessed grades (CAGs & TAGs) during the pandemic. This suggests that more students aspire to study at level 3 than are currently able to do so, as they are limited by their GCSE results.

- Level 3 retention rates dropped for the cohorts awarded CAG/TAG GCSEs, implying that some of the students that entered higher level qualifications struggled to complete them. However, retention rates would have dropped further if all of these additional students were not ready for level 3 courses. We have not been able to take the wider effect of the pandemic on retention rates into account, and there will always be a difficult balance between course access and retention. Nevertheless, these findings do not provide strong evidence that course entry requirements are too demanding, but there is a case for post-16 providers to take nuanced decisions about access to level 3 qualifications – some students who narrowly miss entry criteria may still be ready for level 3 study. Efforts to help more students study at level 3 should focus on improving outcomes by the end of key stage 4, or by encouraging more three-year study programmes post 16, which allow students to progress to level 3 qualifications.

- English and maths GCSEs play a pivotal role in access to level 3 qualifications, in particular A levels. However, the majority of students that started working towards English and maths resits alongside level 3 qualifications, were still able to complete their main study programmes. Most level 3 courses rely on reasonable literacy and numeracy levels. However, GCSE English and maths results below grade 4 should only restrict access to level 3 courses where key elements of students’ main study programme are dependent on proficiency to this level.

- There has been a post-pandemic increase in the proportion of students that are not working towards any qualifications or an apprenticeship at age 16. This is particularly prevalent amongst lower attainers. There are several plausible hypotheses for why this may be:

-

- Increasing absence rates at school age may signal a broader disengagement from the education system which is persisting into the 16-19 phase.

- The lowest attaining students are not well catered for in the current post 16 system, or:

- There are difficulties around access to and information on which courses would be most suitable.

All of these scenarios must be considered when reviewing the qualification offer, Careers Information Advice and Guidance (CIAG) policy, and the roles schools must play in supporting their most vulnerable students in their transition to sixth form or college.

- Students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds were less likely to begin level 3 qualifications at age 16, even when compared to students with similar prior attainment. This suggests that disadvantaged students are systematically more likely to be studying at a level lower than they may be capable of, and the CAR should pay great attention to this. We will conduct further research to identify where in the system this is happening, and the qualifications or subjects for which it is most prolific.

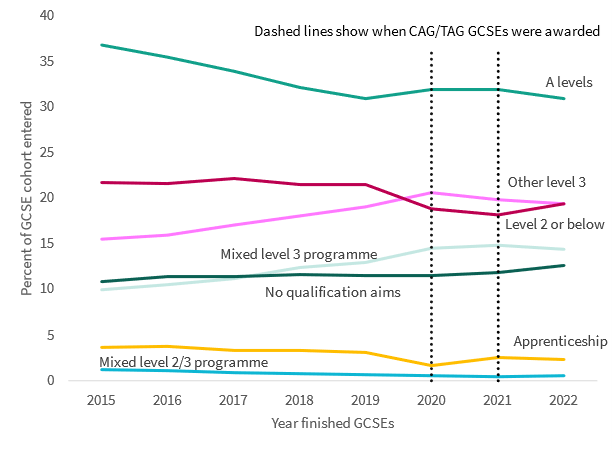

Figure 1: Enrolments to post 16 study programmes, by year completed GCSEs[1], [2]

Figure 1 shows enrolments to different study programmes since 2015 and confirms that A levels continue to be the most popular choice. Of those that finished their GCSEs in 2022, 31 per cent began an A level-only study programme at the start of the 2022/23 academic year.

19 per cent of students opted for other (non-A level) level 3 qualifications, which are typically applied or technical offerings, with a further 14 per cent pursuing a mixed programme combining these with A levels.

A substantial proportion (20 per cent) of students entered qualifications at level 2 or below (excluding English and maths resits), a small minority of which (3 per cent) combined these with level 3 qualifications.

A small proportion of students were on apprenticeship programmes, and the rest did not begin study towards any substantial qualifications at the beginning of the 2022/23 academic year.

