Introduction

For the first time since the controversy over algorithm-generated grades in 2020, an education story has dominated the headlines and broadcast media for almost a week. But this isn’t the spotlight on education that anyone wanted, not least the Department for Education.

The media interest was triggered when, late last week, the DfE issued emergency guidance to schools that were identified as having, or could potentially have, Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (RAAC). RAAC is a type of building material that was commonly used from the 1950s to the mid-1990s and which has since been identified to have serious safety concerns. Last week’s guidance from the DfE required all schools to close any spaces (this could include cupboards, classrooms or entire buildings) in which RAAC has been found.1

Since that guidance was published, dozens of questions have been asked about what went wrong and what led to the latest intervention from the DfE, just one day before many schools in England opened their doors (or not) for the new academic year. There are a number of complex, interacting issues that have led to this and in this blog, we seek to shed some light on those issues and what we should be looking out for next.

Timing is key…..

The public, understandably, want to know who knew what and when, and why the DfE has left it so late in the summer holidays to issue this latest guidance.

Safety concerns associated with RAAC were first flagged in the mid-1990s, following a report by the Building Research Establishment, although it’s unclear whether successive governments did anything about the issue in schools following that warning.

It wasn’t until July 2018 that the DfE published guidance for schools, highlighting the safety concerns associated with RAAC. This was in response to what the DfE has described as a “building component failure” but which has been reported by the BBC as the falling of a concrete block from the ceiling of a school in Kent.

Since the summer of 2021, the has DfE assessed the threat to safety in school buildings as a “critical risk”, yet the spending settlement from the Treasury fell short of what was needed (more on that, below) and further action was not taken until spring of the following year.

In March 2022, the DfE sent a questionnaire to schools, asking if they had RAAC on their school estate. Pausing there for a moment, this does beg the question of why the DfE waited almost four years before taking further action to identify schools with RAAC. It’s reasonable to assume that the Covid-19 pandemic played a part in this delay. From March 2020, the DfE had to respond rapidly and divert considerable resources (financial and human) to ensuring that pupils were able to continue learning safely during the peak of the pandemic.

Of the 156 schools that were initially identified as having RAAC (from the March 2022 questionnaire), 52 were supported to put mitigations in place, seemingly based on the DfE’s risk assessment at the time. However, following further incidents of other building failures caused by RAAC over the summer, the DfE issued guidance on 31st August to require all schools with known instances of RAAC to vacate the affected area. Not only did this pose considerable logistical challenges for the schools affected, but school leaders have also been frustrated that it happened on the eve of the new academic year, with no warning.

The DfE says that it acted on the emerging new evidence (i.e. the collapse of more structures due to RAAC) but again, this raises questions over the quality of advice that the DfE had been receiving up to that point. Why did it take more ceilings to collapse for the DfE to reassess the risk?

Funding matters

The issue of squeezed school budgets, including teacher pay, has been widely reported and debated. But coverage is rarely dedicated to the state of school buildings and the trends in capital funding for schools (that is, money allocated to schools for the creation of new places, maintenance, repairs and new rebuilding programmes).

The past few days has changed that, as more details and analysis has emerged about the trends in capital funding and how that has compared to need. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has published a more detailed analysis of capital funding, but the key reflection from this incident is the importance of heeding the evidence.

As the IFS analysis shows, overall capital funding has declined since 2010, largely as a result of the cancellation of the Building Schools for the Future programme that year.2 The annual average capital expenditure for the past three years (to 2023-24) is £5.2bn. This represents a 26 per cent real terms cut compared to the three-year average in the years up to 2008-09 and around a 50 per cent cut compared to expenditure in 2009-10. It should be noted, however, that capital spending rose significantly in the period between 2002-03 to 2009-10 (from a relatively low base of just over £4bn per year to a high of just over £10bn per year to fund the BSF programme).

The IFS also notes that spending hasn’t kept pace with cost, with funding for maintenance and repairs only increasing by 3 per cent in real terms since 2015-16 (whereas costs have risen much faster).

