In this blog we take a brief look at the GCSE attainment gap for children who are looked after by local authorities in England, alongside outcomes for the wider group of ‘children in need’.

Looked after children are cared for by their local authority for a period of at least 24 hours, for example in a children’s residential home or foster home, whilst children in need (CIN) are assessed as needing help and protection because of risks to their health or development. Some children in need are considered to be at risk of significant harm – for example, due to neglect, or physical, sexual or emotional abuse – so have a statutory child protection plan (CPP) drawn up by their local authority. It has been estimated that by age 16, one-quarter of all children will have fallen into one of these groups at some point. [1]

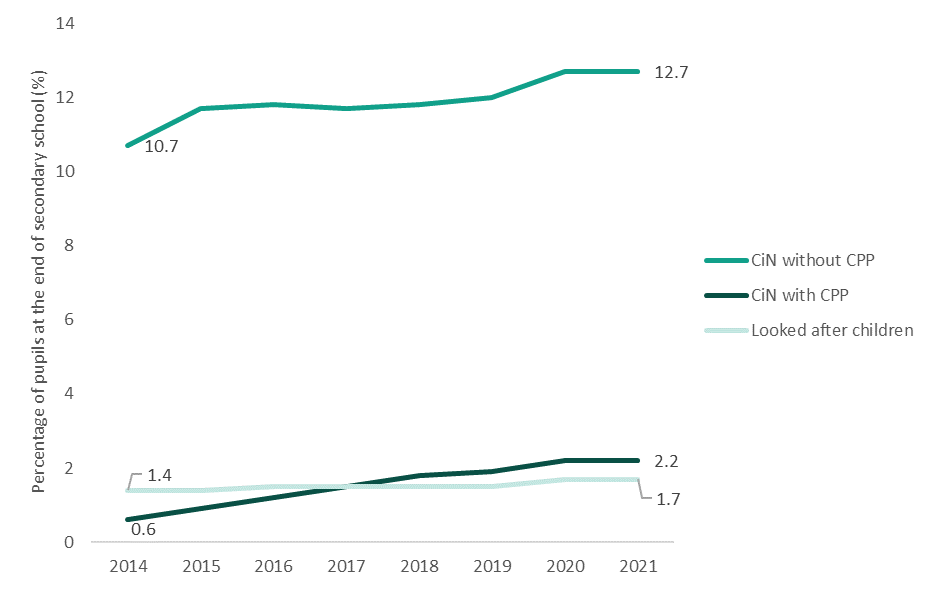

In this blog we distinguish between three (non-overlapping) groups: children who have been looked after in the previous six years; children in need with a CPP in the previous six years and children in need without a CPP in the previous six years. The latter is by far the biggest of the three children’s social care groups, representing 12.7 per cent of pupils at the end of secondary school in 2021 (compared to 2.2 per cent having a child protection plan and 1.7 per cent being looked after), though the size of each group has been growing in recent years (Figure 1). The number of children with a child protection plan in the previous six years has more than tripled in relative terms since 2014, overtaking the size of the looked after group.

This trend of rising numbers of children in children’s social care has been noted in several studies, with the NAO (2019) highlighting “significant increases” in the most serious cases.[2] These patterns are also not unique to England and have been broadly mirrored in Wales and Northern Ireland over the last decade, though not in Scotland (Department for Education, 2022).[3]

Figure 1: The proportion of pupils at the end of secondary school in key social care groups has been rising in recent years