Notably, the proportion of students opting for A level-only programmes had been declining prior to the pandemic. This was mirrored by an increase in the popularity of technical/applied level 3 qualifications, and an increasing demand for mixed study programmes which combine these with A levels. These trends reinforce the desire for flexibility in study programmes and suggest that if a more binary choice between A levels and T levels becomes the norm, it will not meet the aspirations of a substantial and growing number of young people.

Trends in take up for other pathways were largely stable prior to the pandemic, but the study choices of 2020 and 2021 GCSE finishers were quite different. This reflects the shock of the pandemic and the different grading approaches that the Department for Education (DfE) and Ofqual implemented in these years. Higher GCSE grades were awarded in 2020 and 2021, and the data suggest that students opted for higher level, more challenging post 16 courses as a result.

We can see this effect clearly by observing the decrease in enrolments for qualifications at level 2 or below, alongside increased demand for level 3 qualifications, spanning A level, vocational and mixed options.

Students typically apply for A levels before they sit their GCSEs. This means the observed changes will have arisen from a combination of:

- More students meeting their conditional offer requirements than usual, allowing them to pursue their first choice of study.

- More students changing their applications to higher level courses upon receiving their GCSE results.

- Students anticipating higher grades than usual in 2021, the second year of cancelled exams, and choosing higher level courses as a result.

Each of the above scenarios suggests that the courses available to students are not always meeting their aspirations. That is to say that given the opportunity, many students opted for higher level, more challenging courses.

We explore entry requirements and course completion further in the following sections looking at English and maths resits and retention rates.

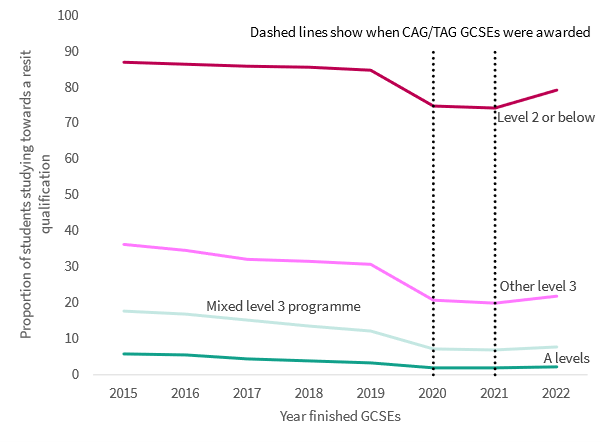

Figure 2: Proportion of students enrolled on each post-16 pathway that were studying towards an English/maths resit qualification.

Figure 2 shows the proportion of students enrolled to each pathway that were also studying towards an English or maths resit qualification. Students are required to continue study towards English and maths qualifications if they had not achieved grade 4 or above by the end of key stage 4.

We can see from figure 2 that the vast majority of students that were enrolled on level 2 (or below) study programmes were required to work towards an English or maths resit qualification. The resit rates for those doing level 3 qualifications, in particular A levels, were much lower. This reinforces the role of GCSE grades in the post 16 study choices students make. Of all resit students, almost 60 per cent were studying at level 2 or below, while less than a quarter were studying towards a level 3 qualification.

There was a decrease in the proportion of students working towards a resit qualification in 2020/21 and 2021/22, regardless of their main study programme. This was to be expected as the overall number of students required to resit decreased during the pandemic, as higher GCSE grades pushed more students over the grade 4 threshold.

Although we still see this decrease for A level students, the prevalence of having to resit English and maths qualifications was already very low, and the post pandemic dip was far less pronounced.

Having achieved grade 4 in English and maths is often an entry criterion for A level study, so it is unsurprising that the proportion of A level students having to resit has remained consistently low. This suggests that many of the ‘new’ A level students in the wake of the pandemic shown in figure 1, were able to study A levels because higher GCSE grades meant they met the English and maths requirements.

More students studying other (non-A level) level 3 qualifications would have met the English and maths grade 4 criterion during the pandemic too. However, for these qualifications it does not appear to be as much of a pre-requisite, as a substantial proportion of students studying towards other level 3s, were also working towards a resit in any given year.