These trends are in direct contrast with what officials and independent bodies have recommended is actually needed to maintain and repair the school estate. According to the National Audit Office, the DfE recommended back in 2020 that £5.3bn per year was needed in order to “maintain schools and mitigate the most serious risks of building failure”, with £7bn per year representing best practice levels of funding. Instead, the DfE was awarded £3.1bn per year by the Treasury in the 2020 spending review.3

The NAO report also states that the DfE “has recognised the significant safety risk across the school estate – its corporate risk register shows as ‘critical and very likely’ the risk that building collapse or failure could cause death or injury.” and goes on to say that the “DfE considers that insufficient capital funding to address structural issues, and the condition of some buildings at the end of their initial design life, contribute to the severity of the risk.”

There have also been further reports by the former Permanent Secretary that, despite the DfE recommending that the school rebuilding programme should be expanded from 100 to 200 schools per year, it was instead cut to 50 schools per year.4

What do we currently know about the affected schools?

At present, there is no official published list of schools that are known to have RAAC but the DfE has committed to publishing a full list, with agreed mitigations, by the end of this week. In the meantime, the BBC has been collating a list of schools that have voluntarily come forward. So far, this totals 79 schools and the reported mitigation actions include moving pupils to other parts of the school estate or neighbouring schools, delaying the start of term for some or all pupils and moving some pupils to online learning.

We have run some initial analysis on those schools to explore whether there are any important patterns in relation to their locations, governance and pupil demographics. We share these now as preliminary analysis only which could change once the full set of schools is added to our analysis.

- So far, we have found that 13 of the 79 identified schools also had rebuilding works stopped under the Building Schools for the Future programme. If we look at secondary schools alone (as only secondary schools were eligible for the BSF programme), this equates to 1 in 3 schools having been both identified as having RAAC and having their BSF project cancelled. We have also cross-checked this against the list of schools that were approved for under both waves of the Priority Schools Building Programme and they did not receive funding under that programme either.