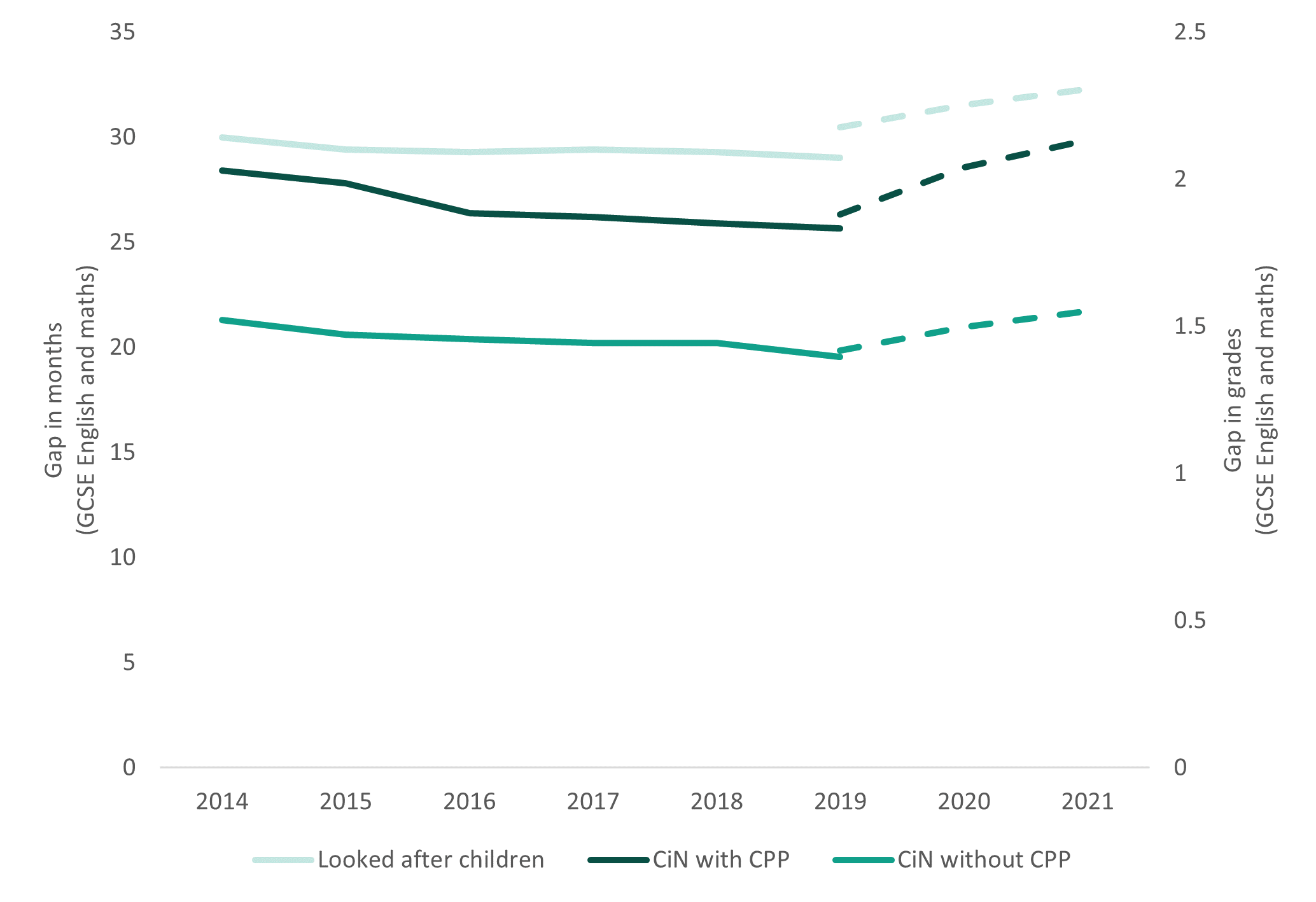

Pupils in all three social care groups have, unsurprisingly, worse GCSE attainment than their peers[4] (Figure 2). Prior to the pandemic in 2019, looked after children were almost 2.5 years (29 months) behind their peers across GCSE English and maths. To put this in perspective, this is somewhat smaller than the attainment gap for children with a special educational need or disability who have an EHCP (at 41 months) but larger than the gap for those receiving SEN support (at 2 years), whilst recognising that there is considerable overlap between these groups. [5]

The gap for children in need with a child protection plan was smaller but still very wide at 26 months in 2019, meanwhile for children in need without a plan, it was 20 months – larger than the gap for pupils eligible for free school meals at any point in the previous 6 years (18 months) but smaller than for those who are in long-term poverty (23 months). [6]

The gap for all three groups had been decreasing over the period 2014 to 2019, most notably for those with a CPP (by 10 per cent), with smaller reductions for children in need without a plan (8 per cent) and only marginal progress for the looked after group (3 per cent).

Figure 2: The GCSE attainment gap narrowed for key social care groups in the years prior to the pandemic but has since widened

However, looking at what has happened since the onset of the pandemic, it is clear that progress has gone into reverse. The gap widened markedly for all three groups in 2020 and each fell even further behind their peers in 2021. Although we measure the GCSE gap on a different basis during this pandemic period – necessitated by the fact that exams were cancelled and replaced with alternative, temporary arrangements for assessing grades – the (percentage) widening in the gap between 2019 and 2021 essentially wiped out the earlier progress that had been made up until 2019. And just as the gap for those with a child protection plan narrowed the most pre-pandemic, it subsequently widened the most post-pandemic.

It may seem obvious and inevitable that educational inequalities widened during the pandemic. However, it is worth saying that, initially, this wasn’t actually the case for (economically) disadvantaged children. Our research[7] found that, counter to widely held expectations at the time, disadvantaged children didn’t lose out relative to their peers in 2020, at least in terms of the GCSE grades they were awarded. The widespread increases to GCSE grades that occurred in 2020 under centre assessments benefited disadvantaged children just as much as their non-disadvantaged peers, on average, leaving the overall disadvantage gap unchanged.

Clearly this benign picture of GCSE grade increases being shared evenly across vulnerable groups in 2020 did not extend to those in social care (whose grades then subsequently fell even further behind their peers in 2021). [8] Our research also found that grade gaps widened for children with SEND and those with English as an additional language (EAL) in the aftermath of the pandemic.