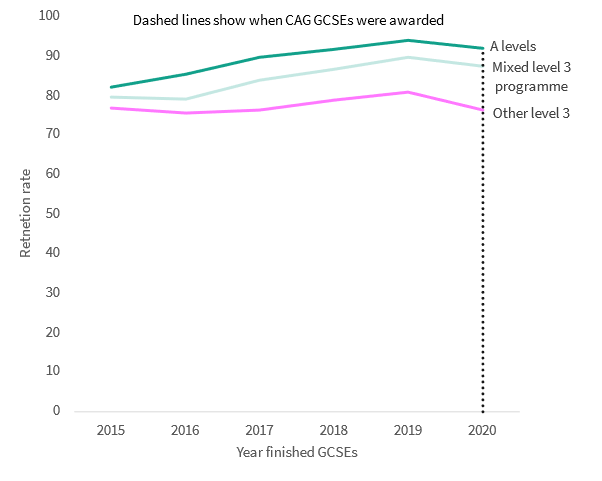

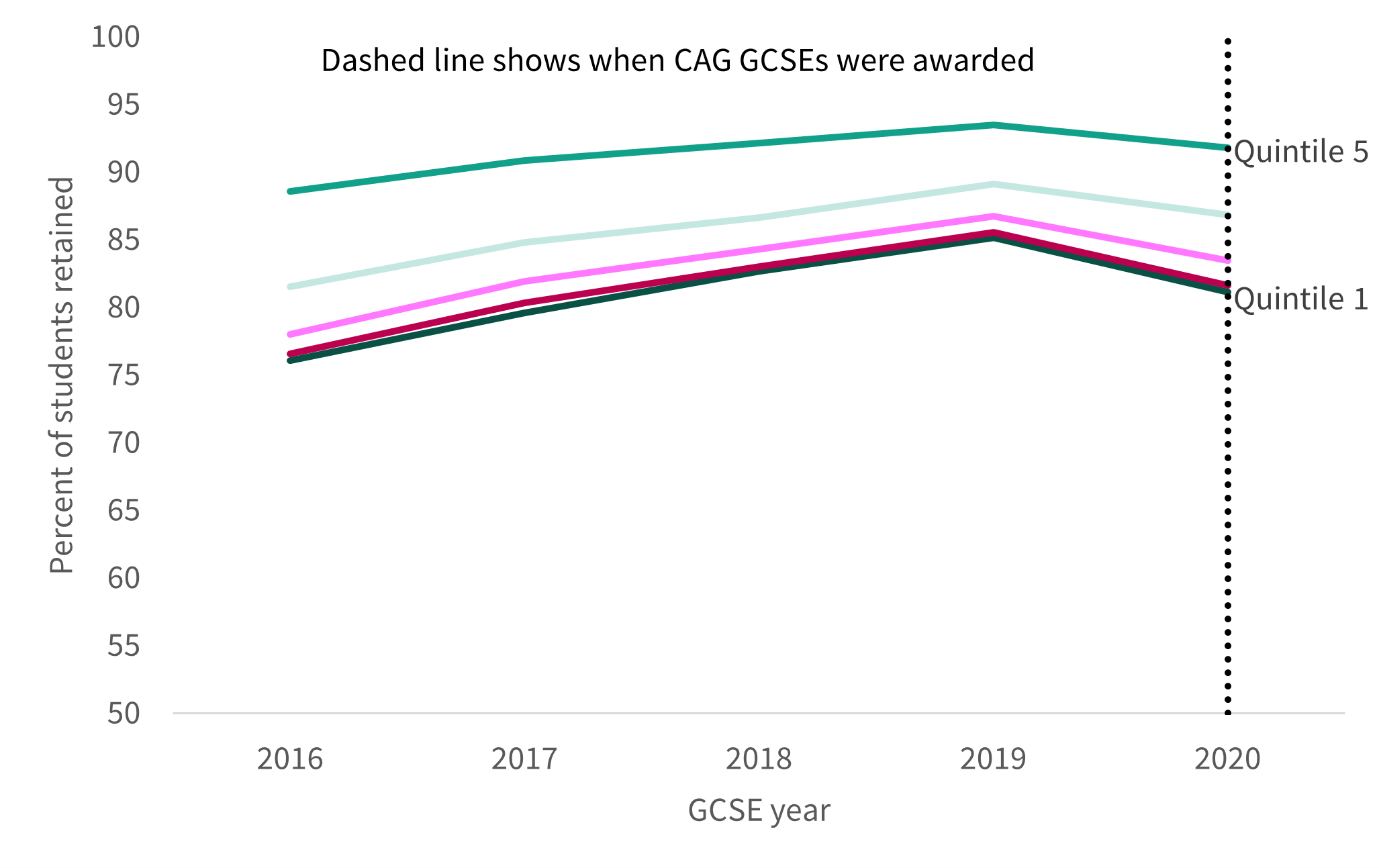

Figure 3: Retention rate by level 3 study programme[3],[4]