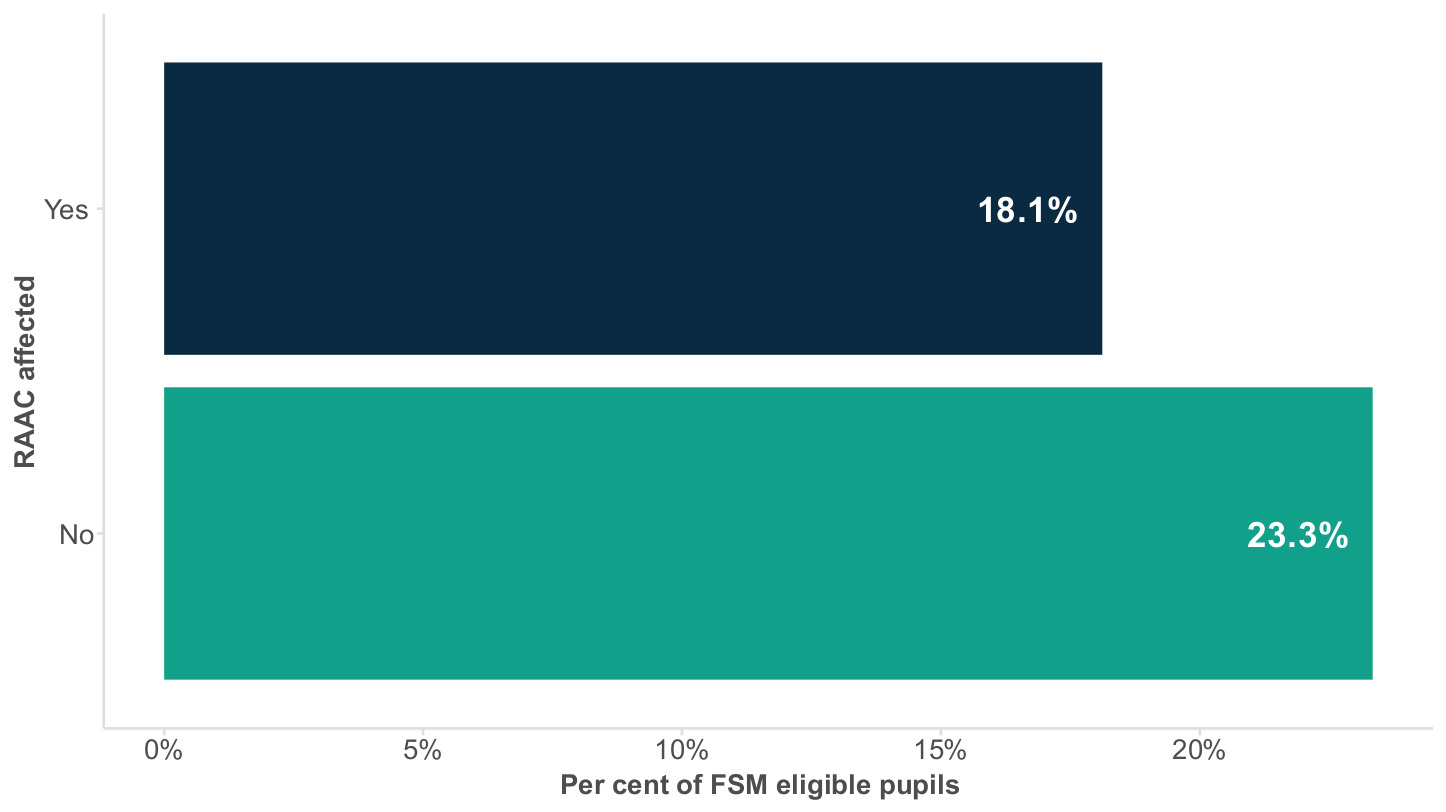

- We also looked at whether RAAC -affected schools had higher rates of disadvantaged pupils. We found no pattern so far (if anything, they have lower rates of disadvantaged pupils based on the schools in our dataset so far).