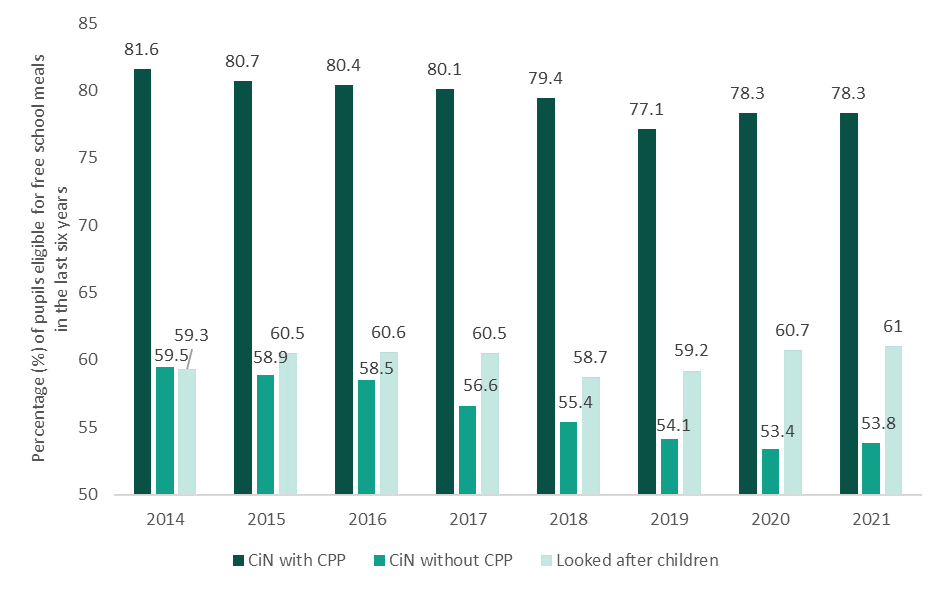

To better understand trends in the attainment gap, it is helpful to consider levels of socioeconomic disadvantage within these social care groups. All three have very high levels of disadvantage (Figure 3). This is most marked for children on a child protection plan: 78 per cent were eligible for free school meals in the last six years in 2021, compared to 61 per cent of looked after children, 54 per cent of children in need without a plan and just 19 per cent of their peers.

Figure 3: Changes in levels of disadvantage can only partly explain trends in the GCSE attainment gap

In the years leading up to the pandemic, there was a downward trend in levels of disadvantage among children in need and those on a child protection plan but no change for looked after children. This coincided with more children involved in social care over this period (as seen in Figure 1). These compositional shifts may partly explain the narrowing attainment gap for children in need and children with a child protection plan over the pre-pandemic period (meaning these groups were capturing a less disadvantaged set of pupils over time with higher attainment, on average) which was not replicated for looked after children.

Yet since 2019, levels of disadvantage have increased among children in need with a child protection plan and looked after children but have continued to fall slightly among children in need without a plan, whilst attainment gaps have risen for all three groups (as seen in Figure 2). This suggests that compositional effects are unlikely to be the full story and, put simply, children in social care have been left even more vulnerable in the wake of the pandemic.

There is growing evidence and recognition that disadvantaged children have been particularly affected by pandemic learning losses, with a recent Public Accounts Committee report stating that “disadvantaged pupils suffered most, wiping out a decade of progress in reducing the gap in attainment between them and their peers”.[9] But debates on education recovery should not lose sight of serious impacts for other vulnerable groups including children in social care and children with additional needs. The National Tutoring Programme remains the most high profile plank of the Department’s recovery programme. However, a much bigger and more versatile toolbox is needed to address the scale of education recovery. As we called for in EPI’s first recovery report[10], this needs to go beyond academic programmes and support children’s social and emotional learning – for example, funding schools to deliver mental health support – as well as urgently tackling child poverty. The importance of tackling poverty as part of wider reforms was highlighted by the independent review of children’s social care (MacAlister, 2022).[11] Without a serious plan with proper investment, some of the most vulnerable children in our society will continue to be let down.

References –

[1] https://osf.io/6ecrz/wiki/home/

[2] https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Pressures-on-Childrens-Social-Care.pdf

[3] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1080111/Drivers_of_Activity_in_Children_s_Social_Care.pdf

[4] We compare the attainment of these three groups with that of children who have been neither in need, looked after, or on a child protection plan at any point over the last six years.

[5] Children in need are nearly twice as likely to have SEN support as the overall pupil population: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/outcomes-for-children-in-need-including-children-looked-after-by-local-authorities-in-england/

[6] Defined as pupils eligible for free school meals for 80 per cent of their time in school.

[7] https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/disadvantage-gaps-in-england/

[8] In March 2023, DfE published ‘Outcomes for children in need, including children looked after’ for the 2021/22 academic year. Whilst it is not possible to replicate our months or grade gap measure using this data, using average Attainment 8 scores shows that the gap between key social care groups relative to the overall pupil population widened in 2022. https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/outcomes-for-children-in-need-including-children-looked-after-by-local-authorities-in-england/

[9] https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/40220/documents/196416/default/

[10] https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/education-recovery-and-resilience-in-england/

[11] This stated: “In the case of deprivation, we have now reached a point where the weight of evidence showing a contributory causal relationship between income, maltreatment and state intervention in family life is strong enough to warrant widespread acceptance”, p10. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20230308122310/https://childrenssocialcare.independent-review.uk/review-background/