Figure 3 shows that there was a decrease in retention rates across level 3 qualification-based pathways for those that took their GCSEs in 2020. This suggests that those who opted for higher level study because they received better GCSE grades than they would have done in a usual year, were more likely to struggle to complete their courses. However, this effect may be overstated as we are not able to disentangle the drop in retention rates as a result of changing entry patterns, from broader post pandemic effects such as increased absence, and worsening mental health.

These findings suggest that on the whole entry requirements are not disproportionate and do a good job of indicating whether students are likely to be able to finish their courses. However, there are likely to be marginal cases where entry requirements are unduly restricting students that would have achieved positive level 3 outcomes given the opportunity, reinforcing the need for some discretion to be applied in admissions.

Overall, to enable more students to study at level 3, the focus should be on improving attainment by the end of key stage 4. Improving access to three year post 16 study programmes in which the first year acts as a stepping stone to level 3 study, may also be helpful.

We can further break down retention rates according to whether or not students were required to work toward an English or maths resit.

For those finishing their GCSEs in 2019 (the most recent pre-pandemic year), 85.4 per cent of A level students that were studying towards a resit qualification completed their A level study, compared to 94.2 per cent who were not required to work towards a resit.

Although this difference shows a greater completion rate amongst those with the better English and maths skills, the vast majority of A level entrants that were working towards a resit qualification were still able to complete their courses. For other level 3 students, the retention rate gap between resit and non-resit students was just 4 percentage points. This shows that for many students, grade 3 or below English and maths at the end of key stage 4 was not prohibitive to completing their level 3 study programme. Our forthcoming analysis will explore how this differs for those who did/did not pass their resit qualification, and how these findings vary by subject area.