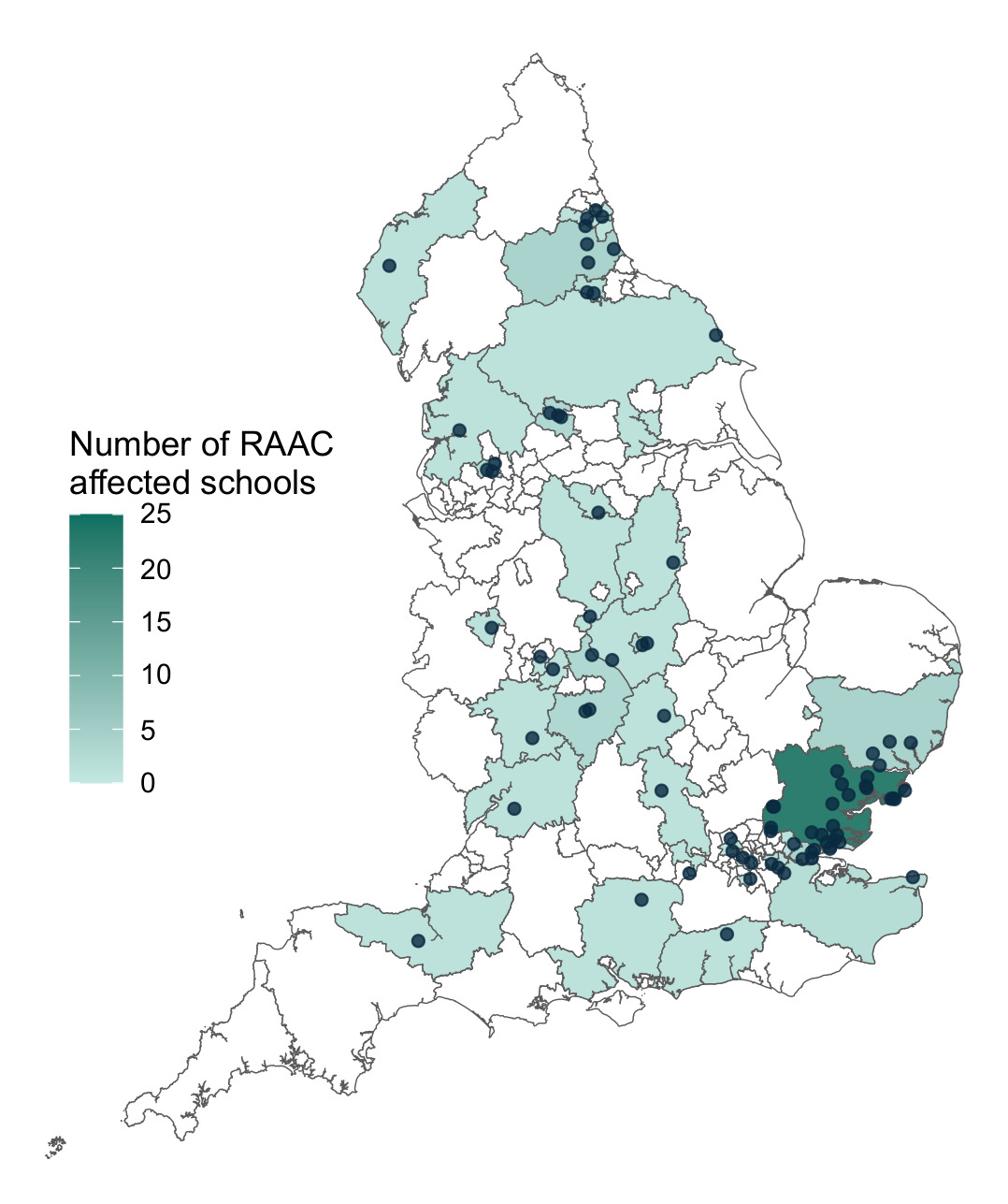

- Finally, we find no distinct regional trend. There is a relatively dense cluster in the South East because we know that Essex has already identified a large number of schools (around 50).

Reflections (so far)

The immediate reflection from what we know so far is the importance of forensic and timely risk management, particularly for an organisation as large as the DfE. The risk posed by RAAC came back on to the DfE’s radar in 2018, but it took a further four years for that to translate into proactive steps to identify schools affected. This raises important questions about what steps the DfE took back in 2018, and whether the Treasury received and assessed any bids for additional funding to address RAAC in schools.

The delay in further action is likely to have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, which would have diverted DfE’s resources and focus. Nevertheless, other “critical” risks, particularly those which pose a threat to public safety, should not have been overlooked.

Effective data collection is key to both managing the risk and taking action. At present, we are unable to estimate the level of disruption on schools, pupils and parents because there is a lack of information on the number of schools identified and the mitigation actions that have been or will be put in place. The delay in surveying schools also led to further structural collapses due to RAAC and an emergency response from the DfE. While there is no question that the DfE was right to prioritise pupil and staff safety, there are lessons to be learned in whether the collection of data and expert advice could have been better managed.

Complexities of governance and funding streams may also have contributed to a lack of transparency and, potentially, late identification of problems. The governance arrangement of a school, combined with the number of schools within its trust (where relevant), determines how it applies for funding. This means that, in some cases (such as with larger multi academy trusts), the DfE doesn’t have eyes on how capital is being allocated to or meeting the needs of individual schools within the trust (despite the DfE being ultimately responsible for these schools). It also means that there is not a consistent public record of schools that have applied for capital funding to address RAAC or other dangerous structural related issues.

Most starkly is the issue of missed warnings and opportunities to properly fund school buildings. Every government talks passionately about the importance of schools as places in the heart of communities, yet the warnings of the deteriorating and unsafe school estate (even posing a “threat to life”) have not been heeded.

The risks to school buildings do not relate solely to RAAC. The NAO estimate that around 38 per cent of school buildings are “beyond their estimated initial design life”.5 While this doesn’t equate to a critical threat in all cases, many are likely to require more maintenance funding and higher running costs. In any case, the need for the DfE to have a laser-light focus on the conditions of the school estate has never been greater.

The government now needs to ensure that affected schools have the resources they need to continue to serve their pupils. It has said that it will fund capital costs relating to the mitigation actions that RAAC affected schools will need to take, and it will also meet the costs of full remedial works. In the immediate term, there is a lack of clarity over whether it will fund non-capital costs associated such as transport to temporary sites or rental costs for temporary buildings. The DfE has said schools should discuss individual circumstances with their caseworker. In the longer term, it is unclear where the government will find additional money for the (at least) 156 RAAC affected schools. After ten years of real term budget cuts, it cannot expect schools to fit the bill, nor would it be palatable to raid the early years or post-16 budgets.

Questions must also be asked about how this state of disrepair in the school estate has been allowed to go on for so long and whether capital funding allocated to the Free Schools programme, for example, might have been better routed towards rebuilding and maintenance funding.

The government faces a tough set of choices and, sadly, the consequences of not intervening early enough. This latest incident uncomfortably follows the widespread disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic, from which we are still seeing an impact on lost learning and a widening of the gap between the most disadvantaged pupils and the rest. We cannot allow it to set back any recovery we hope to make.