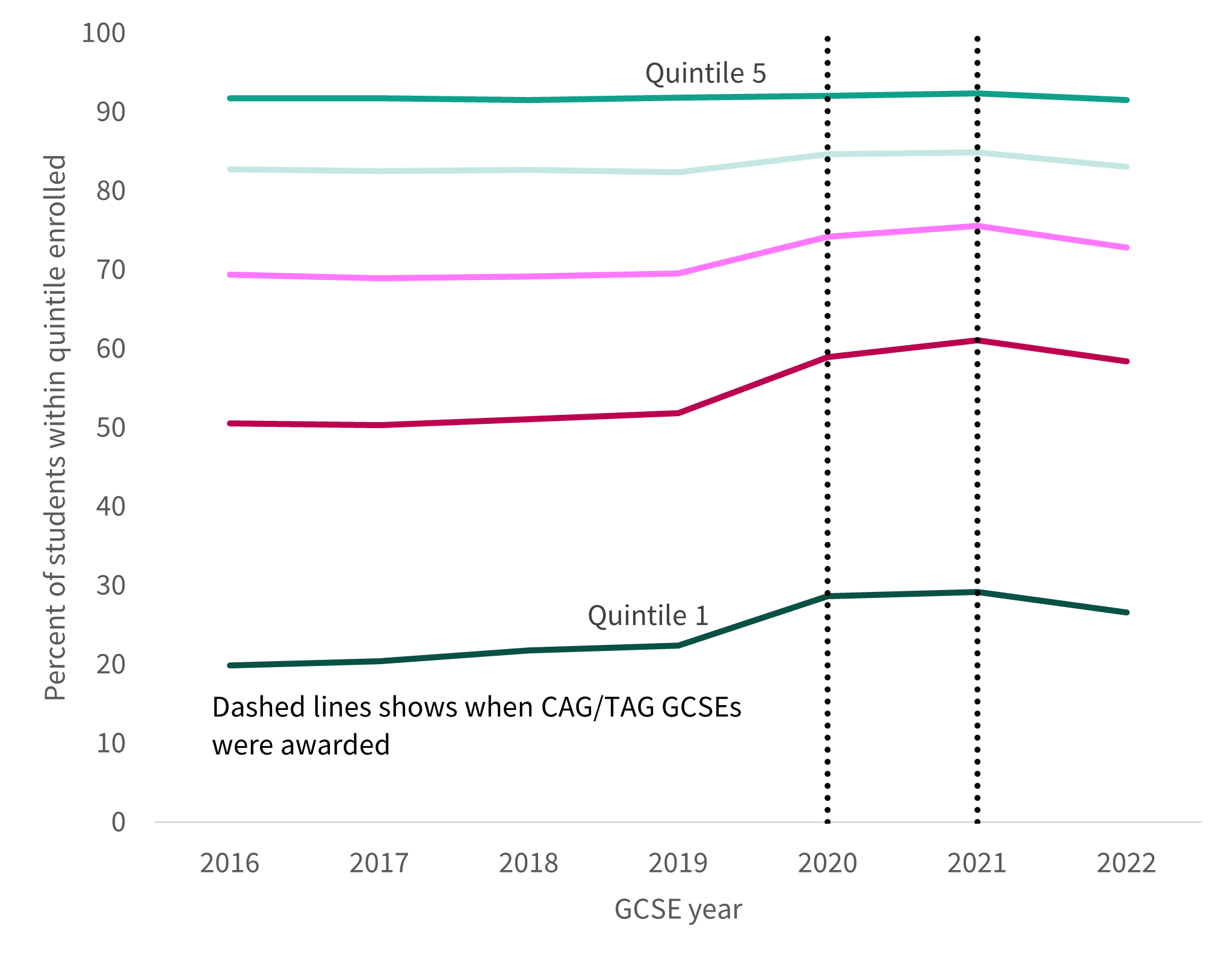

Figure 4: Enrolment to level 3 courses, by key stage 2 prior attainment quintile

We use key stage 2 rather than key stage 4 prior attainment as these results were unaffected by the pandemic and remain a strong predictor of 16-19 outcomes. However, the findings are still similar if we use key stage 4 English and maths GCSE results to create the quintiles.

Figure 4 demonstrates that the increase in enrolments to level 3 qualifications in 2020 happened across the attainment distribution, with the most pronounced effects in the lowest three prior attainment quintiles. There is a ceiling effect, as those with the highest prior attainment were mainly already entering level 3 qualifications.

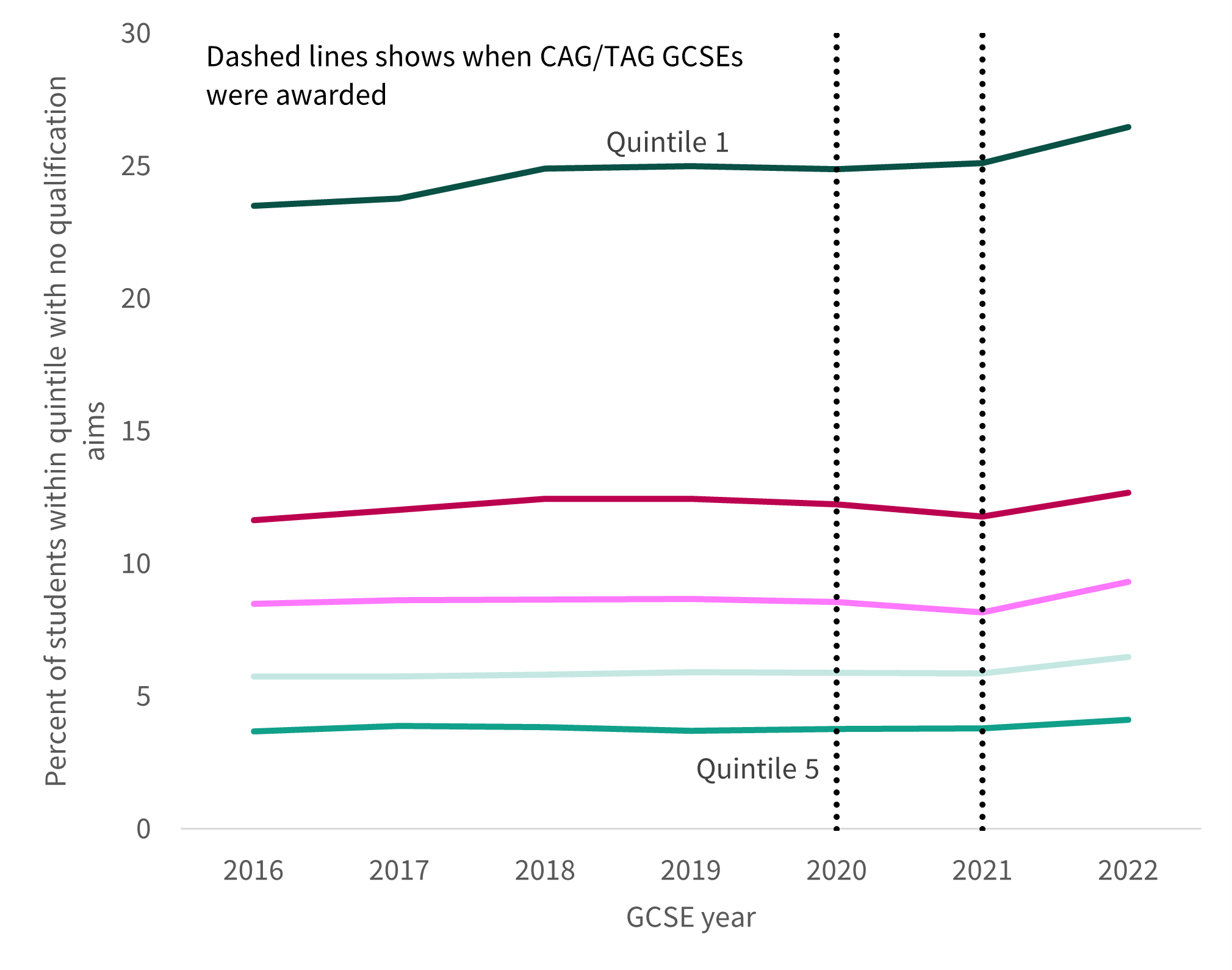

Figure 5: Students enrolled to no qualification aims or apprenticeship activity at the beginning of year 12, by key stage 2 prior attainment quintile

Figure 5 shows that lower attaining students were far more likely to have no active, substantial qualification aims at the beginning of their first year of post 16 study. We also see that there was a very large gap in the rate for students in the lowest prior attainment quintile compared to all others. These young people may have other, non-qualification activity that our analysis is not picking up or start other aims such as apprenticeships later in the year. However, the systematic lack of qualification enrolment for lower attainers at the beginning of year 12 suggests that the end of secondary school is a particularly risky transition point for these students.

It is also notable that this trend appears to have worsened since the pandemic, when exam-based GCSE grading had returned. This may be related to the increased absence rates observed at key stage 4, which have persisted since the pandemic.

Figure 6: Retention rate of students that began level 3 courses by key stage 2 prior attainment quintile

Figure 6 shows that there has been a gradual increase in retention across all key stage 2 prior attainment quintiles, up until the cohort affected by centre assessed GCSEs, for whom the trend reversed. The decline for the cohort starting their post 16 study in 2020 was greatest amongst the lowest prior attainment quintiles. Interestingly, although we saw no notable change in entries to level 3 qualifications amongst students in the highest prior attainment quintile, their retention rates still dropped slightly. This suggests that there are factors beyond changing entry patterns affecting retention rates for the 2020 GCSE cohort. This is unsurprising given the impact of school and college closures and the wider impact of Covid during this period, including increased absence and worsening mental health.

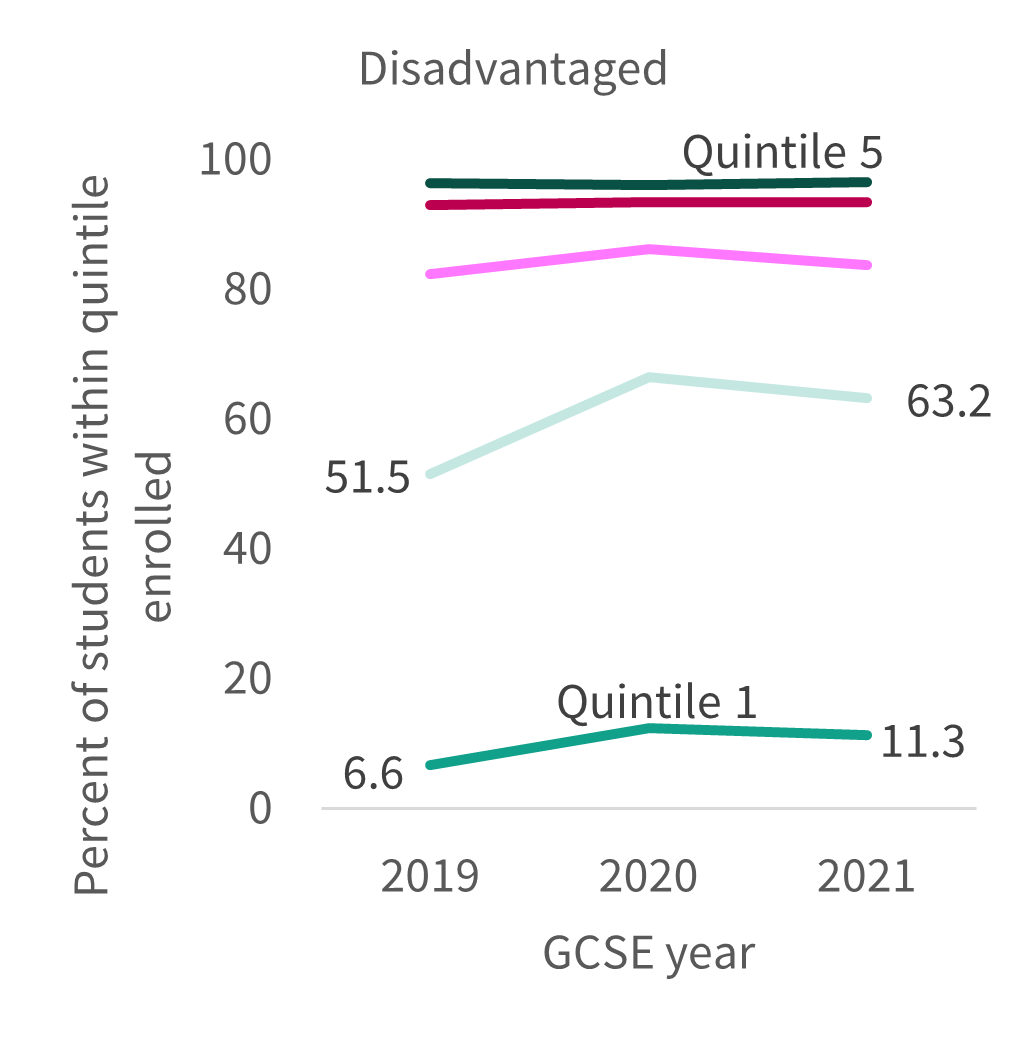

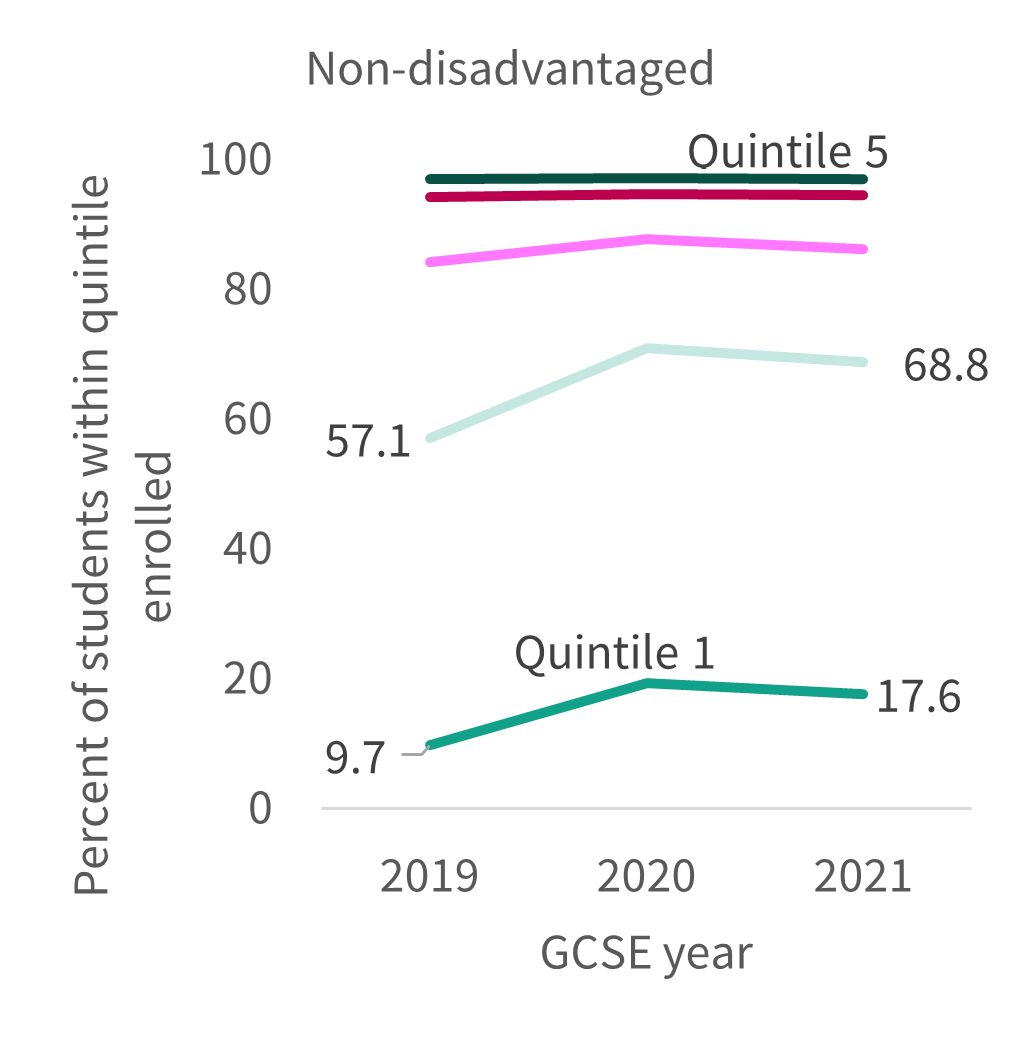

Finally, we look at enrolments to level 3 pathways by disadvantage status.

Figure 7: Enrolment to at least one level 3 qualification by disadvantage status and key stage 4 prior attainment quintile[5]

Figure 7 shows that disadvantaged students[6] in the bottom two prior attainment quintiles were less likely to begin level 3 qualifications than non-disadvantaged students, but that these differences were not present in the higher quintiles.

The lower quintiles are of most interest as over 60 per cent of disadvantaged students are accounted for within quintiles 1 and 2, while only 6 per cent are in quintile 5.

The charts show that the majority of disadvantaged students are less likely to study at level 3 than non-disadvantaged students, even compared to students with similar English and maths GCSE results to themselves.

This requires a more in-depth analysis but tentatively suggests that there are disadvantaged students in particular, who are systematically studying at a lower level than they might have been capable of. Careers Information and Guidance (CIAG) policy should be mindful of this, and strategies developed to help all young people reach their potential.

Our full report due early in 2026 in collaboration with the Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities at UCL, will include a new ‘mismatch’ methodology considering qualification and subject level choices in the 16-19 phase, to better understand where these differences by student characteristics are materialising. We will also include versions of our analysis presented here, which adjust for differences in student, provider and area level characteristics, and further analysis of mismatch in higher education entry during the pandemic.

This research is kindly funded by The Nuffield Foundation.

The Nuffield Foundation is an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance social well-being. It funds research that informs social policy, primarily in Education, Welfare, and Justice. The Nuffield Foundation is the founder and co-founder of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. The Foundation has funded this project, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. You can read more about their work here.